|

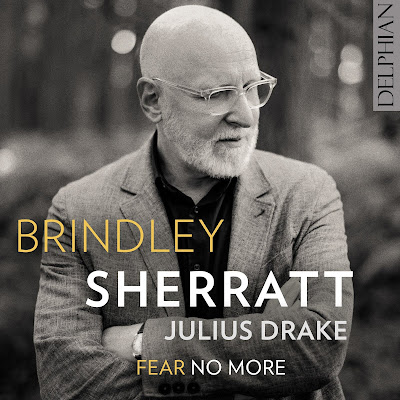

| Brindley Sherratt (Photo: Gerard Collett) |

I first chatted with bass Brindley Sherratt in early 2020 about a fundraising gala he was organising. Much happened afterwards, and the interview did not appear on the blog until 2022 [see my interview]. When we chatted then, Brindley was moving into singing larger, more dramatic roles including Wagner.

But when we met again recently it was to talk about a project on an entirely different scale, Brindley’s first recital disc, with pianist Julius Drake, Fear No More on the Delphian label. A disc that features music by Schubert, Richard Strauss, John Ireland, Gerald Finzi, Ivor Gurney, Michael Head, Peter Warlock and Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death.

Brindley suggests that, like most things in his career, his releasing of a debut disc is a bit topsy turvy as he is singing larger roles including Wagner and doing more recitals, both ends of the performing spectrum in other words. Some years ago, the mezzo-soprano Alice Coote told him that he needed to do some recitals and introduced Brindley to pianist Julius Drake.

Julius Drake suggested that Brindley come round and they would go through some repertoire. At the time, Brindley admits that he didn’t really know any songs. Lockdown intervened, but after a long time, they settled on a programme and performed it at the Oxford Lieder Festival and as part of Temple Song. Doing recitals had never been part of Brindley’s big plan, but once he started he found that he loved the process.

His first response, to having recital work suggested to him, was ‘No’. He was afraid of the intimacy of the recital hall. Normally, his audience is in the dark, some 80 feet away with an orchestra between. But he found that the very thing he had been afraid of was something he loved. He found he enjoyed the flexibility of a recital, just the two of them. And Julius Drake can play firmly and strongly, which means he lets Brindley be.

In recital, the singer does not have an operatic character to hide behind, but Brindley has no issue with that. He likes using the space that he is performing in; so, in a room where he can see the whites of the audience’s eyes, he uses that. He also uses the text, just as in opera, to communicate and weave himself into the text. When on the operatic stage he likes being honest and comments that he is not very good at what he calls operatic acting, for him, it all comes from the inside and so he likes the honesty of recitals. He also enjoys talking to the audience, and after his Wigmore Hall recital, people said that they loved the way he talked to them, telling funny stories about the songs.

For discs, singers often try to craft programmes that have an overarching theme, but Brindley found this difficult to do with the songs that he was singing. Also, it is relatively rare for basses to do recitals, and rare for a bass of his age and stage of his career to do a recording. The repertoire on the disc focuses on songs written for the bass voice, rather than using other repertoire which is transposed down.

|

| Brindley Sherratt & Julius Drake at the recording sessions for Fear No More (Photo courtesy of Delphian) |

All the Schubert songs on the disc, except for Tod und das Mädchen, were written for a bass voice in the bass clef, and even Tod und das Mädchen goes low. They reflect the bass voice’s character and are about subjects such as life and death. Similarly, Richard Strauss’s Im Spätboot was written for a bass, Paul Knüpfer, later a noted Baron Ochs in Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier. Knüpfer was also the dedicatee of Strauss’s two songs for basso profondo with orchestra. Though Mussorgsky’s songs were originally written for three different voice types (mezzo-soprano, tenor and bass), it is their association with singers such as Chaliapin that means we associate them with the bass voice. Brindley has sung them in the orchestral versions, but here he wanted to do them with piano. He describes the songs as macabre, cartoonish and on a large scale. When it came to including some English song, there were slim pickings, so he chose songs that he loved, songs that suited him, and transposed some down.

With the darkness and character of the bass voice, much of the music written for it is slow and often about death! This can be problematic when planning a recital, though some of the great German basses such as Kurt Moll and Gottlob Frick were regular performers of lieder recitals. Brindley always says to young basses that they must assume that, with this repertoire, their audience might get bored! There can be a lack of variety, so the singer needs to keep it vivid and sing on the edge of the voice as there are no lovely bright overtones to use.

