As part of the BBC Symphony Orchestra‘s Total Immersion: Symphonic Electronics day at the Barbican on Sunday 23 February 2025, Ilan Volkov will be conducting the orchestra in the UK premiere of Steven Daverson‘s Figures outside a Dacha, with Snowfall, and an Abbey in the Background with Carl Faia on live electronics. A co-commission from the BBC and West German Broadcasting, Figures Outside a Dacha, with Snowfall, and an Abbey in the Background is inspired by director Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1983 film Nostalghia and bridges the gap between classical and electronic soundscapes to explore themes of memory, loss, and metaphysical power in a Tarkovsky film.

|

| Steven Daverson |

Steven became the youngest-ever recipient of the Composers’ Prize of the Ernst von Siemens Musikstiftung in 2011 and was awarded the RPS Composition Prize in the same year. He studied at the Royal Northern College of Music (RNCM), Manchester, with David Horne. He received his doctorate in composition from the Royal College of Music in London, studying under Jonathan Cole and additional postgraduate tuition from Mark-Anthony Turnage. Steven is currently Professor of Composition at the RNCM and Supervisory Tutor in Composition at the University of Cambridge.

On his website, Steven describes the inspiration for his intriguingly titled work, thus, “The final shot of Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Nostalghia (1983), shows a man and a dog sitting on the ground near a pool of water, staring down the lens, with a small Russian farmhouse in the background. The camera zooms out slowly over the course of almost two minutes, revealing that the entire scene is contained within a vast Italian abbey, only glimpsed initially through the reflection of the arched windows in the pool. The camera pauses, and snow begins to fall.”

Steven’s choice of title for the work was deliberate, he wanted something painterly, something that gave the impression of an image even if it was not cinematic, and that a more gnomic title would be too clinical.

It is written for orchestra and live electronics, which Steven admits is not unlike writing for two orchestras, and he adds wryly that perhaps he should have added an organ part which would mean writing for three orchestras. Whilst Steven was introduced to electronics whilst studying, he was taught in a way that rather put him off and for a long time he maintained that acoustic instruments could simulate everything electronic. His point of view has now changed, and he feels that there are certain types of grammar that electronics allow such as spatialisation or the speed of gestures. He mentions the Conlan Nancarrow studies which only achieved their effects using a player piano.

In his piece, the electronics create what he calls metaphysical auras (a name that has a nod to Harrison Birtwistle‘s use of the term in The Mask of Orpheus), these are soundscape-like, moulded in the moment, an environment being created by orchestra and electronics. But he is very keen to emphasise that the work is for orchestra and electronics, and he says that one of the most unsatisfying instrumental experiences is to be a bit part to a tape. He mentions composers saying they are using electronics to extend the capabilities of instruments, but who do so by having the instruments simply play long notes and drones. In contrast, as far as Steven is concerned, the orchestral part should be complex, as advanced a palate as that of the electronics. He intends the electronics and orchestra to be on an equal footing, something that was important to him from the outset.

He trained as an orchestral musician, he describes himself as a fallen bassoonist, he grew up in orchestras, where the sound in the room was being produced simply by humans. Whilst there is amazing electronic music being written simply using speakers, for Steven the performative aspects of a piece are important, and he sees these performative aspects as being the way of connecting the orchestra and the electronics. He emphasises that when he is combining the two, harmony does not disappear and instead, he creates a unified voice between the two.

|

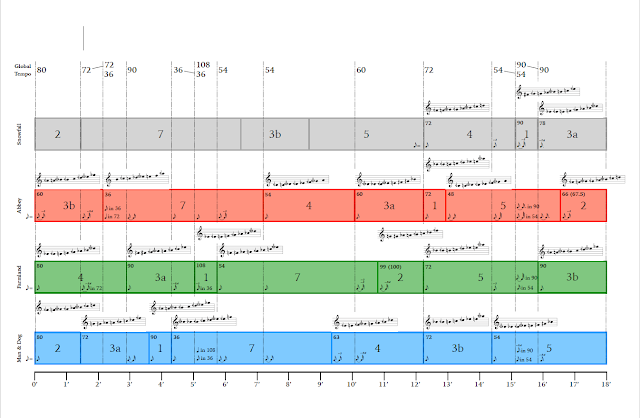

| Steven Davorsen’s conceptual sketch for Figures outside a Dacha, with Snowfall, and an Abbey in the Background |

Instrumentally, Steven has written the piece in a series of layers, and each of the four layers refers to an element in the film.

