|

| Peter Whelan conducting Mozart’s Symphony No.41 “Jupiter”, image taken from video filmed at the Whyte Recital Hall at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, 9/9/2023. Produced by November Seven Films. |

Conductor Peter Whelan is bringing the Irish Baroque Orchestra (IBO), of which he is artistic director, to the BBC Proms this Summer with a performance of Handel’s Alexander’s Feast. As with their performance of Handel’s Messiah at Wigmore Hall in 2023 [see my review], there is an Irish connection, and the ensemble will be exploring the version of Alexanders Feast that Handel produced for his visit to Dublin in 1742. As artistic partner of Irish National Opera, Peter has conducted the IBO in several productions, including two imaginative productions of Vivaldi operas, Bajazet in 2022 [see my review] and L’Olimpiade in 2024 [see my review]. It was recently announced that Peter will be the next artistic director of Philharmonia Baroque in San Francisco.

|

| Peter Whelan (Photo: Marco Borggreve) |

During an engaging couple of hours that I spent chatting with Peter, we covered a great deal of ground, but what struck me was not just his passion for the music but the way the story behind the music was important to him. He mentions as a child learning about Handel coming to Ireland and being taken with the story, this seems to have sparked an interest not only in music but in the stories behind it.

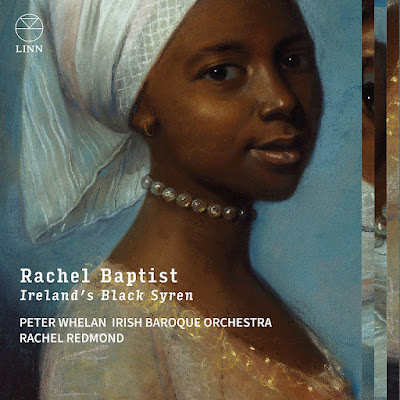

With IBO, he has produced a striking series of discs in Linn Records exploring Baroque music in Ireland by focusing on the stories of different characters from Irish musical history, illuminating the 18th-century musical life of the country. The most recent is Rachel Baptist: Ireland’s Black Syren, and others include Mr Charles the Hungarian: Handel’s rival in Dublin, The Trials of Tenducci: A Castrato in Ireland, and Welcome Home Mr Dubourg.

However, we began our chat with Handel’s Alexander’s Feast. During August, Peter and IBO will be performing this at Kilkenny Arts Festival, Dublin HandelFest, the BBC Proms at the Royal Albert Hall, and at Snape Maltings in Aldeburgh as part of Summer at Snape. To a certain extent, the choice of Alexander’s Feast for the BBC Proms was pragmatic; each year at the Proms, there is usually a big work by Handel and by Bach, and you need a grand work to fit the space. The performance would also be a chance to recreate the 1742 Dublin version of Alexander’s Feast, which has never been performed in modern times. And there is the additional benefit that the piece is about the healing power of music. Peter also proudly points out that the IBO will only be the second group from the Republic of Ireland to perform at the BBC Proms (the previous one was in the 1970s).

Handel wrote Alexander’s Feast originally in 1736, setting an adaptation of John Dryden’s Ode for St Cecilia’s Day (originally set in 1697 by Jeremiah Clarke), but Handel revised the work for subsequent performances and it was one of the scores he took with him to Ireland in 1742 when he was invited there. Peter has been working with the Handel scholar Donald Burrows on the 1742 version, which had very particular circumstances behind it. Handel intended to use the singing men from St Patrick’s Cathedral for his performance, but the Dean objected. The Dean at the time was Jonathan Swift, who was beginning to suffer his mental decline and had become somewhat cantankerous. The result was that Swift wrote what Peter calls an amazing letter to Handel announcing that none of the singing men could take part in the performance.

As a result, Handel lost his chorus and his male soloists. It is thought that he used theatre singers instead. The libretto and the conducting score for the Dublin performance both survive, the latter with the names of the soloists written in. The original Alexander’s Feast was in two parts, but this version was divided into three. Of the music, just one aria was missing. Donald Burrows found the bass part for the missing aria some decades ago, and along with the words (from the surviving libretto), he and Peter have been reconstructing the aria. Peter describes it as a fascinating process, reverse engineering the aria. When we spoke, he described them as nearly there, finding the process quite exciting.

