|

| Stéphane Fuguet & Les Épopées (Photo: Pascal Le Mée) |

In June 2024, harpsichordist, conductor and director, Stéphane Fuguet and his ensemble, Les Épopées are releasing their recording of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo on the Château de Versailles Spectacles label with tenor Julian Prégardien in the title role. This is the second of the ensemble’s survey of Monteverdi’s operas on disc, they released Il ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria in June 2022, and L’Incoronazione di Poppea will follow in April 2025. In March 2024 the ensemble released, also on the Château de Versailles Spectacles label, the final volume of their survey of the complete Grands Motets by Jean-Baptiste Lully.

Stéphane comments that every conductor has their own ideas for L’Orfeo. He is intensely interested in the approach to declamation in this period of opera, the particular combination of melody and text in Monteverdi’s recitar cantando (speaking through singing). He has heard this music done almost as if the singer were speaking, and this willingness to explore is something that characterised their recording of Il ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria and continues in the new release. But there are other areas too, where the surviving printed materials do not give us the whole picture, performers need to make decisions and choose their approach.

Stéphane points out that whilst the score indicates what instruments are to be used, the musical material is not fully written out; at the beginning of the score there is a list of instruments which does not tally with those present in the score. For example, at the beginning of the score, three violas da gamba are mentioned, but there is never any music for the three. What to do with them? It is this gap which gives performers the space to be creative. Stéphane adds that as the instrumental writing is usually in five parts so one could use a type of broken consort, having different line-ups.

The realisation of the continuo part also gives scope and Les Épopées realise it in different ways, making use of the structure of the piece, bringing out different textures according to context, so that there are moments when Monteverdi seems to have textures that get bigger, suddenly different to a simple realisation for lirone. Additionally, everything is improvised, Stéphane never writes the music down, keeping it moving and always changing.

|

| Stéphane Fuguet (Photo: Ludek Brany) |

Part of the attraction of the opera is the way that the character of Orfeo is touchingly human, he doubts himself and at the end turns back toward Euridice, showing a real human fragility. For the title role, Stéphane was looking for a singer who could do something fragile, at different moments murmuring and screaming. Stéphane has known Julian Prégardien for around a dozen years and admires him because whilst his voice can be very sunny, round and emotional, he is also willing to try things out, there are no limits.

I was interested to know what a French ensemble that performs a lot of 17th French music made of Italian declamation in operas like L’Orfeo, but Stéphane turns the issue around, pointing out that French declamation comes from the Italian, with the young Lully listening to Italian opera in Paris and trying to notate it. For Stéphane, Italian opera is the beginning. He has taught at the Paris Conservatoire for the last 12 or 13 years and performs two or three operas per year with the students (some staged, some in concert) and they have done a lot of Italian 17th-century operas by Cavalli, Rossi, Peri and Monteverdi. This has involved working on the recitatives, which he feels are very close to talking. And he points out that there are more ornaments in French declamation as the tension can come from these.

In March this year, their fourth and final disc in their survey of Lully’s complete Grands Motets was released. These were works written for special occasions in the Royal Chapel at Versailles, and Stéphane finds something rather theatrical in them. For Stéphane, Lully approaches the music from a position of theatrical oratory, the priest talking to the people. Stéphane explains that a lot of the declamation treatises of the period were for opera, theatre and church, so a priest’s sermon could use the same musical/theatrical qualities as singers or actors. What is strong in Lully’s Grands Motets is the largeness of the structure for choir and orchestra, sometimes setting the text homophonically but also in a theatrical way. Lully’s approach is very different to the other composers of chapel music at Versailles, and Stéphane sees Lully’s theatricality as being connected directly to his tragédies lyriques, and he brings in the analogy of Verdi writing his highly theatrical Requiem.

|

| Stéphane Fuguet & Les Épopées (Photo: Pascal Le Mée) |

Since July 2020, Les Épopées has been in residence at the Château de Versailles, and the recordings of Lully’s Grands Motets and Monteverdi’s operas are made there, but Stéphane is at pains to point out that the Versailles of Lully’s time was rather different to the Versailles of today. The present chapel was not completed until 1710 (it is the fifth royal chapel to be built at the palace). But for Stéphane, the building has a very special acoustic with a long reverberation, yet the sound is clear and crystalline. It is not only absolutely beautiful to the eye and the ear but also a very suitable acoustic for recording Lully’s Grands Motets.

For the regular music in the Royal Chapel, relatively few performers would be used, but for the grander occasions, when the Grands Motets would be performed, a larger group was brought together, an extraordinary union of musical forces, strings (who normally accompanied church music), wind (who normally played outside), choir and soloists. For these extraordinary occasions, Lully puts them all together and they used almost 100 performers for the recording of Lully’s Te Deum, whilst in the 18th century there may well have been up to 150 performers.

Stéphane had an ensemble that included some seven trumpets. But also children aged 11 to 14, as a result of their collaboration with the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles which specialises in music of the 17th and 18th centuries. The remainder of the choir were adults, but Stéphane tried to have the children’s voices at the centre of the sound, creating what he feels was a touching atmosphere. When working on the French repertoire, Stéphane considers that ornaments were added to the score by the original performers, but in a way that does not interrupt the line.

|

| Lully’s Alceste performed in the Cour de Marbre at Versailles in 1674 |

The Royal Opera at Versailles was not inaugurated until 1770 and prior to then opera was performed in a variety of places. When Stéphane and Les Épopées performed Lully’s Alceste, they gave it in the Royal Opera, but for the recording, they used the Salles des Croisades, where they have been recording Monteverdi’s operas and their Charpentier disc. During King Louis XIV’s time, opera performances could take place in different locations including the stables and Lully’s Alceste was performed outside in the Cour de Marbre, but it was also performed in the Palace of Fontainebleau and at the Paris Opera, where Alceste was the first production after the company moved into the Théâtre du Palais-Royal. So there is no definitive way to perform the opera because there is no definitive location from the period.

