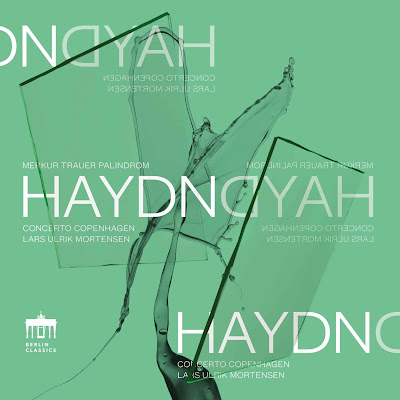

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 43 in E flat major ‘Mercury’, Symphony No. 44 in E minor, ‘Trauer’, Symphony no. 47 in G major, ‘Palindrome’; Concerto Copenhagen, Lars Ulrik Mortensen; Berlin Classics

Reviewed 22 October 2024

Small forces, big effects in these compelling performances of three Haydn symphonies from the early 1770s where the attention to detail and sheer energy really count

This disc Haydndyah from Lars Ulrik Mortensen and Concerto Copenhagen on Berlin Classics transports us to Esterhaza in the early 1770s and Haydn’s long Summers marooned at Prince Nikolaus Esterházy’s Summer palace. From 1766 onwards, the Prince and his court migrated from Eisenstadt to Eszterháza each Summer to inhabit the huge palace he had built. The prince loved it, but though sunny it was in the middle of damp, windswept marsh, and conditions for the rank and file musicians, marooned away from their families, were not ideal.

This is the period of Haydn’s Farewell Symphony (no. 45) with its highly civilised yet pointed hint to the Prince about length of stay (and living conditions). By the end of the decade, the length of Summers in Eszterháza were reduced, and with a renegotiated contract meaning he could sell his music, Haydn discovered a whole musical world outside of the Prince’s domain, all eager for his music. This means that Haydn’s symphonies from this period, the late 1760s and early 1770s, have a particular feel to them. Effectively written for an audience of one, the conditions of Haydn’s employment meant that he was free to experiment. Interestingly, he rarely revisited this music in later life.

On this disc, Lars Ulrik Mortensen and Concerto Copenhagen give us three symphonies, all premiered during the period 1771 to 1772. All three have nicknames, but only one ‘Palindrome’ refers directly to the music itself, the other names were acquired later. Mortensen keeps his forces small, just nine strings, oboes, bassoon and horns, probably the sort of size Haydn expected after all even a small private orchestra was a lavish luxury in itself, but without the keyboard continuo that Haydn might have included.

We begin with Symphony No. 43 in E flat major ‘Mercury’, and an opening Allegro that mixes grace with crisp drama. There is an underlying energy here, too, and hints of sturm und drang under the surface. The slow movement has delicate, transparent textures with, I think, muted strings yet Mortensen and his players use detailed articulation to give it energy and an interesting darkness underneath. The robust yet graceful minuet and trio receives a compelling performance and the symphony ends with the light and fleet finale. Though there are moments of drama, it is the music’s inventiveness that comes over. In these symphonies, Haydn is experimenting and the devil is in the detail. With his compact forces, Mortensen really brings out that sense of detail.

Next is Symphony No. 44 in E minor, ‘Trauer’. Its nickname, ‘Mourning’ comes from the fact that Haydn wished its slow movement to be played at his memorial service! Things begin with an Allegro con brio that mixes striking unison gesture with minor-key responses. It approaches the sort of ‘listen to this’ gestures that Haydn would use in his public symphonies for London. There is an inventive irregularity to the music, and the players make the most of the contrasts. Once again they let us enjoy Haydn’s inventiveness whilst keeping the flow of the music going. The minuet and trio (the second movement here) features a canon. The music has a vigour to it, this minuet would have been quite a lively dance and whilst we detect the canon it is incorporated imaginatively into the music. There is an elegant grace to the Adagio that makes you wonder whether you are mistaken and that this is minuet, Haydn playing his games, but the music develops with varied countermelodies and attractively detailed textures. The finale’s drama is presented in a compelling yet intimate manner.

The final symphony on the disc is Symphony no. 47 in G major, ‘Palindrome’ whose name comes from the fact that its third movement minuet and trio are indeed palindromes. The lively first movement features perky rhythms including some lovely rhythmic horn writing that creates a nice juice texture at the begin. When things really kick off, however, we skitter away delightfully. This also, by far, the longest movement on the disc. It never palls but somehow does not feel mammoth, the players’ sheer delight really tells. The slow movement is austere in feel, yet intimate too, whilst the palindromic minuet is remarkably vigorous with plenty of accents. Oh, but how much fun must Haydn have had, writing music that not only worked forwards or backwards, but made musical sense. Then we finish with a finale that presents its material with a combination of delicacy and vivid energy.

The recording was made earlier this year in the Queen’s Hall in The Royal Library in Copenhagen. Whilst the name conjures up images of august 18th century interiors, The Royal Library is in fact a modern (1999) waterfront building in Copenhagen, nicknamed The Black Diamond; it does, indeed house a large extension to The Royal Library but also a handsome 600-seater concert hall whose event include regular appearances from Concerto Copenhagen [see events page]

There is something compelling about the detail and energy of these performances. Not the in your face, over the top energy, but an underlying sense that the music has an energy all of its own that comes from the detailed attention the players give it. The result is compelling in a way, in that this is playing that draws you in. Mortensen and players clearly love the music and that sense of love and joy comes over in these performances.

Joseph Haydn (1732-1801) – Symphony No. 43 in E flat major ‘Mercury’

Joseph Haydn – Symphony No. 44 in E minor, ‘Trauer’

Joseph Haydn – Symphony no. 47 in G major, ‘Palindrome’

Concerto Copenhagen

Lars Ulrik Mortensen (conductor)

Berlin Classics

Recorded 7-11 February 2024, Queen’s Hall, The Royal Library, , Copenhagen

BERLIN CLASSICS LCO6201 CD [71:08]

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Over-arching themes and influences: Andrew Ford’s The Shortest History of Music – book review

- Inventive and imaginative: Olivia Fuchs’ successfully reinvents Rimsky Korsakov’s The Snowmaiden for English Touring Opera – opera review

- Portraits of a troubled family: Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti & A Quiet Place at the Royal Opera House – opera review

- Leading with a love that inspires: Tafelmusik has a new collaboration with violinist Rachel Podger & a new disc of Haydn symphonies – interview

- A themed programme with an imaginative difference: Music from Pole to Pole with City of London Sinfonia and atmospheric physicist Dr Simon Clark – concert review

- Sound magic: En Couleur from the percussion group, Trio Colores – record review

- From expressionist nightmare to radiant energy: Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire & Schubert’s String Quintet at Hatfield – concert review

- Charpentier’s Actéon & Rameau’s Pygmalion: a perfect double-bill offering a delightful, entertaining evening – opera review

- Intimate & communicative: Solomon’s Knot brings its distinctive approach to Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 at Wigmore Hall – concert review

- Waiting till they feel they have something to say: I chat to Trio Bohémo about their debut disc – interview

- Home