|

| Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire – Claire Booth & Nash Ensemble at Aldeburgh Festival, 2024 (Photo: Marcus Roth (c) Britten Pears Arts) |

Soprano Claire Booth and pianist Christopher Glynn have previous when it comes to focusing on composers whose songs deserve to be better known. Recent forays into this repertoire have led them to deep dives into songs by Percy Grainger, Folk Music, Edvard Grieg, Lyric Music, and Modest Mussorgsky, Unorthodox Music. Now they are repeating this with Expressionist Music on Orchid Classics, a disc that explores Schoenberg’s songs beyond that handful that people feel obliged to perform.

|

| Claire Booth (Photo: Sven Arnstein) |

This year is, of course, the 150th anniversary of Arnold Schoenberg’s birth, and Claire is devoting quite a bit of time to the composer. This is not new, she has performed Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire since taking part in a performance directed by Pierre Boulez shortly after she left college and Pierrot Lunaire features on another disc with Ensemble 360 that is being released on Onyx Classics in September, and she will be performing the work several times including at the Aldeburgh Festival [see Tony’s review]. But her musical life extends beyond Schoenberg and this year she is also performing new works by Zoë Martlew and Helen Grime which Claire has commissioned.

Schoenberg’s song-writing spans much of his career from the early 1890s to the 1930s, so they vary in style from his late romantic works to free atonality to twelve-tone. In Expressionist Music, Claire and Christopher Glynn perform songs from his Opus 2 (1899), Opus 3 (1899/1903), Brettl-Lieder (1901), Opus 6 (1903/1905), Opus 12 (1906), Opus 14 (1907/1908), Opus 48 (1933) as well as something from Gurrelieder (1901/1911).

As she points out, some of these songs are known and occasionally performed, but the name of the composer and his reputation seems to prevent performers and promoters from exploring further. With his 150th anniversary, it feels super-important to Claire to be performing his music and she confessed herself somewhat surprised that festivals have not been showcasing his music more.

Her and Christopher Glynn’s booklet note explains their thinking, “the inescapable truth is that a century on, Schoenberg is still not box office. But for anyone who believes that Schoenberg is cold, cerebral and unapproachable, we can only say this: try the songs. Having explored every single one of them (as we did over a few intense days one summer), it’s impossible not to be struck by just how much magnificent music there is to discover, and that is what we have tried to celebrate in this recital.”

Her previous collaborations with pianist Christopher Glynn have involved well-known composers whose vocal works have rather slipped under the radar, so Grieg’s songs are far less known than his piano music and orchestral pieces, whilst Mussorgsky is better known for his big orchestral works, and besides which this disc gave Claire the chance to sing things like the Songs and Dances of Death which are generally seen as the preserve of male (mainly bass) singers. Schoenberg felt like the obvious next step. Schoenberg is, of course, no unknown but lots of musicians and promoters have decided where he fits in the canon and which of his works are programmable. She recalls that at music college, there was so much other repertoire that his songs were not done, and most young singers would not have considered taking Second Viennese School lieder to lieder class (Claire did!)

|

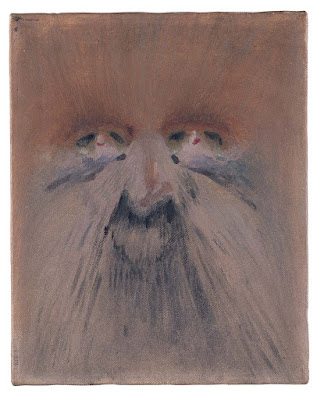

| Arnold Schoenberg: Tears (Image: Belmont Music Publishers, Los Angeles courtesy Arnold Schönberg Center, Wien) |

Some of Schoenberg’s lieder sound like Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler, but then Claire points out that Schoenberg did not jump out as a fully-formed atonal composer. He was never a maverick and his music emerges clearly and logically from the world around him (and it has always struck me that the converse is true also, so there are early Richard Strauss songs that approach Schoenberg). She finds it wonderful to hear how his music can link through to other composers. His song-writing is not just late Romantic or cabaret (notably the Brettl-Lieder) but much else besides. She comments that the Opus 6 songs are very theatrical and remarkably diverse as he sets a range of poets. He also arranged folksongs, and then there is the Opus 14 ballad, Jane Grey (setting text by Heinrich Ammann about the execution of Lady Jane Grey). There is so much to draw on.

The disc is themed on Schoenberg’s paintings, with a group of songs exploring a theme from one of the paintings – Expectation, Flesh, Nocturne, Hatred, Satire, Thinking, Winter Scene, and Tears. Schoenberg’s painting was very much part of the Expressionist movement and Claire points out the fact that he could call a painting Tears or Hatred. She sees Expressionism as trying to mainline emotion, terrific as a creative force with the paintings helping create a narrative arc for the songs on the disc. Painting was the same for Schoenberg as making music, and he revelled how culture could be hybrid. This is something that Claire appreciates and she comments that we seem to be moving away from the 20th century’s focus on celebrity monoculture, the idea that artists concentrate on just one thing.

