|

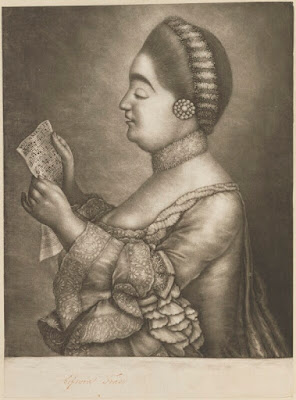

| Giulia Frasi who sang the three soprano roles in the premiere of Handel’s Solomon |

Handel: Solomon; Helen Charlston, Nardus Williams, Hugo Hymas, Florian Störtz, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Choir of the Enlightenment, John Butt; Queen Elizabeth Hall

Reviewed 12 October 2025

The OAE begins its 40th anniversary celebrations with the rich textures of Handel’s lavish oratorio giving us a feeling of profound satisfaction as one glorious event followed another.

The alarums and excursions associated with the 1745 Jacobite Rebellio, when the Jacobite army reached Derby, had a significant effect on the question of what sort of dramatic work an oratorio was supposed to be. Handel followed his pre-rebellion sequence of dramatic oratorios ending with Belshazzar in March 1745 with four military oratorios. Some, like the Occasional Oratorio were deliberately attuned to unstable times whilst Judas Maccabaeus had wider success. After Alexander Balus in 1748, where the military victories of the first half of the work are followed by personal tragedy, Handel seems to have set himself the challenge of returning to the question of what exactly was an oratorio.

What followed in 1749 was Susanna, a mix of pastoral comedy and moral tale, and Solomon, a plotless exploration of a sort of golden age rule, then in 1750 came Theodora, based on a romantic novel and much closer to what we might consider opera, then Jephtha in 1752 where the return of Handel’s favourite tenor, John Beard led to the creation of a remarkable anti-hero.

Similarly the forces Handel uses in these works varies in a way that suggests deliberate choice rather than economic necessity. Solomon is perhaps one of Handel’s most lavish with its double choruses and one of the largest orchestras Handel wrote for – flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets and drums.

It was Handel’s Solomon in all its celebratory richness that the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment chose to open its 2025/26 season, celebrating the orchestra’s 40th anniversary. John Butt conducted at Southbank Centre‘s Queen Elizabeth Hall on 12 October 2025. Helen Charlston was Solomon with Nardus Williams as Solomon’s Queen, First Woman, and the Queen of Sheba, Hugo Hymas as Zadok and Florian Störtz as A Levite.

John Butt contributed a fascinating article in the programme book looking at the way Solomon may have been Handel’s vision of an ideal state. The casting reflected Handel’s own with a female mezzo-soprano as the hero Solomon and a single soprano playing all three main female roles. The chorus was divided into two choirs of sixteen each, placed either side of the stage thus highlighting the antiphonal effects that Handel uses in some of the grander double choruses, though occasional instability of ensemble suggested why this layout is not always used.

But this is a choral work par excellence, with Handel demonstrating his sheer virtuosity in creating memorable textures. Act One began with the vigour and strength of the opening chorus ‘Your harps and cymbals’ where the separation of the two choirs was used to thrilling effect, but then in ‘With pious heart’ we had suave beauty of tone, and the act ended with the Nightingale Chorus that combined fine flute playing with an admirable lightness of touch from the singers. Act Two opened with the disciplined vigour of ‘From the censer curling rise’ with the glorious noise of the added trumpets, horns and drums. And this act ended with the dancing exuberance of ‘Swell, swell the full chorus’. In Act Three, Handel demonstrates his virtuosity by interleaving Solomon’s solo line with a sequence of choruses hymning the power of music. The ending of the work includes the stately grandeur of ‘Praise the Lord’, again with everyone making a glorious noise, and finally ‘The name of the wicked’, here eager and urgent with John Butt encouraging the two choruses to differentiate their contributions.

The role of Solomon is more of an exemplar than a real character. Helen Charlston embodied him with nobility and a smiling grace, exuding a quiet sense of satisfaction at his achievements. A big virtue of her performance was the way she made every word count, particularly in the recitatives which became something more than mere connective tissue. Her opening accompagnato, ‘Almighty Power’ displayed her virtues, the firm line, strong shape to the music and admirable words all supported by fabulous orchestral textures, then in ‘What though I trace’ she added some stylish ornaments into the mix. In Act Two, her aria ‘When the sun o’er yonder hills’ was full of the character’s inner confidence, then her final aria in Act Three ‘How green our fertile pastures look’ had an engaging catchiness too it along with some fine virtuosity.

