|

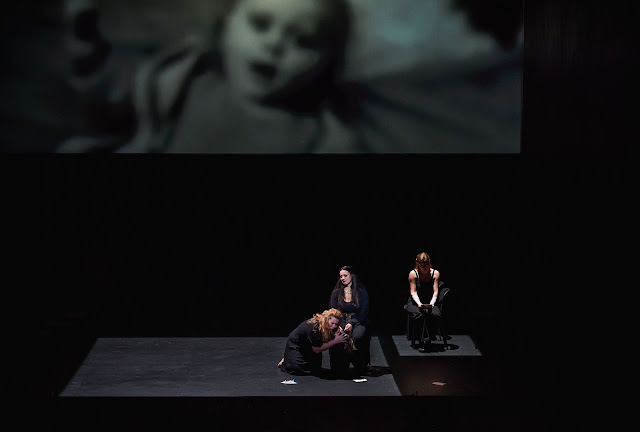

| Cherubini: Médée – Lila Dufy, Joyce El-Khoury in Act One – Opéra Comique (Photo: Stefan Brion) |

Cherubini: Médée; Joyce El-Khoury, Julien Behr, Edwin Crossley-Mercer, Lila Dufy, Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur, director: Marie-Ève Signeyrole, Insula Orchestra, conductor: Laurence Equilbey; Opéra Comique

Reviewed 8 February 2025

A powerful performance in the title role from Joyce El-Khoury in a production that adhered to Cherubini’s original vision, including sung French and spoken dialogue, yet gave a nuanced, modern take on the story.

Medea is the ultimate bad girl of opera, causing havoc, completely unrepentant and, in Lully, Handel and Mayr at least, escaping in a chariot drawn by dragons. The general view of Cherubini’s Médée is no different, she appears in Act One crying for vengeance and by Act Three, well, tragedy on a large scale.

Giving the original French version of the opera a rare outing, complete with spoken dialogue, at the Opéra Comique on Saturday 8 February 2025, conductor Laurence Equilbey and her ensembles Accentus and Insula Orchestra, and director Marie-Ève Signeyrole refocused the opera somewhat, giving Médée’s actions a more nuanced context. Médée was played by Joyce El-Khoury with Julien Behr as Jason, Edwin Crossley-Mercer as Créon, Lila Dufy as Dircé and Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur as Néris. Stage design was by Fabien Teigné with costumes by Yashi, lighting by Philippe Berthomé and video from Céline Baril and Artis Dzērve. The dramaturg was Louis Geisler.

Before we consider the production we should think about what we were hearing and why. Cherubini was long-lived, as the programme book pointed out, he was born four years after Mozart and died four years before Mendelssohn. His major operas were all relatively early works, Médée dates from 1797. It was was written as opera comique, though the combination of form and content was not uncontroversial at the time and the work was premiered not at the Opéra Comique but by another company at the Theatre Feydeau. Cherubini seems not to have been fond of the fully sung French opera, rarely writing them.

|

| Cherubini: Médée – Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur, Caroline Frossard, Joyce El-Khoury in Act Two – Opéra Comique (Photo: Stefan Brion) |

For him, Médée always had dialogue, even when performing it in Berlin and Vienna in German. In 1809 he produced a shortened version, in German, for Vienna (losing some 500 bars of music but keeping the spoken dialogue). Then in 1855, Franz Lachner produced this version in Frankfurt, replacing the spoken dialogue with his own recitatives. In 1909, this version was translated into Italian for the work’s Italian premiere at La Scala, Milan and it was this version that Callas sang.

We tend to favour this mongrel Italian version because, well, Callas. But consider that Médée was written just six years after Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte; would anyone nowadays consider performing Il flauto magico in Italian complete with sung recitatives?

Signeyrole’s production took place in a black box though lighting and video altered the atmosphere. Video sometimes was abstract, but more often depicted the characters, so we saw Médée’s entrance before the other characters, and sometimes the video was apparently live. From the outset, Signeyrole focused on the children, featuring them in the videos and giving them pre-recorded voice-over comments.

|

| Cherubini: Médée – Julien Behr, Joyce El-Khoury in Act Three – Opéra Comique (Photo: Stefan Brion) |

The production was apparently set in the modern day, but Yashi’s costumes were varied and distinctive in style with the female chorus in dresses that emulated earlier 20th century styles. Joyce El-Khoury’s Médée was definitely other, in Act One she was wearing what looked like traditional garb – Médée is from Colchis with is in modern Georgia. And in Act Two, she was living in a refugee settlement; she has been banished and the libretto states that she is living outside the city walls. The action in Act Three was vague, the temple represented by gauze curtain and there was no blood (instead a video of drowning).

During the overture the action moved between Jason, Médée and their children fleeing Colchis by boat, and Médée in prison reciting text inspired by Medea’s letter to Jason in Ovid. This latter was spoken by an actor, Caroline Frossard, who doubled Médée in much of the opera and, confusingly, in Act Three she mirrored Joyce El-Khoury’s actions as Médée made preparations to kill her children.

The intention was, I think, to link Médée’s actions to those of women everywhere suffering from domestic violence, but it made what was a powerful last act into something a bit too contrived. Jason, Créon and the men of Créon’s court were all depicted as violent and untrustworthy.

