|

| Jakob Lehmann (Photo: Sercan Sevindik) |

As the Orchestra Révolutionnaire et Romantique makes its first foray into Rossini, we talk to conductor Jakob Lehmann about his passion for music of the period, how we need to learn to enjoy energy, freedom and rubato in the music, his discoveries about balance in the bass line, working with modern orchestras and much more.

On 2 October 2025, conductor Jakob Lehmann joins the Monteverdi Choir and the Orchestra Révolutionnaire et Romantique at Cadogan Hall for Rossini’s Stabat Mater alongside excerpts from his opera Ermione. This will be the orchestra’s first foray into Rossini and the inaugural event in a planned major new exploration of Rossini’s music. Jakob was Associate Artistic Director of New York-based opera company Teatro Nuovo from 2019 to 2025 and is Artistic Director of Eroica Berlin, a chamber orchestra he founded in 2015.

Jakob’s recent experience includes conducting Les Siècles in Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony at the International Bruckner Festival in Linz for the composer’s 200th anniversary celebrations, as well as performances of operas by Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi. When we spoke, Jakob was in Bloomington, Indiana and about to make his debut with Indiana University Concert Orchestra. The Cadogan Hall concert will be his London debut, whilst his UK debut was last month when he conducted the Scottish Chamber Orchestra in Rossini, Spohr and Schubert.

Historically informed performances (HIP) of Rossini’s music in London have still been relatively rare, and I was interested in finding out what Jakob thought HIP brought to the composer. His thoughts were two-pronged. First, the added colours and textures of the period instruments allow a different type of storytelling through the new sound qualities. This is especially true of Rossini. Jakob feels that, unlike composers such as Mozart and Beethoven, with Rossini, we have not fully grasped the sound and style of period Rossini; we have not fundamentally absorbed the style change that has happened in other composers.

|

| Jakob Lehmann & Anima Eterna Brugge (Photo: Koen Broos) |

The other side effect of HIP is that we come to appreciate the sheer quality of the music in another way. As an example, Jakob mentions the Berlin Philharmonic, which, 30 years ago, would not have dreamed of doing an evening of music by Telemann or Vivaldi, but they do now, thanks to extensive period performances. We have a different view on the value and quality of the music. This is something that has not happened in Rossini, yet. Jakob feels that we still underestimate the composer. He was not just writing for singers, and we should appreciate how he writes for the orchestra.

Jakob points out that performing with period instruments is one thing, but historically informed performance practice is another, and we still have more to discover about performances of Rossini’s era. HIP originally jumped back in time and looked at music from a particular point of view. Now, for different eras, we can juxtapose early recordings, writings of early commentators and notations on surviving parts.

Jakob feels that we need to learn to appreciate the rhetoric needed in the music and enjoy Romantic melodies. He mentions an article, ‘Why has early music become so crisp’, and he feels that in Rossini and other bel canto music, we need to enjoy the energy but also the freedom and rubato, the ability to follow a bel canto line. If you add in the sound of the period instruments, you get a new picture.

Talking to Jakob about Rossini, you feel that he is passionately evangelical about the composer. For him, Rossini is a great composer, and he is motivated to show how fantastic Rossini is.

|

| Isabella Colbran who sang the title role in Rossini’s Ermione in 1819 |

In the forthcoming concert, he and the orchestra are aiming to show the two sides to the composer, sacred and secular, with a varied and interesting programme. It was decided quite early on that the concert would be a mix, and because the Monteverdi Choir would be involved, they wanted a big choral piece to provide ample opportunity for the choir. They are performing Rossini’s Stabat Mater, which was written between 1831 and 1841 and premiered in Paris in 1842. Alongside this, they are performing substantial excerpts from his opera Ermione, written for Naples in 1819, where Rossini was using classical forms and expanding them.

The concert is intended to launch a long-term collaboration between the orchestra and Jakob, so this first programme is also intended to show what is in store, to give an impression of the repertoire Jakob will be looking at and how they will present it. They are performing whole scenes from the opera, thus celebrating the launch of a long-term series where, in future, they hope for complete performances of the operas.

