|

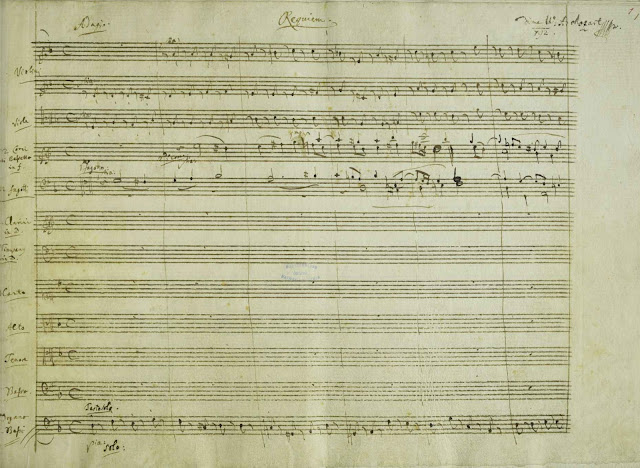

| The first page of Mozart’s autograph score of the Requiem |

Mozart: Symphony No. 35, Requiem, Bruckner, Rheinberger; Hannah Dienes-Williams, Bethany Horak-Hallett, Hugo Brady, Peter Edge, National Youth Choir (18-25 Years), Sinfonia Smith Square, Nicholas Chalmers; Smith Square Hall

Reviewed 17 April 2025

Vigour, flexibility and power with a lovely sense of impulse as the young singers of the National Youth Choir come together with the young emerging musicians of Sinfonia Smith Square in Mozart’s late masterpiece

As part of its Easter Festival at Smith Square Hall, Sinfonia Smith Square came together with the National Youth Choir (18-25 Years) under the choir’s principal conductor Nicholas Chalmers on Thursday 17 April 2025 for a programme centred on Mozart’s Requiem with soloists Hannah Dienes-Williams, Bethany Horak-Hallett, Hugo Brady and Peter Edge. The first half of the concert featured Mozart’s Symphony No. 35 ‘Haffner’ and motets by Mozart, Bruckner and Rheinberger, with the choral items intriguingly interleaved between the symphony’s movements.

This was a programme about youth, the choral singers were all in the 18 to 25 age bracket, the orchestral players are all emerging musicians hardly older than that whilst the four soloists are all rising stars. Sinfonia Smith Square brings together annually 34 young musicians in a programme aimed at bridging the gap between college and full time professional career. The programme aims to give the players real life problems, and the evening’s programme was not just a musical challenge, but had been put together in a remarkably short time (a skill that orchestral musicians must learn). Whilst Chalmers and the youth choir had, until a couple of days ago, been on tour in South Africa.

We began with Mozart’s Ave Verum, one of his last choral works (and probably written as a job application). Here it was performed by everyone, with the four soloists at the front of the stage and the 105 young choral singers, singing very quietly, surrounding the audience. An intriguing start to things.

Then whilst the choir members filed to their seats, Chalmers and the orchestra launched into the first movement of Mozart’s Haffner Symphony. Here, and in the Requiem, Chalmers pulled no punches with his speeds and the symphony began with vigour and excitement as he carried the young players with him. They gave a real sense of anticipation to the quieter moments and if these lacked an ideal sense of elegance, there was plenty of vim and vigour. We then moved straight into Bruckner’s unaccompanied motet Christus factus est, the choir combining youthful clarity of tone with firmness and flexibility. Whilst the climaxes were striking, there was real magic in the quieter moments.

The second movement of the symphony had a lovely sense of bounce in the rhythm, elegance, character and attention to detail being watchwords here, along with a nice delicacy. With any Mozart the devil is in the detail, and here the players got a lot right. Bruckner’s glorious motet Os Justi came next and again the choir impressed with its responsiveness. The climaxes, with their lavish tenor writing were given full force by the youthful tenors and basses, whilst the ending had a lovely hush to it.

The third movement of the symphony was a rather robust dance, but with graceful moments and this was followed by Josef Rheinberger’s youthful Abendlied, sung from memory to ravishing effect. The final movement of the symphony was full of crisp energy and perky bounce, though the speeds meant that some of the fast detail lacked ideal definition.