He feels that there is great scope for engaging the culture of the past. There has been a big swell of interest in Irish classical music, with people thinking about who they are in a different way, in less colonial terms. In the USA, he has found that there is a big appetite from those of Irish descent for Irish culture that is not simply about getting drunk on St. Patrick’s Day.

|

| Peter Whelan & La Festa Musicale in Hannover (Photo: Nils Ole Peters) |

As we learn more about Handel’s stay in Dublin, it becomes apparent that the musical standards were somewhat higher than commentators originally believed. Many of his musicians were taken from the Irish State Music at Dublin Castle (home of the Viceroy). Many of these were outsiders, including a lot of Hungarians. One such was the violinist Matthew Dubourg, who was illegitimate, and it is worth remembering that when he took a job in Dublin, it was the second largest city in the Empire. The violinist Francesco Geminiani (who was Matthew Dubourg’s teacher) lived in Dublin for a time, but though he taught there, he could not have an official post as he was a Roman Catholic.

There was also a lot of crossover with traditional Irish culture. Peter tells a story about Matthew Dubourg going to a country fair dressed up as a fiddler in order to get Irish tunes, and being mobbed when the local musicians realised the quality of the violin Dubourg was playing. There is a manuscript by Dubourg of Irish tunes with the Gaelic words written phonetically, and one sketch has an Irish tune on one side and ‘He was despised’ from Messiah on the other.

Peter has been on a journey to show that classical music belongs in Ireland. He points out that pianist and composer John Field’s father worked at Dublin Castle, whilst the tenor Michael Kelly’s father was a wine merchant, and all the musicians went to his place for a drink. Kelly would go on to create the roles of Don Curzio and Don Basilio for Mozart in Le nozze di Figaro, but as a young man, he had met all the Italian singers visiting Dublin at his father’s bar.

Whilst the world of recording is fading, recordings are still a calling card, and Peter feels you can pull people in through a story or narrative. He finds that there is no end to stories for inspiration; you come across another little character from history that you cannot quite let go of. He is spurred on by the story-telling; for a lay person, classical music can be intimidating, and stories attached to a place, or a narrative about a character from history, can draw the audience into the tale.

Peter mentions the porter who carried people’s instruments, but who was accused of body-snatching and deported, or the Italian violinist Pietro Castrucci, who moved to Dublin when he got older and died there, destitute. Then there was the castrato Tenducci (subject of IBO’s disc The Trials of Tenducci: A Castrato in Ireland), who lived in Ireland and seduced an Irish lady, Dorothea Maunsell. At one point, he was in Cork jail. The pair were chased out of Ireland and reportedly seen by Casanova, living in London as a couple with children! IBO’s most recent disc shines a spotlight on the career of Rachel Baptist, who was a Black soprano, big in the 1750s. Little is known about her beyond what she sang and the fact that she wore a yellow dress, but it is likely that 18th-century Dublin was somewhat more accepting than London.

Sometimes, Peter admits, sometimes the character might be interesting, but the music associated with the person is not as great. However, he feels that there is always space for this repertoire as it puts the better-known works in context. He read music at Trinity College, Dublin, and music books were dismissive of the music in Ireland. At a certain point in his career, he decided to explore this music himself, founding Ensemble Marsyas for the purpose, directing from the keyboard. This enabled him to explore music such as the Royal Birthday Odes written for performance at Dublin Castle.

He was curious about why Handel came to Ireland in 1742. There was a small but active concert scene in Dublin at that period, and there is a letter written by Handel where he says that the Dublin musicians were excellent. Handel was close to Matthew Dubourg, who was concert master at Dublin Castle from 1728 to 1764, and in fact, Dubourg was the only musician to whom Handel left money in his will. And Dubourg’s son-in-law wrote that Handel had a stroke whilst he was in Dublin, but he was staying in the Surgeon General’s House and was nursed back to health.

There are so many interesting tales to tell, particularly in the way communities travel, that Peter feels his story-based approach will continue. The stories behind the individual solos can be incredible. He mentions the Dutch oboist, Jean Christian Kytch, who was known as ‘Handel’s oboist’. When he could no longer play, he became destitute, and the plight of his children after his death reputedly prompted the establishment of the Fund for the Support of Decayed Musicians and their Families (now the Royal Society of Musicians). Handel contributed generously to the fund.

|

| Irish Baroque Orchestra & Peter Whelan (Photo: Pawel Bebenca) |

There there is only so close that you can get to the past, some things will be unknowable. However, there is now a community of people who love the music and how it sounds, and are researching further. Society is so fragmented that musicians are never going to compete with Netflix, but for Peter, classical music is a place where you can bring people together at the same time. And after all, music only really comes to life when there is a live audience. This forces people out of their individual bubbles; you have to engage with the communal reaction to the performance.