Also, Stéphane points out that there is no definitive version of Alceste, the work was far more malleable than it appears. We have the original libretto, which means we know the names of the performers, but no complete information about the forces used. For the Fontainebleau performances, the names of the instrumentalists are all wind players, but for the performances at the Paris Opera, Lully seems to have created a new version where the oboes often double the strings. This is a new idea, before this, scoring tended to be structured, separating strings and wind into blocks. This is what happened at Versailles and Fontainebleau, but for the Paris Opera performances the sound is not structured, Lully mixes things up. So the performers have choices, and in his version Stéphane is selective sometimes using only strings, sometimes only wind and sometimes together.

Stéphane finds opera in the first part of the 17th century, from Monteverdi to Rossi, rather fascinating as the idea of bel canto seems to be developing, recitative tends towards talking with a greater emphasis on arias so that the later 18th-century style of recitative and aria is coming about. The company will be releasing their recording of Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea in 2025, and will then continue their exploration of 17th-century Italian opera with Stefano Landi’s La Morte d’Orfeo which was first performed in Rome in 1619 and deals with the Orfeo story after the end of Monteverdi’s opera, where Orfeo returns to earth and has to deal with the Furies. Also in their sights is Luigi Rossi’s Orfeo, which tells yet another version of the Orfeo story. The work is an Italian opera written for France, premiered at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal in Paris in 1647, and is one of the earliest operas to be staged in France. Stéphane sees the music as being somewhat between Italian and French.

|

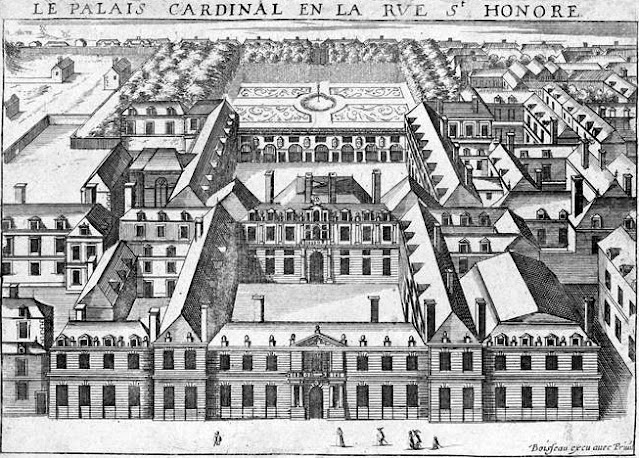

| The Palais Cardinal (future Palais Royal, Paris) in 1641 The theatre is to the right of the image |

Rossi’s Orfeo was staged under the patronage of Cardinal Mazarin, the expense of the performance was just one of many reasons stoking popular discontent against Cardinal Mazarin which soon broke out into full-scale rebellion (the Fronde). When Rossi returned to Paris in December 1647, he found the court had fled Paris and his services were no longer required. Cavalli would also come to Paris in the 1660s, but then taste turned away from Italian opera towards creating a specifically French opera and the Paris Opera (Académie Royale de Musique) was created in 1669. For 2026, the company also have Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s 1693 opera Médée in their sights.

At the end of our conversation, we return to recitative, to French and Italian declamation. When Marin Mersenne published his Harmonie Universelle, contenant la théorie et la pratique de la musique in Paris in 1636, he wrote that when Italians perform opera the singers seemed to be affected as if really effect of the character. This felt very strange to the French, as their expression was more square, and predetermined, and there was a lot that you could not do. The French view was that you needed to dominate your passions.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Mozart in 1774: Samantha Clarke, Jane Gower, The Mozartists, and Ian Page on stylish form at Wigmore Hall – interview

- Vigour, energy & joy: A Choral Celebration of Queen Mary II from choirs of Royal Hospital Chelsea & Old Royal Naval College – concert review

- A neglected gem revived: New Sussex Opera in Lampe’s The Dragon of Wantley combining historic style and 1980s politics – opera review

- Lobesgesang: Mendelssohn’s rarely performed symphony-cantata is a fine climax to Sir Andras Schiff and the OAE’s exploration of the composer’s symphonic music – concert review

- Fear no more: Brindley Sherratt on releasing his first recital disc – interview

- A German in Venice: Schütz alongside music he could have heard in Venice, a wonderfully life-affirming disc – record review

- Attention must be paid: the Engegård Quartet at Conway Hall in Mozart, Bartok, Maja Ratkje, and Fanny Mendelssohn – concert review

- Opera as it ought to be: Mozart’s Don Giovanni from Hurn Court Opera reviewed by James McConnachie – opera review

- Leeds Lieder 2024

- A Leeds Songbook and a showcase performance: Leeds Lieder Young Artists 2024 – concert review

- A day of French song with a focus on Fauré, with Graham Johnson making us love the composer’s late period, and James Gilchrist in fine form – concert review

- Engaging the audience: James Newby and Joseph Middleton in a folk-inspired programme at a cool Leeds café/bar – concert review

- The sound of an image: recent chamber music by New York City-based, Puerto Rican-born composer Gabriel Vicéns – record review

- A City Full of Stories: Anna Phillips on her work with Academy of St Martin in the Fields’ SoundWalk – guest posting

- Home