From the outset, the sound-world of the Requiem was very appealing. The choir’s sound was youthful yet strong, and there was a nice balance with the orchestra so that this was not one of those large-scale performances of Mozart’s Requiem that is choir dominated. And here, I was very (and delightfully) aware of the three trombones (guest musicians in the orchestra) who doubled the choral parts to striking effect. And if some of Nicholas Chalmers’ speeds were a challenge to the singers, they were even more so to the trombonists (a challenge they relished by the sound of it). The sound world of the Requiem is very linked to its use of trombones and basset horns in the orchestration, though here the basset horn parts were played on conventional clarinets which brightened the sonorities somewhat.

The Kyrie went at quite a lick yet never felt rushed and I rather enjoyed the vigour. This continued with the Dies Irae where Chalmers and his performers whipped up a great sense of excitement. After a fine trombone solo, the Tuba mirum continued with Peter Edge’s strong and well-focused bass, Hugo Brady’s ardent tenor with a very ingratiating top register, Bethany Horak-Hallett’s mellow mezzo-soprano contribution and Hannah Dienes-Williams’ warm soprano, already heard to striking effect in the first movement. After a strong yet brisk choral contribution in Rex Tremendae, the four soloists created a very concentrated expression in the Recordare. Again, Chalmers’ approach was quite speedy, but the soloists were all fluidly responsive, creating a sense of four individuals combining to one strong ensemble. The Confutatis was fast, headlong almost yet with light and transparent moments, whilst the Lacrimosa had a great swing to it.

The Offertorium began with a Domine Jesu that was alert with fine onward propulsion whilst the soloists provided four strongly contrasting voices in their contribution. In the Hostias there was a lovely contrast between the choral legato and the fine detail in the strings. Strength was to the fore in the Sanctus with fast yet robust Hosanna. Bethany Horak-Hallett’s rich mezzo-soprano led off the solo contributions in the Benedictus, followed by Peter Edge’s firm, vibrant bass and Hugo Brady’s almost Italianate tenor (he is certainly a singer I want to hear again in more solo repertoire), and finally Hannah Dienes-Williams’ warm soprano.

In the Agnus Dei, contrasts were to the fore, between strongly powerful and intense, and more gently intimate. With the Lux Aeterna we returned to Mozart’s opening, recycled by Sussmayr for the closing. Here Chalmers’ speeds did seem rather to provide a challenge for all, yet the overall result had an engagingly youthful sense of impulse.

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Looking at these modern classics anew: Britten’s Canticles at the Barbican with James Way, Natalie Burch & friends – concert review

- This production, will undoubtedly be remembered for years to come: Massenet’s Werther in Paris with Marina Viotti, Benjamin Bernheim & Marc Leroy-Calatayud conducting Les Siècles – opera review

- Compelling & magisterial: Sunwook Kim directs Chamber Orchestra of Europe from the piano in Beethoven’s 3rd & 4th piano concertos – review

- Letter from Florida: Mozart, Verdi, Rossini, Leoncavallo & Mascagni at Sarasota Opera’s Winter Festival – opera review

- An incredible feeling when you get it right; Martin Owen on performing Mozart’s complete horn concertos with Manchester Camerata – interview

- A somewhat eclectic yet satisfying journey: Swiss baritone Äneas Humm explores ideas of freedom in songs by Beethoven, Schubert, Amy Beach, and Joseph Marx – record review

- Remarkable intensity: powerful new 1980s-set Peter Grimes from Melly Still at Welsh National Opera with Nicky Spence – opera review

- Telling a musical story: violinist James Ehnes on the challenges of recording of Bach’s violin concertos with Canada’s NAC Orchestra – interview

- Powerful stuff: Ukrainian composer Boris Lyatoshynsky’s dramatic war-inspired symphony alongside Prokofiev’s Semyon Kotko – concert review

- Imagination & sense of drama: John Weldon’s 1701 prize-winning The Judgement of Paris in its first recording from Academy of Ancient Music & Cambridge Handel Opera Co – record review

- Home