The Ravel is just fine – swift, efficient and pleasant, with some excellent woodwind playing. However, I was shocked at how extremely recessed the orchestra sounds on this recording, revealing the enormity of the vast, empty church in which it was recorded. In addition, the acoustic is more reverberant than usual with this orchestra – and curiously more so in this Ravel than in the remainder of this very same program. I’m glad Mr. Couzens fixed it before they got any farther along in the recording session.

The Prelude is lush and shimmering in a way a piano could never be, and it’s played up to the speed most pianists do. (It’s actually more difficult in the orchestral version, with some very challenging oboe and clarinet writing.) Unfortunately, some of the delicate detail is rather glossed over at this tempo and lost in the reverb. Similarly, Forlane is much faster than usual (either by pianist or orchestra) but the results are positively delightful. I’ve rarely heard such charm from John Wilson before, aided by wonderful playing from his orchestra.

The final two movements are more traditionally paced, with some very expressive oboe playing in the Menuet. Unfortunately, Rigaudon loses some impact with the trumpet placed so far away – way, way back in the hall – minimizing its arpeggiated mini-fanfares. The strings are nicely articulate, but the reverberation is at its most obvious here and rather detracts from the otherwise lovely music-making.

Instantly with the Berkeley, the orchestra is less recessed and has gained presence. It’s not more forward (thankfully), it’s just better focused and more immediate. And the brass have rejoined the rest of the orchestra and the trumpets now command a more impactful contribution. All of which is good.

But we’ve got to address the serious – and recurring – issue with John Wilson and his string section. What is it with his penchant for insisting his violins play with this bizarre, frenzied, hyper-fast vibrato? It is extremely annoying – not to mention inappropriate – in Classical music, especially here in Berkeley’s charming Divertimento. I think Wilson thinks it adds intensity, but it goes way beyond that. It becomes downright frenetic by the time the central section of the Nocturne arrives, spoiling the emotional melodic line. And it’s so frantic in the Scherzo, it adds angst where none should be. The more I hear it, the more irritating it is.

The finale comes off best. After a brief introduction, the Allegro generates plenty of gusto and keeps the strings busy enough they can’t be bothered with that vibrato nonsense. The propulsive energy here is arresting, though perhaps misses some of the inherent charm in this music. But Wilson relaxes beautifully in the central meno vivo section and the piece ends enchantingly.

Amazingly, there is only one other recording I can find of this marvelous Divertimento – conducted by the composer himself in the 1970s with the LPO (available on a Lyrita CD). While I haven’t heard that for comparison, I can’t help but think Wilson is perhaps trying to make more out of this little piece than there is to it. The booklet quotes how other musicians and composers of the time described it back when it was first composed in 1943 – including descriptors such as “light”, “pretty”, and “balletic”. But Wilson minimizes all that, instead making it rather melodramatic and overladen with anxiety, exacerbated by his anxious violins. However, in the end, there is no denying the vigor and enthusiasm he brings to it, in the typical John Wilson way of whipping up excitement.

At last we come to the highlight of the program – the 3rd Symphony by Adam Pounds, written during the Covid-19 pandemic and dedicated to John Wilson and the Sinfonia of London. And everything about it on this recording is an improvement over the previous two selections – from the playing, to the leadership from the podium, to the recorded sound. And I’m so pleased producer Brain Pidgeon saw fit to place it last on the program.

The opening Largo instantly sets a tone of passion and anticipation, with some gorgeous solos among the woodwinds (notably the flute). It is soon followed by a very energetic and propulsive Allegro, which barely takes flight before relaxing back into emotionally charged melodic passages. Wilson is superb at characterizing the variety of moods here – from dramatic to beautifully expressive – and the playing and recorded sound are very impressive.

A rollicking but somewhat cumbersome Waltz in a minor key takes the place of a traditional scherzo. The booklet describes it as a danse macabre, while the composer associates it with Shostakovich. I hear all of those elements, but heavier than typical of a waltz, and Wilson wisely propels it forward with infectious momentum, preventing it from weighing itself down.

The slow movement Elegy is an homage to Anton Bruckner. And if you’re a fan of Bruckner (which I am not), you won’t mind its 8 minutes length. Fortunately for me, I don’t hear actual Bruckner in it. It’s simply gorgeous music, with passion and real angst. It’s very moving and inspiring, and Wilson brings the most out of it (and his strings are well-behaved). I do wish it had ended with the interesting, introspective pizzicato section in the middle, before recapitulating the main theme, which I felt allowed it to go on just a bit too long.

The final Allegro moderato takes off with propulsion and vigorous articulation, with hints of Vaughan Williams in a robust mood. Even with all its energy, it’s filled with emotion and anguish, still in a minor key. A very moving Largo appears with deep reflection, which is more suggestive of Shostakovich than anything else in the entire piece. The zest of the opening returns, leading to a rather wistful conclusion, with no superficial attempt to dazzle just for show. And it’s all the better for it. It is a fitting and appropriate ending for the mood and scope of the piece – especially given the subject matter which inspired it.

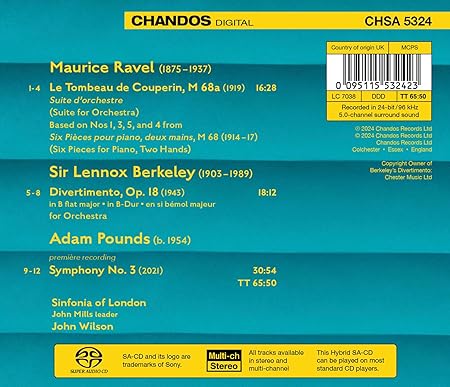

This is a notable and important new British symphony, given the best possible advocacy by John Wilson and company. The Chandos recording is excellent and the playing is sensational. But it occupies just 30 minutes of this disc.

As to the rest, the Ravel is a pleasant bonus (despite minor reservations with the recording), but it’s a real pity the Berkeley is marred by this weird vibrato Wilson elicits from his violins. It was one thing hearing it on his album of classic Hollywood film scores, but it’s entirely out of place in serious orchestral music. It’s an annoying gimmick which is cropping up too often and becoming more pronounced in some of his newer recordings. For god’s sake, will someone please tell him to stop it? It’s absolutely ridiculous.

%20Craig%20Fuller.jpg?w=160&resize=160,160&ssl=1)