|

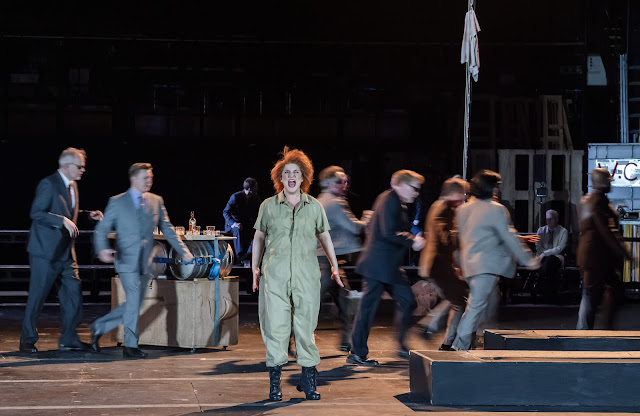

| Brecht & Weill: Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny – English National Opera (Photo: Tristram Kenton) |

Brecht & Weill: Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny; Rosie Aldridge, Kenneth Kellogg, Mark Le Brocq, Simon O’Neill, Danielle de Niese, director: Jamie Manton, conductor: André de Ridder; English National Opera at the London Coliseum

Reviewed 16 February 2026

Brecht and Weill’s fascinating but problematic work in an evening that combined high-energy performance and Brechtian Epic Theatre but was let down by the challenge of performing it in the London Coliseum

Brecht and Weill’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny might be an iconic work, but it remains tricky to perform and bring off in the theatre. English National Opera last performed it in the 1990s in a production directed by Declan Donnellan [see the review in The Independent], whilst Covent Garden essayed the work in 2015 [see my review]. Now, ENO has chosen the work as a showcase for the talents of conductor André de Ridder, the company’s incoming music director.

With just three performances at the London Coliseum, opening on 16 February 2026, this was very much blink-and-you’ll-miss-it theatre, but Jamie Manton‘s stripped back production, designed by Milla Clarke, was clearly intended to be high-energy, leaning into the idea of Brechtian theatre.

Rosie Aldridge was Begbick with Kenneth Kellogg as Trinity Moses, Mark Le Brocq as Fatty the Bookkeeper, Simon O’Neill as Jimmy Macintyre, Alex Otterburn as Bank-Account Billy, Elgan Llŷr Thomas as Jack O’Brien, David Shipley as Alaska Wolf Joe, Danielle de Niese as Jenny Smith, and Zwakele Tshabalala as Toby Higgins. Lighting was by D.M.Wood, and choreography by Lizzi Gee. Sound design was by Jake Moore.

|

| Brecht & Weill: Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny – Adam Taylor (dancer) – English National Opera (Photo: Tristram Kenton) |

Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny is a strange work that encompasses much of the working relationship between Brecht and Weill. They began work on it before Threepenny Opera, and Brecht’s third version of the libretto, which he published, was far more aligned to his Marxist principles and helped to create the breach with Weill. Weill’s music skitters all over the place, from the cabaret-style songs originally written for the Mahagonny Songspiel, to more operatic numbers, to Weill in full symphonic mode. It was a time when Weill was experimenting with all types of musical theatre, and Mahagonny can be seen as something of a transitional work. This, and the work’s history, make finding a performance style difficult.

Written for the opera house, it premiered in Leipzig, with a cast of opera singers. A revised version was produced in Berlin with Lotte Lenya as Jenny only because, in the edgy political climate following the Nazi Party’s rise to power, no opera house would perform it. Following the Anschluss, the score was lost and one only surfaced in the 1950s. This was recorded by Lenya as Jenny, very much as a singing actress purely out of necessity as Lenya knew that if she didn’t perform the work, no-one else was going to. (Also bear in mind that the post-War Lenya was a chanteuse with a voice in the low contralto range, whilst the pre-War Lenya had been a soubrette soprano!).

At the London Coliseum, the performance really leaned into the music theatre aspects of the piece. Microphones were very much in evidence, with Danielle de Niese sometimes crooning Jenny’s songs. The set was simply a wide open stage with a large container that doubled as virtually everything from a knocking-shop to the venue for Jack O’Brien eating himself to death.

