And then there’s this – whatever it is John Wilson is doing with his Sinfonia of London strings and that manic vibrato. Oh it’s definitely recognizable in a way Makela’s is not (but not necessarily in a good way) and it’s cropping up on his every new recording (definitely not in a good way). What I don’t understand is why his string section goes along with it and willingly does it for him. I would think the “leader” of this orchestra would put his foot down and put a stop to it. (Does he listen to these recordings? Doesn’t he hear how ridiculous that sounds?) But I have a theory on that (discussed below), and in the end, there can be no doubt this ultimately is all John Wilson’s doing.

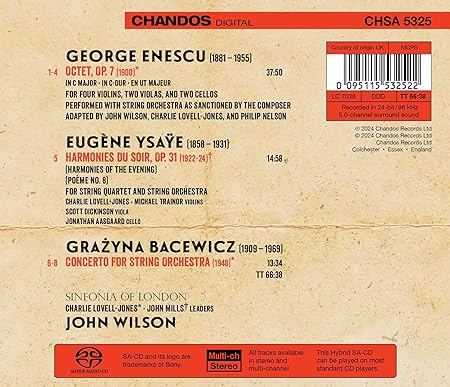

I admit I was almost dreading this release after what I heard in this team’s previous recording of the Berkeley Divertimento. (Please see my review here on the blog for details about it.) This program is so adventurous and enticing, I really wanted to like it. But I wasn’t looking forward to hearing what Wilson and his merry band were going to do to it. So I thought I’d start with Bacewicz’s terrific Concerto for String Orchestra (which is becoming quite popular lately), as I was sure it would keep the violins busy enough to not start in with that wild vibrato. I hesitantly pushed track 6 on the remote and sat back hoping it wouldn’t come.

And it didn’t take long.

Just 3:15 into the opening Allegro, as the melodic violin line begins to soar with increased intensity, they let loose with it. And boy-oh-boy do they ever. It’s that frenzied vibrato I heard in their earlier Berkeley. And now it can even be heard down in the violas (and maybe even the cellos?) too. UGH. Fortunately, it makes only a brief appearance before they all settle down and become a little less excitable and proceed with making music again.

And make music they do in the Andante (which can be ravishing in the right hands). And, well, it is positively ravishing here. That mega-fast vibrato Wilson likes, when applied in moderation and with good taste, can be exquisitely shimmering. And here in the Andante, played con sordino, the string sound is truly lush. And a little later, Wilson takes his time in the calm, desolate interlude, allowing vibrant, singing viola and violin solos to emerge from the starkness of the atmosphere. Wilson is superb at this, and this was a truly memorable moment.

The final Vivo then takes off with vigor, just as it should, and Wilson drives it pretty hard – barely letting up even for the Meno sections along the way. And mercifully, his violins are well-behaved.

Comparing Wilson to Paavo Jarvi in his recent recording of the piece for Alpha Classics, I was surprised to hear more similarities than differences. And I suppose that is a testament to the accomplishment of Bacewicz’s writing and scoring. Sonically, Jarvi’s strings are just a bit thicker and bass-heavy, while Wilson’s are more textured and bathed in an almost too-warm acoustic.

Musically, there are minor differences worth noting. For instance, Jarvi brings out the melodic lines more, giving them space to sing, while Wilson likes to bring everything out, whether important or not, creating a busyness underlying it all. Jarvi’s strings are not quite as luscious in the Andante, but he relaxes beautifully in the Meno sections of the finale, slowing noticeably more than Wilson does, creating more variety and illuminating wonderful contrasts. Both men bring enormous gusto to the conclusion – Jarvi’s bowing a little more incisive, and Wilson’s just a bit heavier on the string. Wilson tends to sound a touch more driven, as is his usual style.

In the end, it would be difficult to choose between the two. Both are outstanding and receive excellent recorded sound.

Since I started with the last piece on the disc, I decided to work my way backwards and listen to the Ysaye Harmonies of the Evening next. It is scored for string quartet and string orchestra, which I feared might get a bit thick with all the dense string sound rebounding around that enormous church they record in. (And occasionally it does). But even more, I was hoping with fingers crossed Wilson wouldn’t ask them for that ridiculous vibrato. Can we just get through one piece without it?