She hopes that, following on from the disc, festivals will be interested as Schoenberg’s songs deserve to be better known and there are plenty of ways into the repertoire, they are far more than one-colour works. There is deliberately nothing of Pierrot Lunaire on the Expressionist Music disc as the work is completely seminal and it is hard to better it.

Claire performed Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire last year with Ensemble 360 (the ensemble resident at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre), in the round and without a conductor. Pierrot Lunaire is a work she has lived with and performed ever since that first performance with Boulez when she was straight out of college. Last year’s performance seemed to deserve further life, and having lived with the work for what feels like ages, this seemed a good opportunity to record it. The disc, with Ensemble 360, is released on 27 September on Onyx Classics.

But having decided to record Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, there came the question of what to record with it. Having realised that she would like to do some singing on the disc, as opposed to the Sprechstimme used in Pierrot Lunaire, the idea was conceived to look at other manifestations of Pierrot. Whilst the disc does include music by Robert Schumann and Thea Musgrave, its main focus is on works by contemporaries of Schoenberg. Claire sees the popularity of the Pierrot figure to be a manifestation of late 19th and early 20th-century Expressionism. Hard to pin down, it seems to arise from boredom with the status quo and Pierrot is a mask that anyone can put on. It proved easy, in a way, to look at how other composers felt beguiled by the figure. Giraud’s poetry (on which Schoenberg based Pierrot Lunaire) was set by other composers and the disc casts its net widely with music by Korngold, Kowalsky, Joseph Marx, Poldowsky, and Amy Beach.

|

| Albertine Zehme & ensemble after th premiere of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire in 1912 |

As a result of her two recording projects, Claire got to know Randol Schoenberg (the composer’s grandson) a little, and she was intrigued at how keen the Schoenberg estate was. In December, she is going to Vienna to perform Schoenberg’s lieder and will be staying in Schoenberg’s house. Also coming up are further performances of Pierrot Lunaire with Ensemble 360. She feels very fortunate to have the opportunities as if she is embarking on a one-woman campaign. And later this year, she is also doing the Second String Quartet.

As a young singer, Claire studied Pierrot Lunaire with soprano Jane Manning on a Britten Pears course. Manning had an incredibly accurate sense of pitch and a specific way of performing Pierrot Lunaire. The work was deliberately notated by Schoenberg to use Sprechstimme, he notates actual pitches but expects an element of recitation; it was written for the actress Albertine Zehme who had already developed a particular way of reciting. But, as Claire points out, whilst Schoenberg was particular in his notation for Pierrot Lunaire, over time the composer changed his views as to how Sprechstimme should actually be notated.

Claire is a firm believer in the necessity of being accurate when it comes to the pitches Schoenberg notated, and she points out that if you simply sing the vocal line, then the pitches sung prove to be important to what is going on musically underneath. Whatever else Claire does with the Sprechstimme, she wants it to be accurate and she comments that with the majority of other roles in the classical and 20th century repertoire, it is regarded as important that you are accurate but with Pierrot Lunaire, there has developed the idea that this does not matter. She goes on to emphasise that within the bounds of respect for the notes that are written, there is still lots of scope; once you find the notes, then there is lots that you can do with it. Schoenberg deserves that you be rigorous.

Yet the piece is so much more than a technical experience. Yes, you have to be accurate, but you should never lose sight of the need to listen to the players, you are part of that world and though you are part, there are times when you are not necessarily the most important voice. Since Jane Manning’s iconic recording of Pierrot Lunaire (she recorded it in 1991 but first recorded the work in 1967) there was not been another British recording and Claire is proud to be working on something passing that baton. It is a piece that Claire is known for, but each time she performs it, she reminds herself that you have to constantly make it new, yet remain within the parameters. If you start and end with what is actually written on the page, you won’t go far wrong.

|

| Vivaldi: Bajazet – Claire Booth, James Laing – Irish National Opera in 2022 (Photo Kip Carroll) |

Claire has put together what she calls a classical cabaret programme which includes music by Schoenberg (some of his Brettl-Lieder) alongside songs by Kurt Weill, Thomas Adès and John Woolrich. She has now commissioned Zoë Martlew to write something to add to this programme. Ever since Oliver Knussen died (in 2018) Claire has tried to think about ways to inhabit areas important to him, including commissioning composers in the manner that he did. Knussen admired the music of Zoe Martlew and Helen Grime, the two composers whose work Claire has commissioned for this year. Claire calls Zoë Martlew a terrific musician, adding that her vocal music is a triumph; she comes at vocal writing dramatically. Zoë Martlew’s piece for Claire, Hotel Babylon is being premiered this Summer at Petworth Festival and Fishguard Festival of Music with pianist Jâms Coleman, and they will be bringing the work to the Wigmore Hall in the Autumn.

