First performed on January 20, 1699, André Campra’s comic opera/ballet Le Carnaval de Venise to a libretto by Jean-François Regnard finally arrives at its UK premiere in late Summer 2025 at the Vache Baroque Summer Festival. It is sung in French, Italian and English, a heady mix and a real test (successfully passed) for the singers.

All this happened against the backdrop of the Chiltern Hills, a short journey fom Chalfont & Latimer station. La Vache Baroque started five yeas ago, founded by by Betty Makharinsky and the Music director for these performances, Jonathan Darbourne. This is a properly celebratory extravaganza: director James Hurley has referred to the opera as a “genre-bending blend of comedy and tragedy”. The action takes place over the course of one day of Venice’s famous carnival; the opera also includes a play-within-a-play (Orpheus in the Underworld; an idea not a million miles from Shakespeare’s Mechanicals in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, just with layers and layers of camp ladled on). We can make other parallels (and pre-echoes), too. The Prologue is set backstage, with a stage manager nagging away because the staging of Orpheus is so behind. Ariadne auf Naxos with a French Baroque accent (sung, though. in English) seems to be an unavoidable link; but here, Minerva arrives into the world of Muggles, shocked by the chaos. She calls on the Muses of Music, Dance, Painting and Architecture to help. Inevitably, as the opera proceeds, love entanglements come forward. And how.

The heart of the Italian commedia dell’arte is here in James Hurley’s production, as are Venetian masks and of course, gondola. The “inserted opera” is sung in Italian; French predominates elsewhere, apart from that English Prologue. Quite right, then, that this should be set in a (circus) tent, almost in the round (audience on three sides, band on the fourth). It is pretty immersive, although the audience are told to be as still as possible because of the acrobatics. Before the production started, two violinists (Naomi Burrell and Charlotte Faibairn) started playing duets in the grounds; warm-ups? Kind of, but warm-ups for the event, not themselves – the same players became part of the performance onstage, and the music director, Jonathan Darbourne, conducted the opera’s close from the stage, held aloft by the singers.

After the havoc of the Prologue, the first act is set in the Piazza di San Marco, Venice. Léonore (yes, another one) has lost the interest of her lover, Léandre, who has been juggling both Léonore and Isabelle. Confronting him, the two girls force him to make a choice; Isabelle is the chosen one. A commedia dell’arte troupe sings songs about love and Venice. In the second act, we have another complication:Rodolphe (a Venetian nobleman) also loves Isabelle. Together with Léonore, the two plot revenge against Léandre. There follows a brilliant scene of mistaken identities and admissions of love, but to the wong person.

With the third act, everyone believes Léandre is dead (of course he’s not). Mourning and near-suicide clarify Isabelle’s feelings, so that when Léandre eppears, nicely alive after a botched assassination attempt, Isabelle is crysal clear of her feelings. They can leave while the entire city of Venice is distracted by the opera’s final part, a setting of Orfeo in an Italian Underworld.

With such a plot and placement, contortionist acts and contortionist archery seem perfect: Hannah Finn lists herself as a “circus performer and high level contortionist” and she’s not kidding. Such is the pull of the production, though, that her remarkable what I can only call “bendiness” seems a natural part of the show; Associate Director Rebecca Solomon worked wonders with the circus magic component of the show.

So in amongst all the unbelievable events is love. There is chaos galore: Mineva is brilliantly taken by Katie Bray (who also sings Léonore), who rips up a play’s script just as the curtain id going up. The Prologue contains the essence of the opera, including dance (a nice spightly Passepied from the scaled-down band). Campra’s music shifts emphasis immediately for Act One and Léonore’s plaint of regret (“J’ai fait l’aveu de l’ardeur qui m’enflame”). This music and mezzo Katie Bray’s voice are made for each other,

Julieth Lozano takes the role of Isabelle, her act three lament, “Mes yeux, fermez-vous à jamais” beautifully touching. I was very taken by bass-baritone Tristan Hambleton’s song Rodolphe (the Venetian nobleman in love with Isabelle who plays such a par in the second act), while Giusppe Penningra was a superbly authoritative dramaically (as a as the campness allowed) Plutone, if not quite so confident vocally. Themba Mvula sang Léandre. This is a central character, but his dramatic presence seemed lower voltage than those around him; vocally, too, he was a touch less secure. Feargal Mostyn-Williams was an excellent Orfeo, Eleano Bromfield a fine La Fortune.

The lighting (Ben Pickersgill) is superb, perfectly calibrated to a work that shift emphasis and tone on a sixpence, ever supporting the prevailing mood, from the distraught to the extravagant. Director James Hurley and designer Laua Jane Stanfield have created miracles with the space and budget at his disposal, given Campra’s quixotic changes of scene and mood.