.jpg) |

| Brecht & Weill: Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny – Danielle de Niese, Simon O’Neill – English National Opera (Photo: Tristram Kenton) |

The production might have had aspirations to Brechtian Epic Theatre, but director Jamie Manton took care to ensure that he was telling a story. This Mahagonny was a bit grim and rather a hole-in-the-corner sort of place, which works. Lavish production values the opera does not need. But performing this music on the wide open spaces of the London Coliseum stage presents something of a challenge. With no real set to form a backdrop and aid the singers, the balance was not always what it could have been. With the cast delivering what was clearly a high energy performance, I rather longed for the production to have been given in a somewhat smaller, more sympathetic venue.

Rosie Aldridge, Kenneth Kellogg and Mark Le Brocq made Begbick, Trinity Moses and Fatty rather into ringmasters, corralling the other putative citizens of Mahagonny. A rather apt metaphor, but it meant that the three singers sometimes rather disappeared into the crowd. Aldridge in particular brought a real edge to her performance that was a great benefit here.

|

| Brecht & Weill: Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny – Rosie Aldridge – English National Opera (Photo: Tristram Kenton) |

Jenny Smith has some of the work’s best known numbers, and Danielle de Niese certainly worked the sexy angle and delivered the songs with strong music-theatre style, but she also brought real edge to her solo at the end of Act Two when she refuses to help the destitute Jimmy. As Jimmy, Simon O’Neill sang with a heroic sense of line and vibrant, if somewhat insistent, tone. O’Neill managed to bring real pathos to Jimmy’s downfall along with a sense that he had become foolishly fond of Jenny.

Of course, the work punctures all these ideas. That is part of its appeal, the way Brecht and Weill use great, hummable tunes in the service of skewering the ideas of capitalism, romantic love and more. There are some oddities, the Benares Song in Act Three feels almost out of place and thrown in for good measure, but it was admirably performed

Alex Otterburn came to the fore as Billy during the latter part of the opera, almost making the character seem sympathetic. Elgan Llŷr Thomas ate himself to death with wonderful aplomb as Jack, whilst David Shipley’s Joe had the great bad fortune to die in the boxing match.

|

| Brecht & Weill: Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny – Elgan Llŷr Thomas – English National Opera (Photo: Tristram Kenton) |

The six women who arrived with Jenny (Joanna Appleby, Deborah Davison, Sophie Goldrick, Ella Kirkpatrick, Claire Mitcher, Susanna Tudor-Thomas) provided a welcome touch of colour to the proceedings and made Weill’s complex weavings around the Alabama Song seem completely natural. And of course, there weren’t just women, the six good-time girls were accompanied by two rent boys, dancers Damon Gould and Adam Taylor.

The interval was placed after Act Two, which meant that we had quite a long first half at around 100 minutes. This highlighted a drawback with the production, the feeling that the pacing was slow at times. This may have been due to the way the dialogue and sung dialogue was being delivered in order to be comprehensible. But though the pacing of the individual numbers was admirable, overall the second act rather sagged, and I longed for a more intimate, zippier account of the piece.

The work was sung in Jeremy Sams’ witty English translation, though I did miss some of the more familiar lines from the older English versions.

|

| Brecht & Weill: Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny – Kenneth Kellogg, Rosie Aldridge, Mark Le Brocq – English National Opera (Photo: Tristram Kenton) |

In the pit, de Ridder and the orchestra gave a loving account of the work, bringing out the richness of Weill’s score and making the more complex, symphonic aspects of the piece sound all of a whole with the rest.

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- A lightness of touch shot through with seriousness: a new Marriage of Figaro at Opera North with an engaging sense of ensemble – opera review

- The power of the ordinary: Phyllida Lloyd’s wonderful, stripped-back version of Britten’s Peter Grimes at Opera North with John Findon – opera review

- Sky with the Four Suns: we get up close and personal with Manchester Collective in the Crypt at St Martin-in-the-Fields – concert review

- Fantastical & surreal: Thaddeus Strassberger’s vision of Berlioz’ Benvenuto Cellini in Brussels anchored by a heroic performance from John Osborn – review

- Ethel Smyth’s String Trio on Solaire records: Trio d’Iroise draw our focus onto this neglected piece – record review

- Anonymous no more: 16th century works from a choirbook created in Arundel & now residing in Lambeth, given voice for the first time – review

- The Strijkkwartet Biënnale Amsterdam: punching well above its weight to the delight of its admiring international audience – review

- Letter from Florida: Verdi reminds us to grieve for and remember soldiers everywhere. Messa da Requiem from Cleveland Orchestra – concert review

- Home

.jpg?w=998&resize=998,665&ssl=1)

.jpg?w=670&resize=670,446&ssl=1)