Claire has wanted to work with Helen Grime for some time, having been really drawn to Grime’s orchestration so that a singer feels that their line is over the top of the orchestra, yet they are within it. Helen Grime’s new work, Folk, is based on Zoe Gilbert‘s book Folk, a set of short stories about people who live in a magical, mysterious version of the Orkneys. Claire calls the book very thrilling, and is delighted to be premiering Helen Grime’s Folk with Ryan Wigglesworth and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra in September. Ryan Wigglesworth is someone with whom Claire goes back a long way and she premiered his Augenlieder in 2009 (released on NMC Recordings in 2015).

In July, she will also be taking part in the premiere of Joe Cutler and Max Hoehn‘s Sonata for Broken Fingers – In the last days of Stalin’s reign, a mysterious phone call from the Kremlin launches a desperate search for a missing pianist. Inspired by the life of the pianist Maria Yudina (1899-1970), this new chamber opera explores the role of music in people’s lives during one of the darkest periods of Soviet history. Claire is playing Maria Yudina, though whether the anecdote used in the opera actually happened is less than clear. She is enjoying the sound world of Joe Cutler’s opera and says that it reminds her of the music of Jonathan Harvey. If (and when) the opera is staged, then her character needs to play the piano. Claire does actually play, and she comments that it would be a nice challenge to have to do this on stage in a contemporary opera, but the performance on 14 July is a concert one (and it is being recorded for Birmingham Record Company) so the fingers that you hear playing will not be Claire’s.

|

| Claire Booth (Photo: Sven Arnstein) |

- Claire Booth performing Pierrot Lunaire

- Corbridge Chamber Music Festival (27 July, St Andrew’s Church, 3.15 pm)

- Oxford International Song Festival (18 October, Levine Building, Oxford, 9.45 pm)

- with the Royal Northern Sinfonia (2 November, The Glasshouse, Gateshead).

- Further Schoenberg performances

- Lieder with pianist Christopher Glynn at Music@Malling (23 September, St Mary’s Church, West Malling, 7 pm)

- Quartet No. 2 at Music in the Round with Ensemble 360 (7 December, Crucible Playhouse, Sheffield, 7 pm).

- Claire and pianist Jâms Coleman premiere Zoë Martlew’s Hotel Babylon

- Petworth Festival (25 July, Champs Hill, Coldwaltham, 7.30 pm)

- Fishguard Festival of Music (29 July, Theatre Gwaun, 7.30 pm)

- London Premiere at Wigmore Hall (29 November, 7.30 pm).

- Claire joins Ryan Wigglesworth and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra to give the first performances of Helen Grime’s Folk

- 26 September, at City Halls, Glasgow

- 27 September at the Music Hall, Aberdeen

- Opera 21’s Sonata for Broken Fingers is a new opera by Joe Cutler with libretto by Max Hoehn

- Produced in partnership with Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, Birmingham Record Company and Royal Birmingham Conservatoire. Claire Booth leads the cast which also includes James Cleverton, Stephen Richardson, Lucy Schaufer and Christopher Lemmings under the baton of Sian Edwards (14 July, CBSO Centre, Birmingham, 4.30 pm)

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Something of a minor revelation: choral music by Giovanni Bononcini who was brought to England as Handel’s operatic rival – record review

- Pierrot Lunaire, Curlew River and a visit from the Hallé Orchestra: closing weekend of the 75th Aldeburgh Festival – concert review

- Youthfully engaging: a visually stylish new Rake’s Progress at the Grange Festival made us really care for about these characters – opera review

- A richly layered depiction of characters in all their fallibility: Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea at the Grange Festival – opera review

- The Sea and Ships: the London Song Festival celebrates the first Shipping Forecast to be broadcast on British radio – concert review

- Much more than a piece of history: Roderick Cox conducts Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 at the Royal Academy of Music – concert review

- Music like no other: Icelandic composer Gudmundur Steinn Gunnarsson’s Stífluhringurinn – record review

- New colours in old sound worlds: the Portuguese duo, Bruno Monteiro & João Paulo Santos in Elgar, Debussy, Ravel & more – record review

- Time remembered: the 75th edition of the Aldeburgh Festival lovingly recreates the opening night of 1948 Festival – concert review

- A disc that makes you think, but also satisfies as a recital in its own right: Songs for Peter Pears from Robin Tritschler & friends – record review

- Home

%20Britten%20Pears%20Arts%20(3)(1).jpg?w=998&resize=998,665&ssl=1)