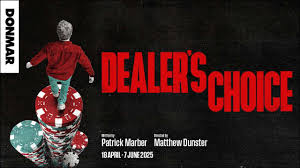

From our critic in residence, Alastair Macaulay reviews Patrick Marber and Mark Ravenhill: “Dealer’s Choice” and “Ben and Imo”.

The abiding subject of the playwright Patrick Marber is masculinity: which, for him, includes male bonding, masculinity as role-playing, and men’s need (chiefly in non-sexual ways) of other men. All this is enduringly present in his first play, “Dealer’s Choice”, new thirty years ago (February 1995) at the National Theatre as directed by Marber himself. (Other Marber plays deal with the myriad effects of masculinity on women.) The play has six male characters, no female. It also has psychological depth, considerable comedy, and suspense. Nobody dies, but it’s often on the borderline of tragedy – of insolubly painful aspects of human nature.

The play concerns an evening of poker playing. At its core – though we only gradually discover this – is the father-son relationship of Stephen and Carl. If memory serves, Daniel Lapaine and Kasper Hilton-Hille play Stephen and Carl with less macho force and danger than Nicholas Day and David Bark-Jones did in the original cast, yet just as effectively. It’s fascinating to find that, even as the play is inevitably becoming a period piece, it works no less well

Probably you could stage it with minimal changes as a play about six women – but that would ring far fewer bells. Our world speaks too little about compulsive female gamblers, whereas, throughout Dealer’s Choice”, we constantly see how our society has long accepted men’s need to gamble on an intimate, clubbish, level.

The new production at the Donmar Warehouse, directed by Matthew Dunster, isn’t the play’s first return to the West End. It’s fair therefore to feel that “Dealer’s Choice” is a classic; it’s fair to hope it will still be seen as such in the far distant future.

But the first and finest way in which you feel Marber’s mastery is his rhythm. Listening to “Dealer’s Choice”, I remember how the director Peter Hall liked to rehearse his plays like a conductor, establishing – from Shakespeare to Pinter – qualities of pulse, momentum, rubato and more. Marber has often shown the finest dramatic rhythm of any modern playwright: how good in “Dealer’s Choice” to feel it again. Matthew Dunster, directing, catches that from the first.

The biggest change from the original is that, as the essentially comic character Mugsy, Hammed Animashaun is so fabulously but naturally larger-than-life that he almost upends the play. Almost but not quite: the way that Carl speaks about the absent Mugsy to Stephen now has a quality of inevitability: they feel how he brightens their lives when he’s gone.

Brendan Coyle brings qualities of quietly dangerous weight to the professional gambler Ash. When he’s winning, that, too, seems inevitable. When he’s losing, that becomes another of the play’s startling turns of the screw. Alfie Allen (Frankie) and Theo Barklem-Biggs (Sweeeney), already vivid, will probably play their parts with more bite as the run continues.

More prolific than Marber, Mark Ravenhill also emerged in the mid-1990s. Marber’s male characters are more likely to be straight, Marber’s to be gay, but the main difference between them is stylistic. Ravenhill’s writing seldom has the amazing mastery of rhythm that makes Marber such a master; but Ravenhill, since “Shopping and F*ching”, has been more of a sociologist.

His “Ben and Imo”, however, is atypical. It has just two characters – Benjamin Britten and Imogen Holst – and the setting is the coastal town of Aldeburgh, far from the madding crowd and often with the sea playing an audible part. The play covers a few months in 1952-1953, during the gestation of Britten’s Covent Garden Coronation season opera “Gloriana”: Imogen Holst arrives as the assistant Britten needs. And his needs are great, since “Gloriana”, far from comfortable Coronation fare in its coverage of Elizabeth I’s relationship with Essex, takes Britten far from his own previous kinds of drama . But Imogen Holst – the hearty but unworldly daughter of another renowned British composer, skilled in directing choral work and in the dances of the Elizabethan period in which “Gloriana” is set – does bring singular gifts to their collaboration.

“Ben and Imo” began life as a radio play in 2013, Britten’s centenary year. Last year, Ravenhill adapted it as a stage play for the Royal Shakespeare Company, which has been presenting it as “The true story of the passionate partnership between Benjamin Britten and Imogen Holst.” Erica Whyman directs: Samuel Barnett is Britten, Victoria Yeates is Holst. Barnett – never to be forgotten as Posner, the gay member of Alan Bennett’s original History Boys in 2004, (I wish I had seen him as Carl in the 2007 Menier Chocolate Factory production of “Dealer’s Choice”) and superb in 2022-2023 as the solo performer of Marcelo Dos Santos’s “Feeling Afraid as If Something Terrible Is Going to Happen” – is wonderful, and wonderfully convincing, as Britten. Both creative energy and his bottled-up Englishness are brilliantly evident in his body language and his speech patterns. Victoria Yeates, not least in the verve and detail of her period dances, is an

Imogen Holst to match him in theatrical essence.

She is, however, increasingly shrill in too many scenes, a quality that makes her unbelievable as the historical Imogen. And, even if the RSC has marketed this as the “true” Britten-Holst story, there are ways in which “Ben and Imo”, terrifically enjoyable, is in several ways unconvincing and untrue. Do you believe, in the big quarrel between Imo and Ben in Act Two, that Britten would ever address Imogen as a “cunt”? Even Barnett can’t persuade me of this. And it’s simply silly and lazy of Ravenhill to make Britten claim that Frederick Ashton, with whom Ravenhill’s Britten says Ninette de Valois is trying to make him work, is a “stranger” to him. It wouldn’t have taken much homework on Ravenhill‘s part to find that Ashton had directed the world premiere (at Glyndebourne) of Britten’s opera “Albert Herring” in 1947.

In life as in the play, Britten won the fight for the production for the big 1953 Covent Garden Coronation gala – the premiere of “Gloriana”. Yet Ravenhill gives us no sense of that Coronation season at that opera house, which commissioned other premieres, other composers, and performers led by Maria Callas and Margot Fonteyn. Ravenhill doesn’t even bother to tell us that Ashton, who had been resident choreographer at Covent Garden since 1946, choreographed the world premiere of a score by a more conventional younger composer, Malcolm Arnold, with a cast led by Margot Fonteyn and Beryl Grey, with a premiere six days before that of “Gloriana”. Covent Garden chose instead to give the big gala evening to Britten’s problematic premiere, but that’s history of a kind with which Ravenhill doesn’t concern himself.

Alastair Macaulay

The post Alastair Macaulay reviews: Two plays about masculinity (Including Britten) appeared first on Slippedisc.