|

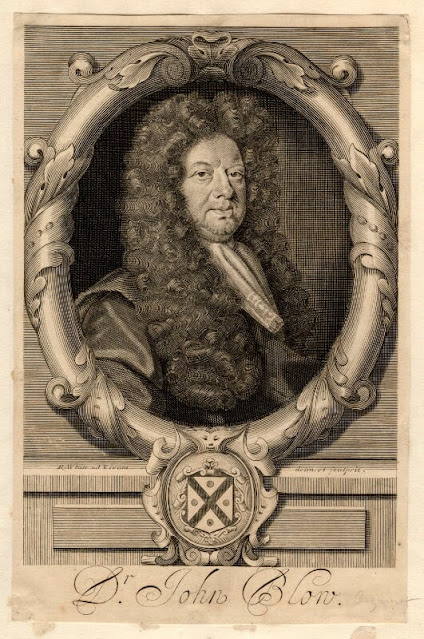

| John Blow by Robert White, line engraving, published 1700 NPG D1075 © National Portrait Gallery, London |

Purcell: Welcome to all the pleasures; Raise, raise the voice, Blow: An Ode on the Death of Mr Henry Purcell, Hall: Yes, my Aminta, ’tis too true, Draghi, Croft; Jessica Cale, Samuel Boden, Nicholas Mulroy, Chris Webb, Dunedin Consort; Wigmore Hall

Reviewed 18 November 2025

Blow’s fabulous Ode for the death of Purcell given its due in a programme that explored Purcell’s later music alongside that of his contemporaries and friends in performances that engaged and delighted

In 1695, John Blow and Henry Purcell published Three Elegies Upon the Much Lamented Loss of our Late Most Gracious Queen Mary as a shared homage. By the end of the year, Purcell would be dead at only 36 and Blow, some ten years Purcell’s senior, would resume his post as Organist at Westminster Abbey which he had relinquished in favour of his talented pupil.

In 1696, Henry Playford published Blow’s Ode on the Death of Mr Henry Purcell, ‘Mark how the lark and linnet sing’. The Ode set a poem by John Dryden, one of Purcell’s favourite collaborators, and twelve poems in Purcell’s honour were produced; of these, at least five inspired musical settings. These include works by Daniel Purcell (setting another Henry Purcell collaborator, Nahum Tate), Godfrey Finger, Jeremiah Clarke and Henry Hall.

Blow’s Ode on the Death of Mr Henry Purcell and Henry Hall’s own tribute, Yes, my Aminta, ’tis too true formed the centrepieces of the Dunedin Consort‘s concert at Wigmore Hall on 18 November 2025. Purcell died on the eve of St Cecilia’s Day so it was appropriate that the concert included two of his St Cecilia odes, Welcome to all the pleasure from 1683 and Raise, raise the voice (c. 1685). Along with these there were instrumental pieces by Purcell, Giovanni Draghi and William Croft. The performance was directed by tenor Nicholas Mulroy (Dunedin Consort’s Associate Director) who was joined by Jessica Cale (soprano), Samuel Boden (tenor), and Chris Webb (bass) with the instrumentalists Matthew Truscott and Huw Daniel (violin), Thomas Kettle (viola), Jonathan Manson (cello), Laszlo Rozsa and Olwen Foulkes (recorder), Toby Carr (theorbo) and Stephen Farr (organ).

In terms of length and musical complexity, Blow’s Ode on the Death of Mr Henry Purcell is a substantial piece but it uses compact musical forces: two voices, two recorders and continuo, the use of recorders leaning into the instrument’s association with mourning. The voices intended were probably high tenors, as here, singing full voice lightly with some falsetto: what the French termed haut-contre. For the post-War revival of music by Purcell and his contemporaries we got used to hearing this music sung by modern countertenors and the change in sound world can be remarkable.

Blow’s piece came at the beginning of the second half of the concert. The recorders brought a sober, lyric melancholy sound to the music then over them came the intertwining voices of Samuel Boden and Nicholas Mulroy. The two voices contrasting with Boden’s lighter and shading into falsetto for this high-lying passages with Mulroy’s no less fluent yet remarkably vibrant. The opening duet was substantial, in two sections with both singers having remarkable decorations applied over the substantial instrumental writing. The middle three solo sections, two for Mulroy one for Boden were in contrast to the duets in that they were declamatory yet by turns touching, vigorous and elaborate. The final duet, again in two sections, was equally powerful and moving. This was supremely intimate and personal music, the forces required suggesting small-scale, almost private performance. Dryden’s words are in no way bathetic (thankfully) and both singers’ diction was excellent so that music and word counted. The Ode was preceded by Purcell’s Overture in G minor Z772 (c1682) for recorder and strings, the presence of the recorder bringing out the grave, tragic feel of the opening, and even in the lively second part the music veered towards melancholy.

