|

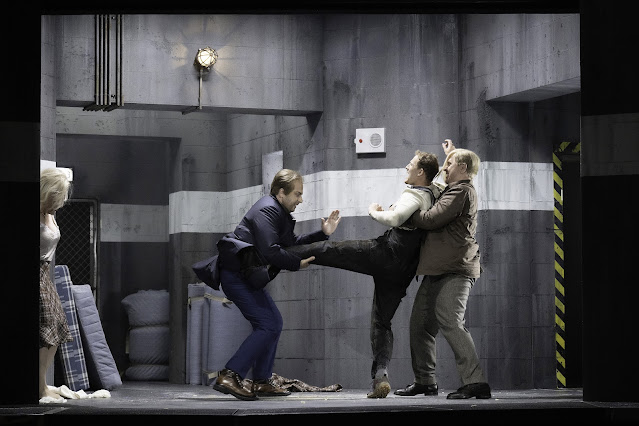

| Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto – Robert Raso (Curio), Lucile Richardot (Cornelia), Yuriy Mynenko (Tolomeo), Andrey Zhilikhovsky (Achilla) – Salzburg Festival (Photo: SF/Monika Rittershaus) |

Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto: Christophe Dumaux, Olga Kulchynska, Lucile Richardot, Federico Fiorio, Yuriy Mynenko, Andrey Zhilikhovsky, director: Dmitri Tcherniakov, Le Concert d’Astrée, Emmanuelle Haïm; Salzburg Festival at Haus für Mozart

Reviewed 14 August 2025

Despite Dmitri Tcherniakov’s updating of the drama, there was something weirdly compelling about the performance. The cast really convinced you that these people mattered, that we needed to watch their drama.

Asking Dmitri Tcherniakov to direct Handel’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto, the director’s first Baroque opera, was never going to produce a straightforward piece of music theatre. But that is what festivals are for, to push boundaries and to create events not possible in the regular theatrical mill. Salzburg Festival did just that, and Tcherniakov’s take on Handelian Opera Seria is a big feature of this year’s festival.

I caught the penultimate performance of Handel’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto on 14 August 2025 at the Haus für Mozart as part of the Salzburg Festival. Dmitri Tcherniakov directed and designed the sets, with costumes by Elena Zaytseva, and Emmanuelle Haïm conducted Le Concert d’Astrée. Christophe Dumaux was Cesare with Olga Kulchynska as Cleopatra, Lucile Richardot as Cornelia, Federico Fiorio as Sesti, Yuriy Mynenko as Tolomeo, and Andrey Zhilikhovsky as Achilla.

In an interview in the programme book Tcherniakov commented that ‘At first, it [Baroque Opera] left me baffled’, going on to add, ‘how to make the characters feel alive when all I have were about forty exquisite arias – and little else’.

His solution was to place the action in the present, after an apocalyptic event. The evening began with warning sirens and the events unfolded in a nuclear bunker. The chorus (sung by Bachchor Salzburg) was an invisible presence, singing from the balcony and playing no part in the stage action, leading you to wonder, did they even exist in Tcherniakov’s revised scenario.

His fixed set presented three areas, one colonised by Cesare and Curio, another by Cornelia and Sesto and a third by the Egyptians. For much of Act One, the entire cast was present all the time, gone was the concept of the Exit Aria. At times it felt like Tcherniakov had been watching too many Katie Mitchell productions; he gave us two other visual contexts to compete with the main aria. For instance, towards the end of Act One, this meant Lucile Richardot’s Cornelia and Federico Fiorio’s Sesto having to compete with Christophe Dumaux (Cesare) stripping down to his underpants before retiring to bed!

What this did was enable Tcherniakov to recontextualise arias by having different characters present and reacting to the singer, thus creating a more complex web of inference and influence. When Olga Kulchynska’s Cleopatra told Yuriy Mynenko’s Tolomeo about the Roman’s reception of Pompeo’s head (here his full body), Tolomeo already knew this but Tcherniakov made it clear this was all part of the siblings’ games with each other. Two lesser-known arias for Cesare and Cleopatra in Act One acted as an extension of their wooing. This recontextualisation got more problematic in Act Two when Yuriy Mynenko’s Tolomeo ordered the arrest of Cornelia and Sesto, with Cornelia to be put into the harem, though by this point in the opera we had come to suspect that Yuriy Mynenko’s Tolomeo may have been somewhat delusional.