Besides period instrument ensemble, Peter also works with modern orchestras, and he is conducting the Scottish Chamber Orchestra in Mozart in December 2025. Whatever the style of instruments, Peter feels that the audience needs to feel the rhetorical aspect of the music. Working with modern instruments, he has to use a different language to bring the music alive to the musicians. It is a case of wearing your knowledge lightly and finding the right simile, the right image and one example he uses refers to 1980s cartoons.

Peter made his debut with Philharmonia Baroque in San Francisco in March 2025 when he conducted them in Handel’s Alceste. The orchestra was founded over 40 years ago, and he finds it interesting to go so far away from home, and then meet people who studied in the same places. The orchestra’s founders all studied in The Hague; they are at home both in Handel and in French Baroque, and Peter will be running with that in his programmes with them, but taking things to the next level. The musicians are a mix of founders and younger players, a mix of experience and mentoring young musicians. He comments that there is something about the air and the light there, with people hungry for Baroque music yet in a place so modern.

For much of his early career, Peter was known mainly as a bassoonist. He still holds onto the instrument a tiny bit. He teaches at the Royal Academy of Music and has nine dedicated students. He loves teaching and finds that it helps to sharpen your tools as you have to explain things.

Peter harks back to the 1960s, when in both the Early Music movement and in contemporary music, musicians were prepared to do things and not be liked. He feels that there is still scope to shake things up in a similar way in historical performance practice today, to do funky experimental things, but funding is difficult.

At the end of our two hours, our talk moved on to the 19th century. Peter does some work with the modern-day successor to the Meinigen Hofkapelle with whom Brahms worked a lot (and where Mühlfeld, the clarinettist who inspired Brahms, worked). Peter produced an intriguing quotation from Brahms, who said that vibrato was for wind players but not strings!

Handel: Rodelinda – Garsington Opera, The English Concert, Peter Whelan

- 19 July

Handel: Alexander’s Feast – Irish Baroque Ensemble, Peter Whelan

- 14 August – Kilkenny Arts Festival

- 15 August – Dublin HandelFest

- 30 August – BBC Proms

- 31 August – Snape Maltings

Grieg, Handel, Telemann – Det Norske Blåseensemble, Peter Whelan

- 18 September – Fredrikshald Theater, Norway

- 19 September – Universitets Aula, Oslo, Norway

Bach: Mass in B Minor – Irish Baroque Ensemble, Peter Whelan

- 1 November – Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin

Mozart Matinee: Serenade KV 320 ‘Posthorn’, interspersed with arias from Mitridate, La clemenza di Tito, Così fan tutte and The Marriage of Figaro.

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Peter Whelan, Tara Erraught

- 17 December – St Andrews

- 18 December – Edinburgh

- 19 December – Glasgow

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- A moving immediacy and directness: British Youth Opera in Britten’s Peter Grimes with Mark Le Brocq in the title role – opera review

- We were transported: local history and engaging performances in Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore at St Paul’s Opera – opera review

- A game changer: as RPS Conductors programme enters a new phase, I chat to founder Alice Farnham & an early participant, Charlotte Corderoy – interview

- A quartet of concerts ended a marvellous, fulfilling and enjoyable Aldeburgh Festival – concert review

- A vivid theatricality that a more conventional treatment might have missed: Bintou Dembélé & Leonardo García-Alarcón collaborate on a remarkable reinvention of Rameau’s Les Indes Galantes – opera review

- Robert & Clara: Stephan Loges & Jocelyn Freeman at SongEasel – concert review

- A vivid sense of style & stagecraft with some of the best Handel singers around: Rodelinda at Garsington – opera review

- A different focus: Timothy Ridout in Mozart & Hummel with Academy of St Martin in the Fields plus Rossini & a Weber symphony – concert review

- From Handel to Verdi & beyond: Soraya Mafi on singing in Handel’s Saul at Glyndebourne, expanding into bel canto & Bernstein – interview

- An alternative way people can encounter classical music: Baldur Brönnimann & Felix Heri introduce Between Mountains Festival – feature

- Home