|

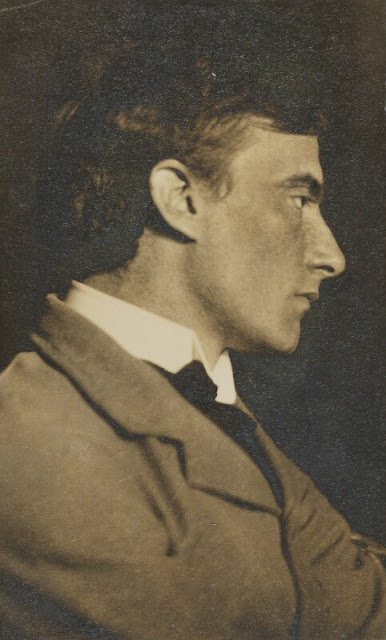

| Edward Thomas by Frederick Henry Evans bromide print, circa 1904 NPG P476 © National Portrait Gallery, London |

On 17 September 2024, St Martin-in-the-Fields opens its 2024/25 season with the London premiere of Alec Roth’s song cycle A Road Less Travelled, performed by tenor Mark Padmore and Morgan Szymanski on guitar. Roth composed his song cycle for Mark Padmore to commemorate the centenary of Thomas’s death at the Battle of Arras in 1917; it was commissioned by the Autumn in Malvern Festival for its premiere in September 2017.

In advance of the London performance, I was able to have an email conversation with Alec Roth (who is based in Germany) about the cycle.

RH: Can you introduce A Road Less Travelled?

AR: A Road Less Travelled is a work for tenor and guitar and/or string quartet, with words by Edward Thomas (1878- 1917), lasting about 35 minutes. It was commissioned by the Autumn in Malvern Festival and first performed by Mark Padmore, Morgan Szymanski and the Sacconi Quartet in Great Malvern Priory in 2017.

The title A Road Less Travelled is a reference to the well-known poem by Robert Frost, The Road Not Taken. Less well known is that the poem is about Edward Thomas. As Frost explained, Thomas was “a person who, whichever road he went, would be sorry he didn’t go the other”. This gentle mocking of indecision has been misunderstood and taken for something more serious, not least by Thomas himself (it has been suggested that Frost’s poem was influential in Thomas’s decision to enlist in the army).

When the two first met in 1913, Thomas was known as a nature writer and book reviewer. Frost heard something distinctive in Thomas’s style, and during their walks together through the countryside around Dymock and the Malvern Hills in the summer of 1914, he encouraged his friend to turn to poetry.

Thomas produced some 140 poems in little more than two years before his death at the battle of Arras in 1917. He mentions the war, but it is never centre-stage in his verse, which is focussed on the natural world and our existential relationship to it. In Andrew Motion’s words, Thomas’s poems “brilliantly prove that you can speak softly and yet let your voice carry a long way”.

RH: The work was written for the centenary of Edward Thomas’ death, what is it about his poetry that drew you to set it?

AR: Mark Padmore’s second CD of my music Sometime I Sing (2011) featured works composed for him and the guitarist Morgan Szymanski. We were short of a filler item to make up the disc, so I quickly prepared a setting of Edward Thomas’s poem Lights Out, which had been haunting me ever since I came across it in an anthology. The song seemed to write itself, and I made further use of it in a choral version for my cantata A Time To Dance (recorded by Ex Cathedra in 2016). I was prompted to investigate Thomas’s other poems by the realisation that 2017 would mark the centenary of his death. His poetry has a simplicity and directness of utterance which invites musical setting, but also a richness of imagery and metaphor which stimulates the imagination.

RH: In a work like A Road Less Travelled, focusing on a single poet, how do you plan the structure of the song cycle?