The perspicacious amongst you will have realised that with this scenario Dmitri Tcherniakov rather dug himself into a hold when it came to Act Three.

Though Dumaux’s Cesare survived the assassination attempt, it was in fact a shooting by Curio (Robert Raso) and Act Three did not open by the sea side. Cesare’s song to the breezes, magically sung by Dumaux, was presented as a hallucination, presumably due to illness. For the rest of the act, Tcherniakov used every trick in the Regieoper Handbook to avoid Handel and Haym’s dramaturgy. For Tcherniakov’s characters there was no happy end, no resolution. They were trapped in a Lord-of-the-Flies-like hellscape in their bunker. Every positive aria in the last act was presented as an example of the character’s delusion or mental fragility.

The production, however, did use one coup de theatre that was pure theatrical magical and almost worth the visit alone. Just before the scene when Cleopatra seduces Cesare by singing ‘V’adoro pupille’ there was an explosion. When the lights came back on,the nine orchestral musicians playing the nine solo lines (for the nine music in the original scene) were placed above the main set (alas no photograph). No, I have no idea how this impacted Tcherniakov’s neo-realistic presentation but it created a piece of pure musical and theatrical magic.

All the male characters were played by men with a preponderance of male falsettists. This concentration on a single voice type was something Handel never did. For reasons of, I suspect, a mix of economics and personal preference, he always used a mix of voice types, typically soprano, mezzo-soprano, contralto, castrato.

|

| Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto – Olga Kulchynska (Cleopatra), Jake Ingbar (Nireno) Salzburg Festival (Photo: SF/Monika Rittershaus) |

We last saw Christophe Dumaux as Cesare in 2011 at Versailles [see my review

on Music & Vision]. 14 years later Dumaux was more the middle-aged

politician than action hero, a man of wheeling and dealing. But he sang

with fine virile tone that brought alive both ‘Va tacito’ (the aria with

horn obbligato) and his Act Two call to arms. His voice was lithe and

focused, giving a crisp vividness to his passage-work. However the

carrying power was not complemented by amplitude and at times you felt

this Cesare was using his voice as a weapon. His scenes with Olga

Kulchynska’s Cleopatra were charming but this was no great love affair,

it was two lonely people coming together.

Olga Kulchynska made a dazzling Cleopatra, from her first entrance wearing a pink wig and tight leather trousers. Sulky and as much a poseur at first, as she jockeyed with her brother, she charmed Dumaux’s Cesare and developed real depth of character. In Act Two, ‘V’adoro pupille’ allowed her to make Handel’s magic really work. She had a light bright tone, superbly accurate too, yet she was fully equal to her two big serious numbers, ‘Per pieta’ and ‘Piangero’. We entirely forgot Tcherniakov’s revised dramaturgy and were captivated. Even her final aria, sung hardly in triumph but in delusion, was magic.

Lucile Richardot’s Cornelia looked and behaved so like actress Gillian Anderson that I wondered whether Tcherniakov’s intentions extended to pop culture references that I missed. She presented Cornelia as a woman concerned with image, yet Richardot sang with richly focused power and a Handelian intensity. There was a depth to her tone that entirely re-balanced the character. And in Cornelia’s interactions with Yuriy Mynenko’s Tolomeo, Richardot conveyed powerfully the way the character had her self-image stripped away. After Tolomeo’s death, Richardot made Cornelia’s final actions a sad attempt at recapturing her original image. There was one strange, somewhat false note in the depiction of Cornelia’s relationship with her son when, during a particularly intense moment in Act Two, Tcherniakov introduced a suggestion of incest.

Federico Fiorio was an astonishing Sesto. Hyperactive from the beginning and almost certainly intended to be on the spectrum, Fiorio used physical movement as much as musical expression to project Sesto’s uncertain character, including two striking bouts of physical expression, hardly dance, during instrumental interludes. Sesto is meant to be young, probably a teenager constantly psyching himself up to do a deed too great for him. An adult Sesto creates dramatic problems and Tcherniakov’s solution was a neat one. Fiorio satisfied musically, bringing a lithe accuracy and tenderness to the role. It sits high for the male falsettist and there were times when felt a woman might have brought a wider range of tone colour. Yet this worked with Fiorio’s portrayal of Sesto as damaged.

|

| Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto – Lucile Richardot (Cornelia), Andrey Zhilikhovsky (Achilla), Federico Fiorio (Sesto), Yuriy Mynenko (Tolomeo) – Salzburg Festival (Photo: SF/Monika Rittershaus) |

Yuriy Mynenko was a wonderfully deluded, self-regarding Tolomeo complete with impractical yet very stylish asymmetric haircut. Mynenko did sulky well; he and Kulchynska had a terrific line in sibling taunting. Mynenko’s Tolomeo was vicious, yet also deluded. The production occasionally required you to ignore some of the libretto, to make the dramaturgy work and I was never sure whether this was true of Tolomeo or not, whether he lived in his own little world.