The answer is – not really. Nevertheless, I ended up enjoying this piece very much (even though it is quite long). It conjures the soundworld of Scriabin and I was instantly drawn into its awesome, alluring aural landscape. The quartet of strings is placed in front, but not unnaturally so, with the tutti strings sometimes a bit indistinct and wooly back behind them. But it isn’t too serious, and later, they sound gorgeous in con sordino passages.

As I was relishing the expressive solo violin playing of concertmaster Charlie Lovell-Jones, I quickly noticed his vibrato can get awfully fast and nervous at times, which makes me now wonder how much of what I hear from the full section is actually coming from him – perhaps emphasized by a too-close microphone. Or more likely, encouraged too much to go too far by the conductor. But he just keeps it in check here in his soloistic passages, producing a shimmering silkiness which is lovely to listen to.

As it went on, I noted impressive dynamics (especially on the loud end – typical of John Wilson), but also a bit of congestion in the bigger, most intense tutti passages, swamped in the reverberation. Elsewhere, though, textures lightened beautifully – the enormous hall enveloping the sound with a cushion of air over bowed textures and golden richness, with some positively sumptuous string sound.

Taking a break after this, I came back on a different day to listen to Enescu’s substantial, very long (almost 40 minutes!), very Richard Straussian Octet, in this version (approved by the composer, though with instructions) for full string orchestra. And I was quite simply blown away. What an incredible, moving piece of music. And Wilson is quite simply magnificent in it. However…

(and you know what’s coming)

It begins with drama – passionate soaring lines, vibrant solo violin and viola in animated conversations, and rich rhapsodic tutti passages. Wilson excels in this kind of music, bringing out the endless variety of moods, emotions and energy levels without becoming too melodramatic. This opening movement is very long (nearly 13 minutes), but it doesn’t feel that way. Wilson keeps it moving – both propulsively and emotionally – finding light and shade textures as he increases and then eases the drama. And he gives the solo cello plenty of time for a heartfelt moment of reflection in the central section, which is very moving indeed.

And this string section once again demonstrates it is one of the very best – enormously impressive in its responsiveness, quickfire dynamic swings, and amazing variety of vibrato speeds. And about that vibrato, it gets very, very fast in places, adding overwhelming tension. And the violins become practically hysterical at times – screaming (almost screeching) at the heights of ecstatic intensity. I’ve never heard anything quite like it.

And they’re not done yet.

The Second movement is vigorous and Wilson elicits some impressive, incisive bowing from his players. But it’s not quite hard-driven (which is good). He brings some delicacy and lightness here and there, at least until the final section, where he just can’t help himself and drives it home hard.

However, (and here it comes), as this movement progressed, I became increasingly concerned as these violins grew more and more agitated, getting overexcited and frenzied, and their vibrato gets faster and faster and eventually absolutely frantic. (And once again I’m hearing it predominantly from the 1st desk of violins. Why are they doing that? And why is the engineer highlighting it?) Ultimately it becomes ridiculous. However, I wasn’t as bothered by it here because Wilson is whipping up such a frenzy from the entire ensemble, the violins are really working hard to remain the center of attention. Musically I can just barely accept it in this context, but I do wish they wouldn’t go berserk with it.

Moving on to the Lent – it is, in a word, lovely. Too long, yes, but Wilson keeps it moving and does his very best to make it sing – at times with a delicate sweetness, and others with passion but not heaviness. I was surprised to discover this piece was composed some 45 years before Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen – it sounds so much like it I would have expected that Enescu had been strongly influenced by it. But it’s the other way around!

The Lent crescendos into the finale without pause, establishing a vigorously rhythmic Valse, consistently ebbing and flowing in intensity and mood. Wilson’s way with it is splendid – and the vibrato is kept in control until about the 6-minute mark, where the easily excitable violins simply can’t contain themselves any longer and the hysterical screaming heard in the 1st movement makes an unwelcome return. The piece ends with ferocity and frantic intensity, leaving one rather exhausted and emotionally drained.

Despite its length, this is undeniably a fantastic piece, brought vividly (and vigorously) to life by Wilson and his incredible orchestra. The Chandos recorded sound is excellent too – a bit more forward (but not too much) and better focused than in the rest of the program, to great advantage. (The booklet reveals it was recorded at a later session than the rest.)

I do think Enescu’s Octet should have come last on the program, and perhaps beginning with Bacewicz’s energetic concerto, which would have been a splendid concert opener. But that’s a minor quibble. In the end, this a fantastic program of music. And other than my constant irritation with the vibrato, this really is a sensational album.