|

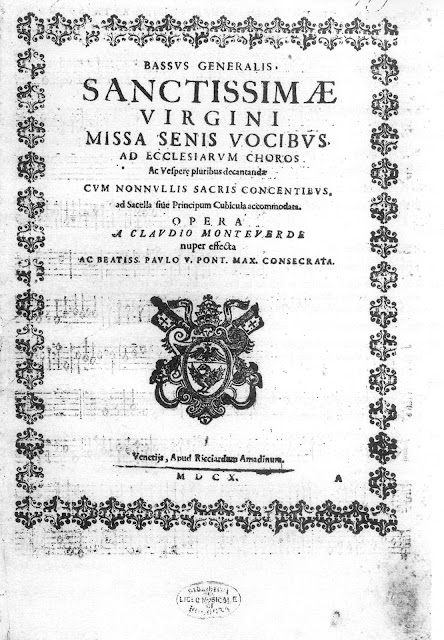

| Title page of the “Bassus Generalis” for one of the partbooks in which the Vespers were published in 1610 |

Monteverdi: Vespers of 1610; Solomon’s Knot; Wigmore Hall

Reviewed 12 October 2024

A chance to hear Monteverdi’s vespers in an acoustic bringing out the more intimate qualities, with the highly communicative singers enjoying the more madrigalian elements of the music

After hearing The Sixteen in Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 in the acoustic splendour of Temple Church [see my review] earlier in the week, on Saturday it was the turn of a rather different approach.

Solomon’s Knot, artistic director Jonathan Sells, returned to Wigmore Hall on Saturday 12 October 2024 with their own distinctive take on Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610, performed by ten singers and 14 instrumentalists, all on a very full Wigmore Hall stage.

The singers sang from memory, and stood in a circle with the instrumentalists behind. The result was quite a feat, both the sense of the singers performing directly do us without intervening music or music stands, but also giving such a complex piece without conductor and there were some passages that seemed to hover on the edge of the possible. It also brought out that, for all the grandness of the writing in some places, much of the work has an intimate quality.

In the Magnificat, singers only stood up when performing so that many movements were performed by just three or four, so that solo blended into duet or trio into ensemble. There was also a chamber feel to everyone’s approach, the sound was very much vocal ensemble, a group of individuals responding to each other (and we could clearly see them doing just that), with individual voices clear rather than a perfect blend. There was also a feeling of spontaneity to it, with each shaping lines accordingly.

This approach is probably closer to what Monteverdi might have imagined. What I missed, however, was a bit of space in the acoustic. In the clarity of the Wigmore Hall, everything came over admirably yet the slightly dry warmth did not compensate for the air that a more generous, church acoustic might bring. That said, it was glorious being able to hear the detail in such clarity.

The opening Deus in adiutorium was strong, almost a wall of vocal sound with the instruments providing coloration. By contrast, Dixit Dominus was fleet and almost madrigalian, linking to Monteverdi’s larger-scale madrigals (by the time he came to write the work he had already published five volumes of madrigals). Laudate Pueri was sung by just eight singers (we lost two tenors), it was full of contrasts between line and rhythm, with a lovely attention to detail and real bounce in the joyful Gloria patri. Laetatus sum, which began with a wonderful bassoon line from Inga Maria Klaucke, was fleet and full of detail, the music ebbing and flowing. Nisi Dominus featured perky off rhythms with a great sense of dialogue between the choirs. Lauda Jerusalem was bright, with lively rhythm and colour. Sonata sopra ‘Sancta Maria’, taken at a stately pace, was full of colour and movement, giving the instruments a chance to show off with no singers on stage (the two sopranos were at the back of the hall, gradually moving forward.) Ave maris stella, sung by eight singers, was an intimate madrigal, it flowed yet was not rushed, there was a sense of immense care. And for the solo verses, the other singers sat down, giving more of a sense of the way the music flowed between ensemble and solo.