Andrey Zhilikhovsky’s Achilla was a nasty piece of goods partly

because he was clearly so intelligent and largely seemed to

control Mynenko’s Tolomeo. Zhilikhovsky delivered his arias admirably,

never making them feel the make-weights that they can be. Jake Ingbar

was a nicely two-faced Nireno, changing sides and always on the look out

for the main chance. His Act Two aria, another potential make-weight,

was here nicely used to draw Cesare further into Cleopatra’s orbit.

Robert Raso (on the festival’s Young Singers Project) was an entirely

admirable Curio. He didn’t get that much to sing but played a huge role

dramatically. There was one extra cast member. The actor Rene Keller as

the dead Pompeo whose body underwent rather a log of lugging around and

which, by the end of the opera, must have been smelling to high heaven!

|

| Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto – Federico Fiorio (Sesto) Salzburg Festival (Photo: SF/Monika Rittershaus) |

Baroque opera was very fond of the three unities, so operas often consist of a group of characters spending three acts together in the same place. What I think of as the locked room scenario; Handel’s Tamerlano is like this. Giulio Cesare is not; one of the reasons for its modern revival is that it does have a linear plot. The irony of Dmitri Tcherniakov’s production was that he chose to solve the work’s problems (as he saw them) by turning it literally into a locked room drama. I disliked the way he rewrote the dramaturgy and with the production’s neo-realistic style, it was fatally easy to pick holes in this revised scenario. In the programme book he says he dislikes happy ends, he takes a depressive view of the human condition. In that case, why Giulio Cesare, why not an opera like Tamerlano that lends itself more to this type of interpretation?

But that said, Dmitri Tcherniakov is a theatrical magician and there was something weirdly compelling about the performance. The cast really convinced you that these people mattered, that we needed to watch their drama. Which is saying something for a Baroque opera series, a genre often derided as frivolous

This was a large-scale performance with the orchestra fielding over 40 players with a continuo team of seven. The results fill the theatre with colour and movement. Emmanuelle Haïm kept speeds fluid and the work had constant impetus with no awkward pauses. It helped that her singers all had a neat way with passagework so the music never felt driven.

I am not sure this was a Giulio Cesare for the ages and certainly it was a long way from Janet Baker, Valerie Masterson, John Copley and Charles Mackerras who were responsible for the first performance of the opera that I ever saw back in the 1980s. But any great work of art can take a wide variety of interpretations.

This if the first of five reviews from this year’s Salzburg Festival and I would like to thank the festival for their help in organising my visit.

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Going where no other company has dared: Green Opera gives the stage premiere of Joubert’s Jane Eyre at Grimeborn Festival – opera review

- New challenge & new repertoire: trumpeter Matilda Lloyd her new disc, Fantasia, pairing contemporary pieces with Baroque – interview

- I Shall Hear In Heaven: Tama Matheson impressively incarnates Beethoven with music alongside the spoken word – music theatre review

- BBC Proms: Classics, bon-bons & an engagingly fresh account of a masterpiece, Nil Venditti conducts BBC NOW – concert review

- Bayreuth Festival: Thorliefur Örn Arnarsson’s interpretation of Tristan und Isolde is a well-planned and thoughtful affair – opera review

- All-consuming: Kateřina Kněžíková’s account of the title role lights up Damiano Michieletto’s overly conceptual production of Janáček’s Káťa Kabanová at Glyndebourne – opera review

- BBC Proms – Arvo Pärt at 90: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Tõnu Kaljuste – concert review

- Baltic Tides: piano music by two important Baltic pianist composers, Lūcija Garūta & Ester Mägi makes for a marvellous, compelling disc – record review

- Frederick and his sister: music for Postsdam and Bayreuth created for Frederick the Great and Wilhelmine of Bayreuth – record review

- Passion project that deserves to be enjoyed: Alastair Penman’s The Last Tree – record review

- Home