Everything on the disc is sung in the original language, but he comments that something happens in the room when you sing in the language of the audience. You can create something special, something engrossing. The glory of much of the song repertoire is the text, yet singing in English gets you inside the songs quicker. And we talk about Jeremy Sams‘ new English versions of Schubert’s Winterreise and Schwanenegesang [I heard the latter performed by John Tomlinson and Christopher Glynn, see my review]. Both are works that are on Brindley’s bucket list. He worked on Winterreise during Lockdown and is now looking at it properly.

There has been a suggestion of doing a staged version of Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death (though there would be a question of what music to put with it). But this would be in English. The songs sound impressive in Russian, but the text is so cruel and over the top, Brindley feels the effect in English is quite electric.

In recital, he just uses operatic arias as encores, so an aria from Bellini’s La sonnambula makes a lovely light finish. But a lot of bass arias in opera are slow, so he often tends to go for Kurt Weill or Rogers & Hammerstein (the role of Emile in South Pacific was written for the great Italian bass, Ezio Pinza). At the Wigmore Hall, Brindley sang Weill’s September Song (written for the 1938 musical Knickerbocker Holiday, to be sung by actor Walter Huston whose voice is described as low and gruff). Brindley calls the song ‘fantastic stuff’.

In opera, performing is a lot about making sure that you are heard, so in recital Brindley finds it lovely to be able to ‘take his foot off the pedal’ and be intimate. He wants his voice to remain melodic, as well as being loud and dark, for as long as he can. He mentions the bass Gottlobb Frick, a notable Hagen in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung who came out of retirement at the age of 68 to sing Gurnemanz in Solti’s recording of Parsifal and demonstrated a beautifully preserved voice.

Brindley’s plans for this year originally included Hagen in Götterdämmerung with Vladimir Jurowski and thge London Philharmonic Orchestra, but unfortunately minor surgery and a significant recovery time have forced him to take time off, something he is considering in a positive light as a sabbatical. He comments, wryly, that he will probably take the time to learn Winterreise and to ride his bike. He has been flat-out since the end of Lockdown, so it is good to take time out and stay at home.

When we met up back in 2020, it was because Brindley was organising a gala at Glyndebourne in aid of The Meath, a residential care home for people with complex epilepsy where Brindley’s daughter, Amy lives. When the gala finally went ahead in 2022, they sold over 1000 tickets and he describes it as a joyous day. It also raised £300,000 for The Meath, which Brindley proudly points out secured music therapy for all residents for three years and paid for the roof of one of the buildings. A contribution that makes a big difference to what is quite a small charity. Now another roof needs replacing and Brindley has hopes for another gala.

Never miss out on future posts by following us

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- A German in Venice: Schütz alongside music he could have heard in Venice, a wonderfully life-affirming disc – record review

- Attention must be paid: the Engegård Quartet at Conway Hall in Mozart, Bartok, Maja Ratkje, and Fanny Mendelssohn – concert review

- Opera as it ought to be: Mozart’s Don Giovanni from Hurn Court Opera reviewed by James McConnachie – opera review

- Leeds Lieder 2024

- A Leeds Songbook and a showcase performance: Leeds Lieder Young Artists 2024 – concert review

- A day of French song with a focus on Fauré, with Graham Johnson making us love the composer’s late period, and James Gilchrist in fine form – concert review

- Engaging the audience: James Newby and Joseph Middleton in a folk-inspired programme at a cool Leeds café/bar – concert review

- The sound of an image: recent chamber music by New York City-based, Puerto Rican-born composer Gabriel Vicéns – record review

- A City Full of Stories: Anna Phillips on her work with Academy of St Martin in the Fields’ SoundWalk – guest posting

- Energy, discipline, & sheer love of music-making: National Youth Orchestra & National Youth Brass Band in Gavin Higgins – concert review

- No boundaries or rules: Yorkshire-based Paradox Orchestra is reinventing the orchestral concert – interview

- Full of good things: Sean Shibe and the Dunedin Consort in John Dowland, a new Cassandra Miller concerto and much else besides – concert review

- A little bit of magic: Victoria’s Tenebrae Responsories sung one to a part at the original pitch by I Fagiolini and Robert Hollingworth – record review

- Dramatic Britten, athletic Watkins and high-energy Mozart: Britten Sinfonia, Ben Goldscheider and Nicky Spence at Milton Court – concert review

- Home