AR: It was clear to me that the piece had to end with Lights Out – I couldn’t conceive of anything (words or music) which could follow it. So I set to work reading through all of Thomas’s poems. Roads was clearly a favourite theme, so the idea of a journey soon emerged (perhaps influenced by my love of Schubert’s Winterreise). By this time I had discovered that Robert Frost’s poem mentioned above was actually about Edward Thomas, so a journey through the beauty of the English countryside, but also an interior journey through doubt and indecision.

He writes about the natural world with an immediacy which can be startling and moving. As I got to know the poems, I became aware of certain recurring thoughts and images: an old man; a child; bird song; the dead oak tree; rain; snow; night; silence; and the inevitable forest of Lights out – the forest a metaphor for sleep; sleep a metaphor for death.

There was no shortage of material; I simply had to spend a lot of time searching and sifting. But the key question for any text is will it set well to music? My way of discovering this is to take the words for a walk, speaking them out loud, internalising their inherent musical qualities and discovering whether they move me, and how they make me move. For a large work of this kind, there is the added complexity of finding how the texts speak to each other in different proximities and relationships. To some extent I had to work backwards to ensure that the journey through words and music progressed with a feeling of inevitability, culminating in Lights Out.

Assembling the text was a time-consuming process, but one in which much compositional activity must have been going on subconsciously, because when I had the words finalised, the musical setting progressed relatively quickly. But even now, I’m discovering interesting cross-currents in the words which have clearly influenced the music, but which I was not aware of at the time.

RH: A Road Less Travelled is one of a number of works you have written for Mark Padmore, what is it about his voice and his performances that appeals to you?

AR: My setting of words requires that they be clearly heard and understood by the audience; Mark is brilliant at delivering text and music as a natural-sounding and seamless whole, and his mastery of the Evangelist roles in the Bach Passions makes him a wonderful story-teller.

RH: Many of your songs avoid the classic combination of voice and piano, using guitar, oboe, harp etc as accompanying instrument. Is this deliberate, or happenstance?

AR: As you say, voice and piano is the “classic” combination, but I have only composed for that line-up when a commission has insisted on it, and not by choice. My reasons are too many and various to go into here, but although some pieces can be (and are) performed with keyboard, to me, my music never feels really at home on the piano. Perhaps it is the essentially modal nature of my music which doesn’t sit well with equal temperament. But I haven’t bothered trying to analyse; it just doesn’t taste quite right. So I don’t think of myself in the classical tradition of Lieder (although, like most song composers, I adore Schubert), but rather in the much earlier English tradition of John Dowland and his contemporaries, with their flexible alternation between lute and viol consort (in my case, guitar and string quartet).

I love the guitar as a solo instrument and as a true and equal partner for the voice. It makes the experience of a song recital wonderfully intimate, drawing the listener into its subtle sound-world of colours and textures; and (especially in Morgan’s hands) the guitar can really sing.

I met Morgan when he was still a student at the Royal College. I used to lead training workshops for Live Music Now, preparing young professionals to go out into the community and make music for any kind of audience in any setting. As soon as I heard him play, I was entranced by the way his performance captivated everyone in the room. So began a very fruitful relationship, starting with The Unicorn in the Garden, which I composed for his Wigmore Hall debut recital in 2003.

One of the few things of which I admit being proud, is bringing Mark and Morgan together. The many songs and song-cycles I have composed for them have been a joy, but also a great learning process for me, not just in the technical intricacies of writing for voice and guitar, but also in the inspiration provided by working with artists of such insight and creativity.

RH: When writing songs and song cycles, who would you say your biggest influences were?

AR: For songs and song-cycles, the biggest influences on my music are the text, and the musicians I am composing for. But the “who” in your question suggests that you mean other composers. This is not something I give much thought to. It’s like asking why do you walk the way you do, or speak the way you do? I’m just intent on where I’m going, or what I want to say. We are what we eat; and since it’s a question of taste, that applies in music too. Someone whose musical memory-banks are nourished by copious helpings of say Rameau; Eisler; Dangdut; Haydn; Elgar; Ravel; Reggae; Isaac; Nono or Gagaku, might initially hear their echoes in a piece of music new to them (whether they are actually there or not), because listening is a creative process of making musical sense of what we hear. The process will vary from listener to listener according to their accumulated experience and tastes. And nowadays when every conceivable kind of music is instantly accessible at the click of a mouse, the possibilities are legion.

