|

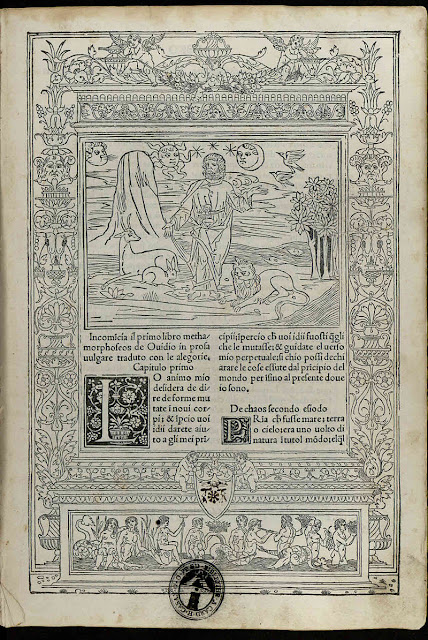

| Page from the edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses published by Lucantonio Giunti in Venice, 1497 |

Marc-Antoine Charpentier: Actéon, Jean-Philippe Rameau:Pygmalion; Anna Dennis, Rachel Redmond, Katie Bray, Thomas Walker , Academy of Ancient Music, Laurence Cummings; Barbican

Reviewed by Tony Cooper, 9 October 2024

Rarities on the British stage such dramas of human emotion and divine power contained in Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Actéon and Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Pygmalion were penned by two of the most imaginative and well-respected composers of the French baroque era.

The Academy of Ancient Music’s two mythological masterpieces of baroque opera, Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Actéon, and Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Pygmalion, sung in French at London’s Milton Court Concert Hall was blessed by an extremely fine and stellar quartet of soloists comprising Anna Dennis and Rachel Redmond (sopranos), Katie Bray (mezzo-soprano), Thomas Walker (tenor) and Laurence Cummings (director/harpsichord).

Based upon the third book of Metamorphoses, written by the celebrated Roman poet Ovid between 1683 and 1685, the original title of Charpentier’s one-act opera is Actéon – Pastorale en musique; it received a private performance at the Hôtel de Guise, the house of the composer’s appreciative and wealthy patron, the Duchesse de Guise affectionately known as Mlle de Guise. The author of the libretto, however, is not known but is often thought as being Thomas Corneille. An associate of Jean-Baptiste Lully his adaptations of stories from the Metamorphoses bear a likeness to the libretto of Actéon.

The opening scene of Actéon witnesses the ‘hero of the opera’ leading a hunting party searching for a bear that’s ravaging the forests of the goddess Diana while the second scene depicts Diana and her attendant nymphs Arethusa, Daphné and Hyale enjoying naked bathing in a forest spring while in the third scene Actéon is seen spying upon them.

When Diana spots Actéon she duly punishes him for his voyeurism. He then realises from his reflection in the fountain in the fourth scene that he’s gradually turning into a stag. Little by little he loses all his human characteristics including his voice.

The hunting party’s dogs run wild in the fifth scene tearing the stag to pieces and in the last scene the goddess Juno announces to the hunters that Actéon has been devoured by his own dogs in the aria ‘His misfortune is my doing’ with the Chorus of Hunters jumping in lamenting his fate in their big number ‘Alas, is it possible’ thus bringing to a an end a delightful, interesting and thought-provoking work.

In Rameau’s one-act opera, Pygmalion, set to a libretto by Sylvain Ballot de Sauvot, who stripped away the raunchier aspects of Ovid’s famous tale, the opera is widely considered to be one of the composer’s best short pieces and first performed at the Académie Royale de Musique, Paris, on 27 August 1748. Incidentally, Rameau is supposed to have written Pygmalion (which he referred to as an ‘acte de ballet’) in a period of just eight days. Fast worker!

The simple, entertaining and whimsical story surrounds the sculptor Pygmalion who creates a beautiful statue and falls in love with his own creation much to the horror and despair of his sweetheart, Céphise, who demands his strict attention. As he spurns her, he then entreats the goddess Venus to bring The Statue to life. Magically, she does the trick on the spot while Cupid praises him for his artistry. In no time at all a knees-up gets underway with celebratory dancing and singing attesting to the mystical powers of Love while Cupid gets down to business finding another suitor for Céphise.

All in all the Academy of Ancient Music delivered an excellent evening of baroque opera played out in the comfort and warmth of Milton Hall, harbouring good acoustics and sightlines, performed by a glorious quartet of soloists comprising soprano Anna Dennis as Diana/The Statue, soprano Rachel Redmond (Arethusa/Cupid), mezzo-soprano Katie Bray (Juno/Céphise), tenor Thomas Walker (Actéon/Pygmalion) while members of the solo voice quartet – soprano Ana Beard Fernandez, mezzo-soprano Ciara Hendrick, tenor Rory Carver and baritone Jon Stainsby – excelled in their performance acting as The Chorus and so forth.

And the members of the Academy of Ancient Music, a truly fine bunch of musicians, thoroughly excelled in their performance, too, especially in the dance sequences (French opera since its inception has embraced dance) which kicks off with a few brief dance-like melodies giving way to a gentle gavotte, a menuet, then a faster gavotte while paving the way for a chaconne, loure, passepied, rigaudon, sarabande and tambourin as The Statue (dramatically portrayed by Anna Dennis) is taught how to move. The Chorus then majestically sings ‘Love is triumphant; proclaim his victory!’

However, Laurence Cummings (baroque master par excellence and AAM’s current music director) took the audience by complete surprise by turning from his keyboard and with score in hand, standing centre stage, vigorously sang the part of Pygmalion’s final air ‘Reign, Love, let your flames shine bright’ with the opera ending with the graceful dance melody: ‘Contredanse en rondeau’.

At curtain-call, Maestro Cummings was given ‘rock-star’ treatment by a wild, roaring and excited audience over his cameo vocal performance while gracefully embracing Thomas Walker to the delight of a full and admiring audience. Bravo!

And one last thought: Alistair Baumann’s splendid surtitles projected on to the gallery wall in an extremely large clear serif typeface were very informative. For instance, they not only depicted the English text but also stated the respective dance styles and so forth.

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Intimate & communicative: Solomon’s Knot brings its distinctive approach to Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 at Wigmore Hall – concert review

- Waiting till they feel they have something to say: I chat to Trio Bohémo about their debut disc – interview

- On tour from New York, the Philip Glass Ensemble stopped off in Cambridge in a presentation by the Cambridge Music Festival – concert review

- Everyone clearly enjoyed themselves & brought the house down: The Sixteen in Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610 at Temple Church – concert review

- Une messe imaginaire: Bruckner & Frank Martin from Lyon – record review

- What lies beneath: a brilliant reinvention of Judith Weir’s Blond Eckbert at the heart of ETO’s exploration of German Romanticism – opera review

- A glorious noise: from one to eight choirs in I Fagiolini’s evening of music from 17th-century Venice and Rome – concert review

- After the humans are gone, the instruments still sing and it is important to listen – Jake Heggie on his song cycle, Intonations: Songs from the Violins of Hope – interview

- Innate theatricality: composer Adrian Sutton definitively moves out of the theatre with a challenging yet engaging concerto for violinist Fenella Humphreys – record review

- Eternity In An Hour: Keval Shah and Jess Dandy on their unique reimagining of the Bhagavad Gita – feature

- Home