As far as Jakob is concerned, Rossini’s best work is in his serious operas, particularly those written for Naples between 1815 and 1822. Jakob describes the subject matter of Ermione as being womanhood. Andromaca (Andromache), the widow of Hector, is trying to save her son, and Jakob sees her as the only winner. She is the only one of the protagonists that the audience can like, and the only one who gets what she wants, as all the others are destroyed by ambition and passion. It is also a strongly choral piece, with the chorus used to effect in the overture. This choral aspect and the general subject of motherhood are the links between the two works in the concert, Ermione and the Stabat Mater. The Stabat Mater was written much later than Ermione, after Rossini had retired from the theatre. Jakob says that the work still sounds like Rossini, but you can hear how he has progressed as a composer.

Jakob is as passionate about voices as about instruments. But he points out that singing is different to instrumental performance. A singer’s technique is embodied in the body, and you cannot change their style the way instrumentalists can change their performance. What Jakob has done is find singers who can bring the gifts needed in the music. With HIP, the instruments enable the singers to look for freedom, colour and flexibility.

Listening to early recordings of singers and reading the writings of the pedagogue Manuel Garcia (1805-1906), who was the brother of the singers Maria Malibran and Pauline Viardot, informs Jakob’s choice of voices. He does not go for an Early Music sound in the music, but operatic and full-bodied singing. The tools that the singers of the period had were rooted in bel canto with flexibility, a fast open vibrato, use of legato and portamento as an expressive device, along with the clarity of text. Also, with sopranos and mezzo-sopranos, the use of both registers, including the chest, is part of the style.

Finding the right singers means looking for those with an ability to be flexible, a willingness to experiment and a curiosity to find out what they can do. This also means finding appropriate ornaments in the music. Composers expected music to be ornamented, and we have examples of Rossini doing this. But to find period-appropriate ornamentation takes study, along with a willingness for the singers to do things differently than a standard performance of Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia. Jakob describes his singers for the performance as being very curious, open and flexible, and he is excited to be able to experiment with them.

|

| Rossini in 1850 |

Jakob’s work in bel canto and 19th-century Romantic music links to his own personal liking for the music of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He had an ear-opening experience when he first heard the Orchestra Révolutionnaire et Romantique in the overture to Weber’s Oberon, when he found the sound world incredible. This drew him into the Period world. Early on in his career, he was lucky to be the concertmaster of Anima Eterna Brugge, an ensemble that was playing a lot of 19th-century music. They were experimenting to find the right style and instruments, with many late-night conversations about such topics as the fingerings in Spohr. This led him to be curious about finding new things and new challenges.

He was lucky to work with musicologist Clive Brown and conductor Will Crutchfield, who founded Teatro Nuovo, the American opera company and training institution specialising in the repertory and performance practice of bel canto opera. Jakob has just finished as Associate Artistic Director with Teatro Novo, and he appreciates the company’s combination of young singers and instrumentalists with fundamental research in style.

One of Jakob’s big discoveries from working with Teatro Nuovo was the realisation of the nature of the balance in the bass line in Italian orchestras of the time. Orchestras always had more double basses than cellos (something that does not happen in modern orchestras), such as two cellos and six basses. At La Scala, they had 12 double basses and eight cellos. Also, the double basses were three-stringed instruments (modern ones have four or five strings). This means that the instruments are very resonant because of the lower tension of the thicker gut strings. The result is what Jakob refers to as an incredible bass sound. They tried it out at Teatro Nuovo and at Cadogan Hall, Orchestra Révolutionnaire et Romantique will be using lots of double basses, three-stringed ones. And Jakob hopes that everyone experiences the music the way he did. The different balance in the bass line has implications for the way Italian composers wrote for the orchestra, and Jakob sees it as changing the music a lot. He feels that the discovery is well worth exploring and sharing with an audience.

Jakob comes from a musical family; his father played the trombone in the Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin. Young Jakob started learning the piano at the age of four and the violin at the age of seven. He was taken to concerts, music was there, and he became passionate about it at a young age. He was lucky that his teacher in high school nurtured his interest in period performance, encouraging him to try out gut strings and a period bow. He became interested – enjoying research, looking at manuscripts and playing from facsimiles. It was a way of approaching music that he found fascinating. It was a jump-in as concertmaster with Anima Eterna Brugge that helped launch his journey.