But it is in Solomon’s relationships with his women that the interest in the work lies. Nardus Williams portrayed the three with style, grace, and discreet poise but I felt that she did not sufficiently revel in the virtuosity required to present three very different characters. She could have varied her tone more so that the Queen of Sheba had a greater sense of dignified power. As Solomon’s Queen, Williams moved from engaging joy in ‘Bless’d the day’ to strong articulation and rhythmic bounce in her duet with Charlston, ‘Welcome as the dawn of day’ then the touching lyric beauty of the queen’s final solo, ‘With thee th’unshelter’d moor’.

In Act Two Williams was First Woman with Angharad Rowlands as Second Woman. The two are first introduced in the trio, ‘Words are weak’. A terrific piece, here Williams was expressive yet firm contrasting with Rowlands admirably trenchant performance, alongside Charlston’s strong line. Williams’ aria, ‘Can I see my infant gor’d’ was plangent and moving, whilst she brought lyrical beauty to the First Woman’s final aria, ‘Beneath the vine’.

In Act Three, Williams’ account of the Queen of Sheba’s first aria, ‘Ev’ry sight these eyes behold’ was poised and engaging but lacked the sheer power to match the opening sinfonia. Her touching yet serious account of ‘Will the sun forget to streak’ was complemented by superb playing from the flutes and oboe, whose melody is frankly more memorable than the vocal line. The final duet for Williams and Charlston, ‘Ev’ry joy that wisdom knows’ proved to be remarkably perky!

The first Zadok, Thomas Lowe was known for the lyric beauty of his voice rather than any dramatic perspicacity and if you are not careful the character can be something of a prosy bore, popping up in each act. Hugo Hymas sang with an admirable sense of commitment to word, making his contributions count. And yes, giving us lyrical beauty too. ‘Sacred raptures’ in Act One featured some terrific runs, whilst he really did make the prosy ‘See the tall palm’ in Act Two seem interesting, whilst exuding a lovely confidence in ‘Golden columns’ in Act Three.

The Levite is a similarly redundant character, serving simply to comment. Florian Störtz was firm and solid in Act One, admirably believable whilst in Act Two he brought out a sense of exuberant joy and fine style in Act Three. The final soloist was Ilya Aksionov’s firm voiced messenger in Act Two.

Whilst the bigger choruses had the additions of two horns, two trumpets and timpani, the smaller and sometimes more intimate numbers all had plenty of instrumental beauty. I loved the way the two flutes blended their tone with the oboe’s in ‘Will the sun forget to streak’ and of course the two flutes were showcased on their own in the Nightingale Chorus. Whilst the Act Three sinfonia featured some wonderfully busy and buzzy oboe playing, the two were able to demonstrate sophistication elsewhere. There were a few numbers in the work where Handel let his bassoons off the leash and allowed them to create some gloriously rich orchestral textures. But even with just string, where was a rich variety and they were supported by two harpsichords (John Butt and Steven Devine) along with organ (Stephen Farr).

This is one of those works where seemingly nothing happens. Yet in this performance we derived an immense feeling of satisfaction as the performers made us really feel in the moment, as one glorious event followed another.

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Letter from Florida: Stéphane Denève conducts Beethoven’s Eroica – concert review

- Speaking the language of the past: Patrick Ayrton on Astrophil & Stella inspired by the world of English 17th-century composers – interview

- Engagingly modern: Rossini’s Cinderella at ENO is given a modern updating by Julia Burbach – opera review

- No easy options: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir & Tallinn Chamber Orchestra celebrate Arvo Pärt at 90 at Barbican – concert review

- Dresden-born composer, Sven Helbig’s Requiem A marks the 80th anniversary of the ending of World War II – concert review

- Political resonances & sheer poetry: English Touring Opera on strong form in Britten’s The Rape of Lucretia – opera review

- Sara Cortolezzis makes her debut at Covent Garden in Verdi’s Les vêpres siciliennes conducted by Speranza Scappucci – opera review

- Reformation: Mishka Rushdie Momen on mixing Renaissance piano music with later periods at the London Piano Festival – interview

- Strong emotions, vocal virtuosity : Rossini’s Ermione & Stabat Mater with Jakob Lehmann & Orchestra Révolutionnaire et Romantique – concert review

- Home