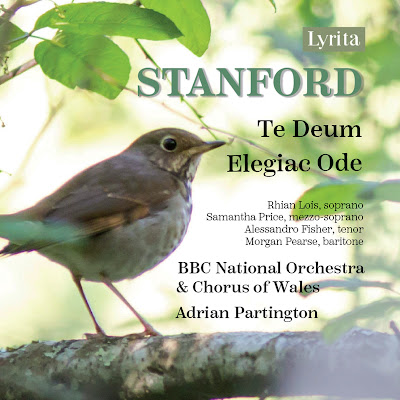

Charles Villiers Stanford: Te Deum, Elegiac Ode; Rhian Lois, Samantha Price, Alessandro Fisher, Morgan Pearse, BBC National Orchestra & Chorus of Wales, Adrian Partington; LYRITA

Reviewed 23 July 2024

Written 35 years before his pupil Holst’s Ode to Death, Stanford’s Whitman setting of the same text shows a young composer willing and eager to explore different avenues

The list of British composers who set the verse of Walt Whitman is fairly well known, Delius, Holst, Vaughan Williams, Hamilton Harty and Bliss. The poetry’s combination of transcendentalism, realism, a religious mysticism unconstrained by the western focus of Christianity, and its free prose offered composers an alternative to the standard canon of English verse. This list covers the years 1899 (for Holst’s earlier essay) to the 1930s (for Bliss’ Morning Heros and RVW’s Dona Nobis Pacem) but there were others too. Charles Wood set Whitman in songs during the 1890s and even more fascinatingly, Charles Villiers Stanford set a whole chunk of Whitman in his Elegiac Ode of 1884.

This new disc from Lyrita features Stanford’s Elegiac Ode, Op. 21 and Te Deum, Op. 66 performed by the BBC National Orchestra & Chorus of Wales, conductor Adrian Partington with soloists Rhian Lois, Samantha Price, Alessandro Fisher and Morgan Pearse.

We begin with Stanford’s Te Deum, his first essay of a large-scale concert setting of the text (his previous settings had been liturgical). Written for the Leeds Festival and performed in 1898, the work was both a celebration of Queen Victoria’s 60 years on the throne and of the 350-strong Leeds Festival Chorus. The work is large-scale and opulent, but it is the chorus that shines forth. Stanford had already premiered his Requiem in Birmingham the previous year, he had conducted Berlioz’s large-scale concert Te Deum whilst Dvorak’s essay in the genre, written for America in 1892, had been performed in London in 1896. However, Stanford manages to avoid the bombast of Sullivan’s Festival Te Deum, written for vast forces for the Crystal Palace in 1872 and featuring an extra brass band.

Though Stanford’s work uses four soloists, it is the vigorous and opulent choral writing that strikes you. And though there can be an Italianate feel to Stanford’s writing, I was reminded also of the open textures and vigour of Dvorak’s setting. This very much true of the glorious first movement, where we are clearly praising God with vim and vigour. The second movement is more intimate thanks to Stanford’s focus on the solo quartet, and for all the strength of the vocal writing, the lyrical nature of Stanford’s gift really comes over. In his booklet note, Jeremy Dibble describes the third movement, ‘Judex crederis’ as the scherzo, it is vivid and full of colour and movement, the use of soloists and chorus being rather operatic. The opening of the fourth movement, ‘Per singulos dies’ gave me hints of Verdi (discuss!). We are back to the soloists here, and the sense of an opera in disguise. Things become more interestingly dark in the fifth movement, ‘Miserere nostri’, whilst the final movement returns us to choral vigour.

Written for the Norfolk and Norwich Festival, Stanford’s Elegiac Ode was his first mature foray into writing for a major British choral festival, though by this date 32-year-old Stanford had written two symphonies, three operas, and major chamber works. The words come from Whitman’s elegy, When lilacs in the dooryard bloom’d, written in the aftermath of President Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 and the contemporaneity of Whitman’s prose rather bewildered critics. Stanford’s pupil, Holst, would use the same text for his Ode to Death, whilst another pupil, RVW’s Whitman set Sea Symphony uses a pair of soloists, soprano and baritone, just as Stanford does in the Elegiac Ode. Stanford divides the work into four movements, creating effectively a symphonic structure, which is intended to be played without a break, the two middle movements shorter than the outer.

Whilst there is no doubt of the Britishness of the music, from the opening notes the sense of Brahms’ major choral settings hovering over the music is palpable, sometimes just a hint, sometimes more clearly. And the way Stanford uses the orchestra, this is a clearly a symphonic work with chorus. The second movement ‘Dark Mother’ is a lyrical and flowing baritone solo that more firmly establishes the Britishness, whilst the third movement, ‘From me to thee glad serenades’ uses soprano solo and female chorus in a rather engaging way that is a world away from 20th century Whitman settings. The final movement, ‘The night is silence’ returns us to the chorus, and to the complex web of Stanford’s inspirations. The hushed sense of suspension he achieves at the opening seems to look forward to the music of his pupils.

The performances on the disc have a sophistication and vigour that does full justice to the music. Adrian Partington marshals his large-scale forces admirably, and all concerned make a real case for this music. The disc fills in a valuable gap in the Stanford discography, but more importantly points to a composer whose choral inspirations were a world away from the British tendency to equate large-scale choral works with religion and Biblical texts.

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) – Te Deum, Op. 66 (1898) [45:24]

Charles Villiers Stanford – Elegiac Ode, Op. 21 (1884) [27.12]

Rhian Lois (soprano)

Samantha Price (mezzo-soprano)

Alessandro Fisher (tenor)

Morgan Pearse (baritone)

BBC National Orchestra & Chorus of Wales

Adrian Partington (conductor)

Recorded 4-5 May 2023 at BBC Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff

LYRITA SRCD 435 3 1CD

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- A vividly realised recording: rediscovering music by Latvian-American composer Gundaris Pone – record review

- Returning to Northern Ireland Opera for his third role, British-Ukrainian baritone Yuriy Yurchuk on Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin – interview

- Relentlessly entertaining: Handel’s Acis and Galatea at Opera Holland Park rather over-eggs things but features finely engaging soloists – opera review

- Contemporary contrasts: Wolf-Ferrari’s Il segreto di Susanna & Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci in a satisfying double bill at Opera Holland Park – opera review

- A sound world that is distinctive, appealing & engaging: Maria Faust’s Mass of Mary on Estonian Record Productions – record review

- A rich sophistication of thought running through this programme that seems worlds away from the typical debut recital: Awakenings from Laurence Kilsby & Ella O’Neill – record review

- Fine singing and vivid character: a revival of John Cox’s vintage production of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro at Garsington – opera review

- An intuitive abstract Sudoku working with sound parameters and with no single solution: Chilean composer Aníbal Vidal on writing music – interview

- Youth, experience and a warm reception: our visit to the Glasperlenspiel Festival in Tartu, Estonia – concert review

- Sustainable Opera for the Future by Max Parfitt of Wild Arts – guest article

- As vivid and vigorous as ever: David McVicar’s production of Handel’s Giulio Cesare returns to Glyndebourne with a terrific young cast – opera review

- Home