But Jakob is not just involved in period instrument performance. He does equal amounts of work with period instruments and modern ones. He jokingly comments that period instruments are not ‘the one truth!’ More than having the right instruments, he feels that the most important thing is having the right mindset. He feels there is sope for improvement and more research in period instrument groups that move between eras yet keep something of their house style. He feels that you can achieve much in the way of historically informed performance with modern orchestras that are open to this now, and he appreciates the way modern orchestras are flexible in this respect. He also appreciates the logistical aspect of working with modern orchestras. Coming to them as a conductor is fantastic, as everything is in place and set up.

|

| Jakob Lehmann (Photo: Pauline Cluzeau) |

From 31 October, Jakob will be conducting Les Siècles, the orchestra with whom he performed Bruckner last year, in Berlioz’s La damnation de Faust in a staging at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris, directed and designed by Silvia Costa with Benjamin Bernheim as Faust [further details]. During November, he will also be conducting Symfonieorkest Vlanderen in a programme that includes Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin and Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 [further details].

Further ahead, he is working with the Swiss ensemble, La Banda storica Bern, where members of the Bern Symphony Orchestra play on period instruments. During February, March, April and May 2026, Jaokob will be conducting modern instrument orchestras in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor in a production by Simon Delétang, which tours to French opera houses from Rennes to Compiègne. He will also be returning to Les Siècles to conduct them in a programme of music by Liszt and Wagner.

He describes his work as a mixture of period and modern, of opera and symphonic, the one lives off the other, and there are no dividing lines.

|

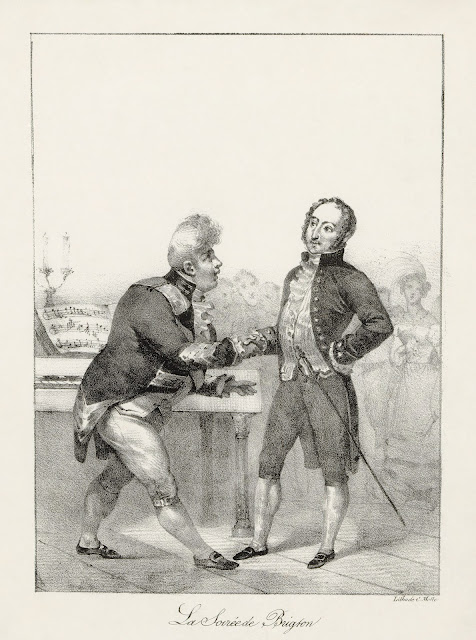

| Charles Motte: George IV greeting Rossini at the Brighton Pavilion, 1823 |

2 October 2025: Cadogan Hall

Rossini: Scenes from Ermione

Rossini Stabat Mater

Monteverdi Choir

Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique

Jakob Lehmann: Conductor

Thomas Guthrie: Stage Director

Soloists: Stabat Mater

Ana Maria Labin: Soprano

Hannah Ludwig: Mezzo-soprano

Alasdair Kent: Tenor

Anthony Robin Schneider: Bass

Ermione

Beth Taylor: Ermione

Hannah Ludwig: Andromaca

Alasdair Kent: Oreste

Anthony Robin Schneider: Fenicio

Rebecca Leggett: Cefisa

Elinor Rolfe Johnson: Cleone

Xavier Hetherington: Pilade

Marcus Swietlicki: Attalo

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Style, enthusiasm & scholarship: Ian Page and The Mozartists explore Opera in 1775 – opera review

- And there was dancing: Wild Arts immersive performance of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin at Charterhouse – opera review

- Colour and movement: Clarinet concertos from Peter Cigleris and Györ Symphonic Band – record review

- Johann Joseph Abert: A musical portrait – record review

- Profound, contemplative & meditative aethereal beauties: Vox Clamantis & Jaan-Eik Tulve’s birthday present for Arvo Pärt on ECM – record review

- Sung poetry: soprano Véronique Gens in subtle & supple form with pianist James Baillieu in French song at Wigmore Hall – concert review

- Two of the greatest concertos of the 21st century: Julian Bliss on recording Clarinet Concertos by Magnus Lindberg & Kalevi Aho – interview

- A restless soul: Matthias Goerne & David Fray in late Schubert – review

- Home