The Royal Opera’s “Jenufa”

By Alastair Macaulay

Leoš Janáćek’s opera “Jenůfa” – one of the great works of the human spirit – takes a tragic situation, deepens it, and then transcends it. The unmarried Jenůfa is made pregnant by one man, Śteva, and has her face slashed by another Laca, whose love for her drives him to this shocking violence. After she gives birth to her baby in secret, Śteva firmly refuses to marry her – whereupon her passionately religious and orthodox stepmother, the Kostelnička, ends the baby’s life, which she deems doomed, by burying it in the ice of the frozen mill-stream. The tragic elements of this story do not end there, but what amazes is how Jenůfa and Laca rediscover love as the opera end, in a final scene of such tenderness that I always feel as if tears are flowing down my face throughout it.

In Janáček’s music, romanticism meets modernism: folk elements are put under intense strain and fragmentation. The unconventional story of Jenůfa is set against the reactions of a conventional village community; we feel the drama in musical terms. And when the ending arrives, with its many threads of reconciliation, forgiveness, and recessional, it’s buoyed by elements of lyrical sweetness not heard before in this work but related to the largeness of spirit often heard in earlier scenes.

Jakub Hrůśa, the Royal Opera’s music director designate (he starts in autumn 2025), is a Czech conductor here in his native musical terrain (as he was when conducting the Czech Philharmonic at the Albert Hall Proms last August). From the opening bars, he draws us into the very particular wind and percussion sound effects that make “Jenůfa” so singular, even amid Janáček’s output.

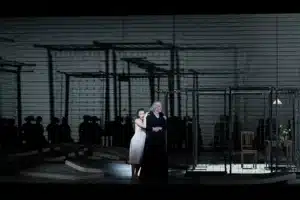

At Covent Garden, Claus Guth’s 2021 production has been lucidly revived by Oliver Plath. There are a few gratuitous production elements – notably the predatory human-size crow that menaces the lair where the Kostelnička guards Jenůfa and her newborn child – that detract more than they add, but the many tensions within the opera are made vivid.

The cast features singers who have long been part of the British opera scene (Jonathan Lemalu as the Mayor and Marie McLaughlin as the Mayor’s Wife) as well as the younger Nicky Spence as Laca and Thomas Atkins (Śteva). Let’s hope this shows a new emphasis on British and house-trained singers under Hrůśa’s regime. Spence in particular showed new qualities of virile vulnerability.

As Jenůfa, the American soprano Corinne Winters shows both how difficult Janáček’s vocal writing can be – it travels between lower and upper registers with a certain awkwardness – and how rewarding that awkwardness can become. You hear both the unpolished facets of Jenůfa’s character and then her soaring elements of release. And in her acting you see how she’s both demure and desperate.

Earlier this century, Karita Mattila was a Jenůfa of note. Like several other Jenůfas, she has moved onto the role of the Kostelnička. She’s long been an important singing actress; she sometimes overacts too. You can see moments when she too visibly relishes the Kostelnička’s anguish; but those moments pass, while her sheer authority never fails. We keep changing our mind about this character, as we do about all the dramatis personae in this perennially rewarding masterpiece.

The post Alastair Macaulay’s review: Jenufa never fails appeared first on Slippedisc.