David de Winter was intimate and not a little seductive in Nigra Sum, singing with bright focused tone, yet giving the sense of confiding and often fining the voice right down. This was the type of performance that would not really be possible in a large acoustic. Zoe Brookshaw and Emma Walshe made Pulchra es into something remarkably intimate, bringing out the madrigalian undertones in the way they sang the duet as a love song to each other. Duo Seraphim featured Thomas Herford and Gwilym Bowen duetting, later joined by Thomas Kelly. Taken at a leisurely pass, Herford and Bowen relished the long lines and the end developed into some wonderful competitive ornamenting from the three.

Audi Coelum featured Gwilym Bowen giving us a vividly strong line and great sense of rhetoric, complemented by Thomas Herford’s evocative off stage echo, and when they were joined by the choir it felt as if the rest of the ensemble were just joining in rather than being blasted by the full force of a choir.

The sense of a blend of ensemble and solo came over strongly in the Magnificat, here few moments were mammoth tuttis. The work was performed at the historically correct low pitch, so we lacked the edge of the seat moments and instead had music that sat in the middle of singers and instruments tessitura (by and large, for some of the plainchant the two altos were joined by tenor Thomas Herford). David de Winter and Thomas Kelly were exuberant in Et exultavit, whilst the other two tenors were laid back and calm in the following verse yet surrounded by instrumental colour and movement. There was a dark exuberance to the bass duet, Quia fecit mihi magn, whilst Et misericordia, sung by the lower voices, a deep, dark intimacy to it. Deposuit featured wonderfully mellow cornets, and they were fabulous in Esurientes implevit too. There were plenty of perky moments with vocal and instrumental lines weaving their way around that chant. For the Gloria patri David de Winder was vividly ecstatic giving it an improvisatory feel with fine echo from Gwilym Bowen. The ending, with everyone, was full of colour.

This was a chance to hear Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 in a rather different way, the acoustic bringing out the more intimate qualities, with the highly communicative singers enjoying the more madrigalian element to the music.

- Emma Walshe soprano, Zoë Brookshaw soprano, Kate Symonds-Joy alto, James Hall alto, Thomas Herford tenor, David de Winter tenor, Gwilym Bowen tenor, Thomas Kelly tenor, Jonathan Sells artistic director, bass, Alex Ashworth bass

- Magdalena Loth-Hill violin, leader, George Clifford violin, Joanne Miller viola, Nichola Blakey viola, Gavin Kibble bass violin, Jan Zahourek violine, Toby Carr chitarrone, Inga Maria Klaucke bassoon, Gawain Glenton cornet, Conor Hastings cornet, Emily White sackbut, Peter Thornton sackbut, Adam Crighton sackbut, William Whitehead orgam

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Waiting till they feel they have something to say: I chat to Trio Bohémo about their debut disc – interview

- On tour from New York, the Philip Glass Ensemble stopped off in Cambridge in a presentation by the Cambridge Music Festival – concert review

- Everyone clearly enjoyed themselves & brought the house down: The Sixteen in Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 at Temple Church – concert review

- Une messe imaginaire: Bruckner & Frank Martin from Lyon – record review

- What lies beneath: a brilliant reinvention of Judith Weir’s Blond Eckbert at the heart of ETO’s exploration of German Romanticism – opera review

- A glorious noise: from one to eight choirs in I Fagiolini’s evening of music from 17th-century Venice and Rome – concert review

- After the humans are gone, the instruments still sing and it is important to listen – Jake Heggie on his song cycle, Intonations: Songs from the Violins of Hope – interview

- Innate theatricality: composer Adrian Sutton definitively moves out of the theatre with a challenging yet engaging concerto for violinist Fenella Humphreys – record review

- Eternity In An Hour: Keval Shah and Jess Dandy on their unique reimagining of the Bhagavad Gita – feature

- A focus on the flute: London Handel Players in a group of cantatas Bach wrote in 1724 with virtuoso flute parts – concert review

- Home