But I digress. My influences? Well, the years I spent in the study and practice of Javanese music have been a huge influence. What interests me is adapting the deeper structures and compositional principles of gamelan music to Western resources. Steve Reich put it quite neatly: “one can study the rhythmic structure of non-Western music and let that study lead where it will, while continuing to use the instruments, scales and any other sounds one has grown up with”. One of the most formative things I grew up with was singing, so I feel very much at home composing vocal music.

But one must always remain open to new ideas and experiences. As a freelancer I’ve mostly had to work to commission, envying university composers for their sabbaticals. So it was a wonderful gift in 2015 when I was awarded a Finzi Scholarship, enabling me to spend a few months in Leipzig studying the cantatas of J S Bach – not an academic study, but as an inspiration for my own music. This turned out to be an unexpected influence on my Edward Thomas settings, which were slow-cooking at the back of my mind at the time. Of course, my music doesn’t sound anything like Bach, but I was fascinated by his manipulation of his texts, and the variety of musical treatments he subjected them to. So rather than “song cycle”, I have called this work a “solo cantata”, since, in addition to song, it adopts and adapts other musical forms associated with the cantata – recitative, aria, arioso, a purely instrumental movement, etc. – in varying combinations and permutations, sometimes with the words in the driving seat; sometimes the music; always (I hope) in a creative balance.

RH: When it comes to choosing words to set, what do you look for in a text?

AR: As with musicians, I’ve learned much from working with living writers, and in particular Vikram Seth, with whom I have collaborated on many projects. This has gradually given me the confidence to assemble my own selection of texts from other authors – whether a composite from different poets on a particular theme, or, as in this case from a single author.

It might sound fanciful, but sometimes I feel that it is actually the texts which find me – a chance glance at a newspaper article, a random turning-on of the radio. One just needs to keep one’s ears, eyes, and mind open. Of course, putting myself in a situation where words might easily find me helps, so I spend quite a lot of time in libraries. I’ve often been blessed by serendipity – a moment of recognition when we read or hear something which arouses thoughts and feelings that move us and resonate deeply, but which we would struggle to express in words ourselves. And sometimes I hear such a text saying to me: “OK, I’ve got your attention; now set me to music”. Bingo!

RH: Are you working on anything at the moment?

AR: Nothing completely new just now, but revising a number of old works for publication.

|

| Alec Roth |

RH: Are there any other major performances coming up?

AR: The thing I’m most looking forward to in 2025 is the release on the Signum Classics label of a new CD of some of my chamber music with voice. In addition to A Road Less Travelled, performed by Mark Padmore and Morgan Szymanski, it will include two song cycles: The Garden Path, settings of poems by Amy Lowell, sung by the mezzo Martha McLorinan with the Sacconi String Quartet; and Other Earths and Skies, for tenor and oboe, with words by the Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai in Vikram Seth’s English translation, performed by Hugo Hymas and Nicholas Daniel.

Since December 2020 I’ve been based in Germany, so most of my focus has been on performances there, including a major commission as Composer-in-Residence to the RIAS Chamber Choir Berlin for its 2023-24 Jubilee season celebrating its 75th anniversary. Later this year my cantata A Time To Dance will have its German premiere in Ludwigsburg, and next year I have a premiere in Leipzig – a motet to a very moving text by Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

I’m planning to move back to the UK in 2025, and look forward to re-establishing musical connections there – and seeing where my own ‘road less travelled’ might lead me next.

Crypt Close-Ups: Mark Padmore & Morgan Szymanski

17 September 2024, St Martin-in-the-Fields

Songs by John Dowland and Schubert, folksong arrangements by Britten, Alec Roth’s A Road Less Travelled – further details