From our resident reviewer:

The Russian-Ukrainian choreographer Alexei Ratmansky is a divided soul. In February 2024, he created “Solitude”, to two movements from Mahler symphonies, for New York City Ballet. In February 2025, he made, for the same company, “Paquita”, to nineteenth-century ballet music by Ludwig Minkus and other ballet-specialist composers, incorporating older choreography by Marius Petipa and George Balanchine. The two works are startlingly dissimilar: “Solitude” is poignant, sombre, grief-laden, elegiac, desolate, modern; “Paquita” is ebullient, bright, celebratory, traditionalist, virtuoso, ceremonious, period.

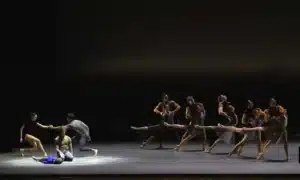

Although the first half of “Solitude” is set to the funeral march of Mahler’s first symphony, the dynamics of Ratmansky’s choreography exist outside that march with a deliberate irony: much more abruptly marcato than its fluency. We can’t help but feel that mourning keeps these people outside any music, however close it comes to expressing their grief. This dance is for a number of characters, notably the mature ballerina Sara Mearns and the young beauty Mira Nadon – but motionless throughout it are one kneeling man (Joseph Gordon, an Adonis now in his prime), with the lifeless body of a boy beside him.

The second half is to the renowned Adagietto of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. Here, too, the music exists in ironic separation from its music: Mahler’s fanously luninous composition is all flow, with scarcely any apparent pulse, but Ratmansky’s choreography has edges, sharp metres, jumps, pounces. Gordon dances with an adagio beauty scarcely known since the prime of Anthony Dowell in the 1970s, with marvellously flowing physical lines (the lines very often flow downwards, arabesque penchées in ballet terminology) – and yet he and the music exist as much in opposition as in harmony.

After two viewings of the strange musicality or anti musicality of this ballet, I find that It conveys very remarkable kinds of lyrical alienation and isolation. And its isolation from its music is part of the numbed eloquence it demonstrates. You watch it as if cut off from it. But then that’s what it shows: humanity that’s sundered, by the mourning process, from other humanity.

After his solo, Gordon dances with the boy, a dance student (Ethan Schmidt at the last performance I saw). We may feel this character is Gordon’s son – but we may also feel he is Gordon’s younger self. He dances as if learning from Gordon; both he and Gordon are compelling but remote from us. Are they ghosts? Is Gordon a father forever sundered from humanity by the loss of his son?

Other dancers join them; the Adagietto continues, expressing a rich sensuousness that connects to the dancers’ mood of mourning even while the dancers never share its warmth or luxuriance. There is no resolution.

In “Paquita”, by contrast, the dancers are on the music, in the music, with the music. Probably most of the dances are by Petipa and Balanchine, with Ratmansky as their editor. (It’s probable that Balanchine, author of the opening pas de trois, was himself editing Petipa dances he had known in Russia; and it’s at least possible that Petipa, in 1882, was editing choreographic ideas by Joseph Mazilier, who in 1846 had made an earlier “Paquita”. Other cooks may have also contributed to the recipes here.) Ratmansky takes these dances at fast tempi; he doesn’t let his dancers luxuriate as has become the norm in recent Russian and French renditions of “Paquita”.

There are no fewer than nine solo variations, seven for women, with high-exposure pointwork. Like a jeweller, Ratmansky shows us phrases of Petipa-type steps in gorgeous clusters. When balletomanes look closely, they’ll see how Ratmansky is showing us several “Paquita” solos that feel familiar but that turn out to be wonderfully lucid and unfamiliar. It’s truly hard to believe this is the man who gave us “Solitude”. But elusiveness has been the core characteristic of the Russian-Ukrainian-American Ratmansky’s whole career. You think you know me? Oh, no, you don’t!

These “Paquita” divertissements are vehicles to challenge and to showcase dancers. The young Mira Nadon was cool, elegant, and glamorous in the prima role – the ice that burns. Gordon, no less elegant and glamorous, was captivating brilliant as her partner. (In another cast, young Roman Mejia was heroic.) Amid supporting solos, the jubilantly strong Emily Kikta was irresistible; Alexa Maxwell was a marvel of outgoing lucidity. Mia Williams, a name new to me, was distinctive, as was David Gabriel; and Domenika Afanasenkov was something more – a really haunting young dancer with melting beauty amid the splendour. Ratmansky is the kind of choreographer who can make you like dancers whom you’ve hitherto failed to see the point of: with Erica Pereira, whom I’ve observed since 2007 but seldom with much pleasure, he makes her seem entertainingly eloquent rather than just an ego.

Founded in 1948 by choreographer George Balanchine and impresario Lincoln Kirstein, New York City Ballet has always been the world’s most valuable ballet company. (I’m not the first tai call it this.) The many dozens of modern classic ballets created for it by Balanchine include “La Valse”, “Agon”, “Jewels”, “Duo Concertant”, “Symphony in Three Movements”, “Stravinsky Violin Concerto” – works that long ago entered international repertory. Jerome Robbins made for it such works as “Afternoon of a Faun”, “The Concert”, “Dances at a Gathering”, “In the Night”, and “Glass Pieces”, which are also danced globally by other companies today. This century, ballets now also danced all round the world – “Russian Seasons”, “Concerto DSCH”, and Pictures at an Exhibition” by Ratmansky, “Polyphonia” and “After the Rain” by Christopher Wheeldon, “Year of the Rabbit”, “In Creases”, “Rodeo: Four Dance Interludes” and “Everywhere We Go” by Justin Peck – were created for this same City Ballet. Wheeldon was resident choreographer here in 2001-2008. (He is now based in his native Britain, making far more glossily conventional work.) Peck, California-born, has been this company’s resident choreographer since 2014. The Russian-Ukrainian-American Ratmansky, who began to create on City Ballet in 2006, became its Artist in Residence in 2023. (City Ballet also commissions new ballets from many other choreographers, though its gates have been barred to most other white male dance-makers in recent years.)

The company’s repertory pours forth fabulously in a spring season. In seventeen days, I’ve caught twenty different one-act ballets, most of them several times. Though some Balanchine nuances have certainly been lost over the decades, most of these dancers still show more fulfilment and poetry in Balanchine’s ballets than anywhere else. One performance of his Mozart “Divertimento no 15” (Saturday 10) had a lustre not matched since the year of his death. In this pure-dance ballet that seems the quintessence of civilisation and sophistication, qualities of the sublime also shone through.

(c) Alastair Macaulay

The post Alastair Macaulay finds Mahler alienation in New York appeared first on Slippedisc.