- The man and the dog: earthy, elemental and violent, often played primarily by an amplified ensemble in front of the orchestra

- The grassland: granular, constantly moving, with slow bowing and multiphonics, unstable like the wind across the grass

- The Abbey: bell-like material, spectral with chant-like movement almost quasi Arvo Pärt

- Snow: this comes in much later, and is partly instrumental along with flexible electronics, trilling, delicate wispy sounds, chilling cold flakes of snow.

The whole orchestra is spread across the different layers, with elements in each. Steven sees it as a very integrated sound-world, everybody has to do a bit of everything. He finds binary orchestration rather unsatisfying, where, say, all the flutes do just one thing. For Steven, the joy in writing for an orchestra is the sounding together, the blend.

|

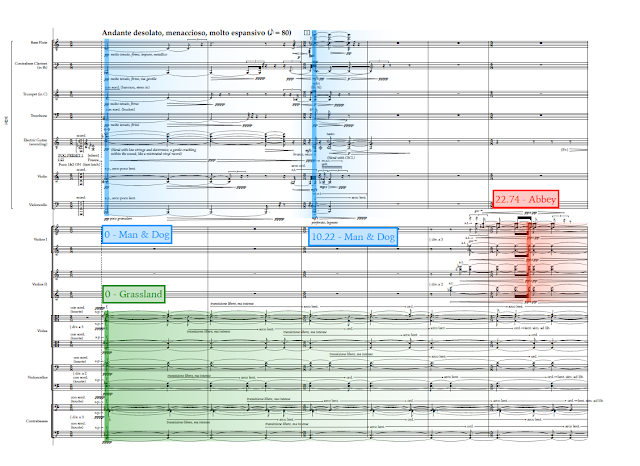

| Steven Davorsen’s Figures outside a Dacha, with Snowfall, and an Abbey in the Background |

His writing for the electronics is tightly notated and he likens it to Luigi Nono’s writing in the 1980s. Steven uses a clef along with pictograms along with an indication of how the signal should be put through the patch. When writing for electronics, Steven uses Max/MSP and has worked closely with Carl Faia, a colleague with whom Steven worked at Brunel University, who is responsible for the live electronics in the concert. Steven uses poetic descriptions of the sounds that he wants, to give Faia flexibility and freedom when creating the electronics. Steven gives me two examples:

Like a stiff breeze across a field. Noisy, benign, and smooth, but with a papery texture of delicate imperfections and artefacts.

Resting on the surface of the orchestral texture like a foam

And after the conversation, I have the completely mad idea that these texts would themselves make an interesting basis for setting text for another work entirely.

The electronics in the new piece include an element of sound design which was beyond Steven when he started work on the piece, hence his involvement of Carl Faia. Steven credits Faia with being instrumental in the work and whilst now, Steven has the capabilities to run/play the live electronics himself, the sheer time pressure of producing the work (two years to write and make the score, even before programming the patches for Max/MSP), made it impossible for him to do everything. His score also uses Italian terms, so the opening is marked Andante desolato, menaccioso, molto espansivo. Steven comments that he was forced to learn all the Italian terms as a teenager because he would need them for college! In fact, he didn’t need them, but he is determined to use them, and feels that musicians respond to them differently to English terms.

Whilst the work is inspired by Tarkovsky’s film, Steven emphasises that the listener does not need to know it. He feels that it is important that the listener does not need an extensive knowledge of anything outside of the piece, and a crucial point is not to do an analysis of the film. He is not expecting a particular response from his audience, ‘a response is a response’ and another crucial point for him is to allow space for the free play of the imagination, space for thinking. Steven mentions Birtwistle again, and his uncompromising statement about not worrying about the audience. Birtwistle has been seen as denigrating the audience, but Steven has a different take on it, feeling that it pays the audience a compliment, saying you are intelligent enough to respond yourselves and do not need a narrative thrust down your throat.

Steven’s older pieces of music do not use electronics, but now he has to make a conscious effort not to include electronics. He is now more likely to use electronics in a work; it is not a given, but it is part of his grammar. He is currently writing a piano piece for Nicolas Hodges and is making this about fingers on the keys only, not even any preparation in the piano. Also, he still rather likes the idea of a purely acoustic classical piece. But starting working with Max/MSP has changed the way he thinks musically.