Edwin Crossley-Mercer’s Créon was a typical politician, suave and

poised with a lovely line in Cherubini’s music. Yet, happy to profit

from Médée’s action in Colchis (where she helped Jason steal the golden

fleece) whilst repudiating her for those very actions (killing her

father and brother). Also, in Act Two, Créon was happy to paw Médée and

consider her a sexual pawn. A terrific performance from Crossley-Mercer all round.

|

| Cherubini: Médée – Edwin Crossley-Mercer, Joyce El-Khoury in Act Two – Opéra Comique (Photo: Stefan Brion) |

His men were equally untrustworthy and the whole scene between Médée and Créon in Act Two was rendered more disturbing by the sheer violence that the men of Créon’s court treated the other women refugees, with Joyce El-Khoury’s Médée apparently powerless to act, trapped by her need to negotiate with Créon about her children.

Jason was just as bad and Julien Behr seemed to spend the entire opera with smoking or swigging alcohol. His Jason veered between extreme attraction for Médée and repulsion. Behr’s tone was heroic and rather intense, perhaps slightly too unvarying but overall a fine performance that managed to undercut the role’s heroic nature whilst never short-changing Cherubini’s music.

In this context, Médée’s dramatic journey became more understandable.

In Act One, El-Khoury was definitely not thundering vengeance, yet she

was a woman clearly on the edge. El-Khoury took Médée on a remarkable and comprehensible trajectory. There was a moment towards the end of her

Act Two scene with Edwin Crossley-Mercer’s Créon when we could see the

process slot into place. If she was to be deprived for her children then

so would Jason be as well.

|

| Cherubini: Médée – Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur, Joyce El-Khoury. Caroline Frossard in Act Three – Opéra Comique (Photo: Stefan Brion) |

By the end of the opera, this Médée was not triumphant but completely wrung out. There were moments when El-Khoury seemed slightly taxed in the upper register, but after all this woman was on the edge. El-Khoury brought the right combination of drama, vitality and weight to the music. If her performance did not have the dramatic heft of Callas, so what? In the present context that is as period as 1950s performances of Baroque music. What Joyce El-Khoury with Laurence Equilbey and Marie-Ève Signeyrole gave us was a Médée that was period appropriate in a style Cherubini’s might have recognised yet which resonated with the present day.

The other roles were well taken. Dircé, sung by Lila Dufy, is rather thankless. As Jason’s new wife she is the focus of Act One, yet is barely present in Act Two and dies off-stage. Lila Dufy was magnificent, managing to bring a sense of unease and nebulous doubt to the wedding celebrations. As Néris, Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur managed to suggest the warmly practical nanny/ nurse whose support for her charge/mistress led her on a terrible path, and Bouchard-Lesieur’s account of her Act Two aria was fine indeed.

In the pit, Laurence Equilbey and Insula Orchestra gave Cherubini’s music the drama it required whilst never pushing it into the late 19th century. I have heard performances where the blood and thunder of the drama pushed past Cherubini’s music into Verdian territory. Not here, thankfully. Equilbey and the orchestra found lots of drama on Cherubini’s own terms. And really, what a terrific score it is when you can hear all the detail of the orchestral writing. The chorus were part and parcel of this, providing fine support.

In one of the stage boxes there was also a bruiteur (what I have seen in the UK referred to as a foley artist), producing an array of noises and sound effects by remarkable means.

|

| Cherubini: Médée – Joyce El-Khoury in Act Three – Opéra Comique (Photo: Stefan Brion) |

This was a remarkable incarnation of a remarkable opera. Joyce El-Khoury’s Médée remained true to Cherubini’s conception yet gave a powerful modern twist to music and drama. There were times when I found the overall production rather too artful but the drama was always present and the result was powerful indeed.

Cherubini’s Médée – some performances

- 1797 – premiere at Theatre Feydeau in Paris with spoken dialogue

- 1800 – in German in Berlin with spoken dialogue

- 1802 – in German in Vienna with spoken dialogue

- 1809 – shortened version in German in Vienna with spoken dialogue

- 1855 – shortened version in German in Frankfurt, Franz Lachner’s recitatives

- 1909 – Italian translation of Lachner version with recitatives

- 1953 – Maria Callas’ debut in the role at La Scala in Lachner version

- 1959 – Maria Callas in Lachner version at Covent Garden

- 1984 – Rosalind Plowright at Buxton Festival in French with spoken dialogue

- 1989 – Valle d’Itria Festival in French with spoken dialogue

- 1989 – Rosalind Plowright at Covent Garden in French with spoken dialogue

- 1996 – Josephine Barstow at Opera North in English translation of the 1809 German version with spoken dialogue

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- To create modern culture through the thoughts of the past: George Petrou artistic director of the Göttingen International Handel Festival introduces this year’s festival – interview

- Another crazy day: Joe Hill-Gibbins’ production of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro returns to ENO reinvigorated – opera review

- My Heart’s in the Highlands: the debut recital from tenor Glen Cunningham mixes Stuart MacRae’s new songs with other composers with ‘Scotland in Mind’ – record review

- Unbearable intensity: musically strong revival of Janáček’s Jenůfa at the Royal Opera with incoming music director Jakub Hrůša on searing form in the pit – opera review

- Schubert’s Birthday at Wigmore Hall: Konstantin Krimmel in overwhelming form, with a welcome group of Carl Loewe too – concert review

- Bruckner’s obsession with death, Scottish Gaelic folk poetry & a grumpy gaboon: Scottish composer Jay Capperauld, Scottish Chamber Orchestra’s associate composer – interview

- Letter from Florida: a study in contrasts, Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette at Palm Beach Opera – opera review

- 1775 – A Retrospective: Ian Page & The Mozartists on terrific form in a deep dive into the sound-world of Mozart’s 1775 – concert review

- Canadian composer Jacques Hétu’s final symphony in a new recording with three of Canada’s major ensembles – record review

- Personal night time musings & reflections: Eight Nocturnes from violist & composer Katherine Potter commissioned by ABC Classic – cd review

- Home