The first half had ended with Henry Hall’s own tribute to Purcell. Henry Hall (c1656-1707) had been a chorister in the Chapel Royal alongside Purcell and would be organist of Hereford Cathedral. His Yes, my Aminta, ’tis too true also used recorders and continuo with soprano and bass solos (Jessica Cale and Chris Webb). Hall set his own text which leaned into the pastoral associations of the recorder by creating a dialogue between a shepherd and a shepherdess about the death of Daphnis (Purcell).

First there was another overture by Purcell, this time in D minor and a remarkably rhythmic yet serious work. Hall’s piece opened with a sober, lyrically attractive solo for Web where the writing for recorder was substantial, creating a remarkably complex, serious piece where the instrumental writing continued in a ritornello after the singer. The subsequent movements formed a sort of lyrical dialogue, the arioso-like recitative performed just with continuo, and Hall did not shy away from bringing ornamentation and elaboration into the vocal lines. We had a moment of vivid vigour in Webb’s dance-like solo ‘But when he served up his theorbo to arms’ but overall the mood was lyric melancholy ending with a most appealing duet which saw the return of the recorders.

It was also something of a novelty to hear such a long sequence of substantial music for recorders. Too often, even in Baroque music, the instrument is brought in as a bit of local colour or when the heroine starts singing about birds. Here, Laszlo Rozsa and Olwen Foulkes displayed the instrument’s serious contrapuntal chops.

The evening began with Purcell’s 1683 St Cecilia Ode, Welcome to all the pleasures. After a symphony which moved from the elegantly graceful to something energetic, the opening section featuring all four soloists proved wonderfully direct and communicative. Christopher Fishburn’s words are, admittedly, somewhat trivial but what Purcell does with them elevates. In ‘Here the Deities’, Samuel Boden’s high tenor unfolded elegantly over the ground bass, and then after a vigorous, dance-like ensemble movement, Nicholas Mulroy brought out his own sense of elegant phrasing in ‘Beauty though Scene of Love’, the ending of this movement was touching but the finale was all vigorous vigour and dance.

Then came a pair of works by Purcell’s contemporaries. John Blow’s Chaconne in G from around 1680 began in an engagingly lively manner and developed into something remarkably vigorous. This chaconne would doubtless have left the dancers somewhat breathless. It was followed by the Trio Sonata in G minor by Giovanni Draghi (c1640-1708), one of the many Italian drawn to London by the prospect of earning a good living. His five-movement work succeeded in creating a very particular atmosphere, the opening Adagio featured sustained violin lines interweaving over striking harmonies, the whole having an intimate feel, and this returned in the third movement Adagio. In between was a lively Canzona, and the work ended with a graceful, swaying minuet and lively finale, yet the opening material made a return at the end.

In the middle of the second half we had further instrumental delights with William Croft’s Sonata in F a three movement work that used both strings and recorders and for most of the piece Croft delighted us by using his forces in dialogue. Thus the whole work function as some sort of dialogue duel, by turns lively and gentle, between violins and records. All in all, a complete delight. Croft is another chorister from the Chapel Royal. Younger than Purcell, he too was taught by Blow, became Blow’s successor and is bet known for his Funeral Sentences.

The evening ended with Purcell’s Cecilian ode Rise the voice. This sets a rather trivial, anonymous text and Purcell’s forces are very stripped back, just soprano (Jessica Cale), tenor (Nicholas Mulroy) and bass (Chris Webb) with violines and continuo, yet the work is full of Purcell’s imagination. The opening section threatened to be rather grand, yet the music followed the sense of the words with some lovely intimate writing on ‘Let the sweet lute its softest notes display’. A lilting solo for Cale continuo accompaniment might have been intimate but the vocal writing did not shy away from elaboration. The ensemble ‘Crown the day with Harmony’ again brought out contrasts in the music, and then there was a lively solo over ground bass for Cale where her engaging manner made light of the music’s elaborations. The final ensemble movements were lively indeed, suggesting an almost raucous element of celebration.

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- A real radio opera: Claire Booth as a pianist labouring under the absurdity of life under Stalin in Joe Cutler’s Sonata for Broken Fingers – record review

- Youthful & engaging with relish for text & drama: Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea from HGO at Jacksons Lane Theatre – opera review

- The Life and Loves of Sarah Teasdale explores contemporary American late-romanticism at London Song Festival – concert review

- The Rain Keeps Coming: Amelia Clarkson, the youngest female composer commissioned by the Ulster Orchestra, on her new work for them – interview

- Poetic exploration: Ensemble Près de votre oreille in an engaging exploration of chamber & vocal music by William Lawes – record review

- The other brother: music by Galileo Galilei’s younger brother on this lovely new EP – record review

- Fascinating, distracting & frustrating: Janáček’s Makropulos Case gets its first production at Covent Garden in Katie Mitchell’s farewell to opera – review

- James Blades: Pandemonium of the One-Man Band, James Anthony-Rose on his new music theatre piece on the great percussionist – interview

- A new solo album from British pianist, Alexander Ullman, features a thoroughly enjoyable selection of music by Edvard Grieg – record review

- Home

.jpg?w=670&resize=670,446&ssl=1)