His journey with electronics started properly in 2014 when he received a commission from Darmstadt which was a deliberate provocation, asking him to use electronics. The result was perhaps not his best work, but the process of creation had an impact on him and he now loves the process. However, he still works by hand, and he loves the procedure of making a patch (for Max/MSP), which feels very tactile. He has never worked with tape (or other fixed media), for him electronics is an instrument that is responsive, and that is led by a person who is in the room. Again we come back to the performative element that Steven mentioned earlier in our interview.

His piano work for Nicolas Hodges, Figures Outside a Dacha, with Sunrise, has been a long process and Steven describes writing piano music as hard. The new piece is related to another scene in Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia and is similarly layered. Writing something layered, contrapuntal and gesturally diverse to be played by just two hands is a tough process. Steven has been writing studies which work towards the main piece.

Also coming up, he is writing a work for saxophone and live electronics for Darmstadt. This will be premiered by Patrick Stadler. The piece will be modular and semi-improvised, which is a new departure for Steven. Some of it is in mensural notation, where the pitches are given but the phrasing is up to the performer, and the piece will change according to the date of the performance, and there is even an algorithm for creating the title based on the date. Steven is working with Patrick Stadler on the piece, so that it is technically different each time, yet remains learnable and not too onerous to tour. Currently, there are performances planned in Darmstadt, in Steven’s home town of Northampton (the first performance of his music there since 2003) with other festivals in discussion.

Figures outside a Dacha, with Snowfall, and an Abbey in the Background was premiered in Cologne in 2023. The work was written during the pandemic so the first performance was planned under German radio COVID restrictions [see WDR website]. The full version was for 70 orchestral players, but he was asked to reduce it down to 55. The challenge for Steven was to make the parts for the remaining 15 players interesting enough, yet it wouldn’t matter if they were not there. The BBC has opted to perform the full version, and Steven comments that maybe after the February performance he might say the piece has to be performed by 70 players.

Also in the concert is a new piece, Intrusions, by Misato Mochizuki, a Japanese composer based in Europe along with Tristan Murail‘s Gondwana, a work that Steven requested. The evening concert the same day features a new piece by Shiva Fesharecki and Stockhausen’s Cosmic Pulses. The result is a pair of concerts with interesting balances. The Stockhausen is symphonic electronics without an orchestra, whereas the Murail piece is for a large orchestra, spectral music with no electronics yet evoking it. .

In fact, planning for Steven’s new piece began way back in 2016 when they had the first meeting about it. Then, Steven imagined it being performed in a more traditional concert and in fact, he suggested a programme to include Sibelius’ Tapiola and Nielsen’s Symphony No. 5. With any new piece, Steven tends to give suggestions for the programming, and then rather wryly adds that perhaps he ought to start providing lists of pieces he would veto as companion works!

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Beyond Ravel: Mathias Halvorsen comprehensively demonstrates it is well worth exploring Paul Wittgenstein’s commissions – record review

- Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach is somewhat undeservedly squashed between his brothers, but this disc shows his music well worth exploring – record review

- ‘They are all gone now, and there isn’t anything more the sea can do to me’: Riders to the Sea – interview

- A glorious, yet sophisticated noise: Handel’s Solomon from Paul McCreesh & Gabrieli with Tim Mead – concert review

- A highly effective synthesis: James Joyce’s The Dead in a dramatised reading from Niamh Cusack with music from The Fourth Choir – review

- Creating a personal world: Ethel Smyth’s earliest orchestral work alongside new pieces by inti figgis-vizueta & Ying Wang – record review

- The complete Walton songs: there aren’t that many but Siân Dicker, Kyrstal Tunnicliffe, Saki Kato certainly make us understand why they are all worthy of attention – record review

- The idea of Greece: Robin Tritschler and Jonathan Ware in a wide-ranging recital from Schubert, Loewe & Wolf to Shostakovich, Dvorak, Berkeley & Ravel – concert review

- Uprising! Director Sinéad O’Neill on Glyndebourne’s new community opera written by Jonathan Dove and April De Angelis – feature

- Drawing us in: baritone James Atkinson makes his Wigmore Hall debut with pianist Iain Burnside in a programme moving from Robert to Clara Schumann to Brahms’ late tombeau for Clara – concert review

- Home

%20Steven%20Daverson%202024.JPG?w=998&resize=998,665&ssl=1)