A fabulously inventive staging, well sung and supported by a group of ten players of extraordinary stamina.

Le Carnaval de Venise

Composer: André Campra

Libretto: Jean-François Regnard

Cast and production staff:

Léonore – Katie Bray; Isabelle – Julieth Lozano; Rodolphe – Tristan Hambledon; Léandre – Themba Mvula; Plutone – Giuseppe Pellingra; La Fortune, Soprano Chorus – Eleanor Broomfield; Orfeo, Alto Chorus – Feargal Mostyn-Williams; Le Chef des Castellans, Tenor Chorus – William Searle; Un Musicien, Bass Chorus – Adam Jarman; Circus Artists – Hannah Finn, Shane Hampden

Director – James Hurley; Associate Director – Rebecca Solomon; Designer – Laura Jane Stanfield; Lighting Designer – Ben Pickersgill; Sound – Dom Harter, Simon Honeywill (for Martin Audio).

Music Director/Harpsichord – Jonathan Darbourne; Musicians of Vache Baroque

The Vache, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, 31 August 2025

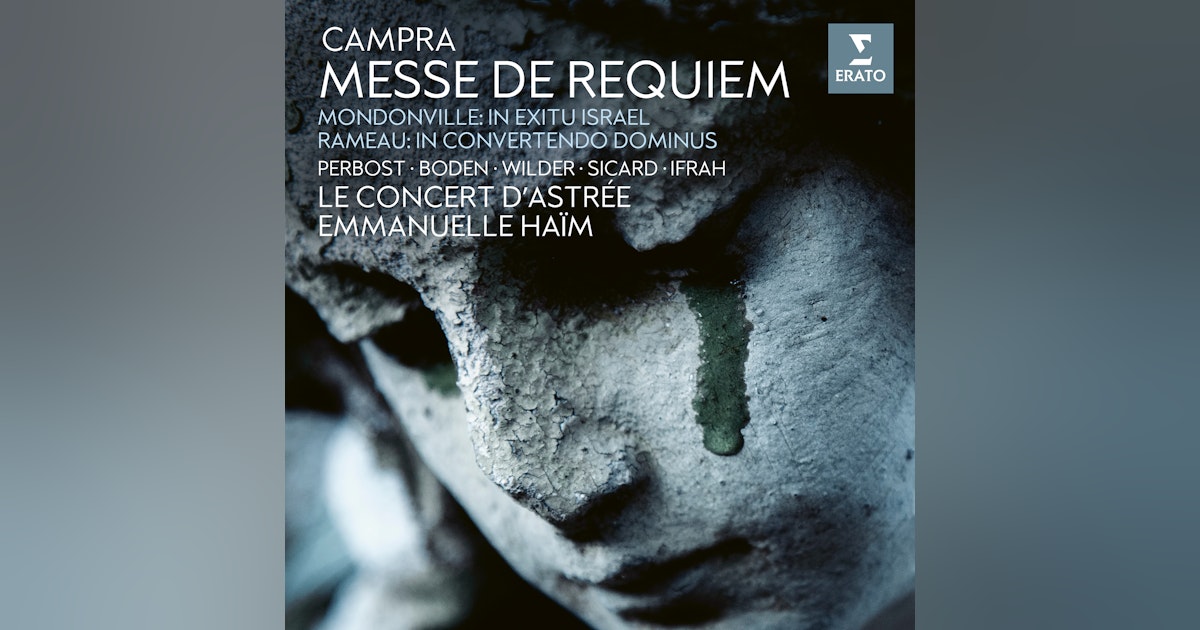

Born in Aix-en-Provence, France, André Campra was passionate about opera, but is probably best known today for his extraordinary Requiem (which itself has its more operatic moments): Emmanuelle Haïm and Le Concert d’Astéee on Erato provide a modern-day performance of extraordinary power (coupling it with Mondonville’s In Exitu Israel and Rameau’s In Convetendo Dominus). In the religious field, Campra rose to the heights of Maître de Musique at Notre Dame. But he also created what is generally known as the first opéra-ballet L’Europe galante (1697), each act of which is set in a different country; Venise is a further example of this genre.

That Mondonville is extraordinary, incidentally, and it is another pointer to the genius of this composer: remember this post on Mondonville’s miraculous opera Titon et l’Aurore? You can also read my review of a performance at Versailles on the Gramophone website. Mondonville’s In Exitu Israel (Psalm 114) contains the most remarkable movement that presages Philip Glass (you read that right), “Mare vidit”. Just have a listen:

. … and when it comes to the Rameau, In convertendo Dominus, this is like a virtuoso demonstration of the power of the descending line, Affektenlehre writ large, or perhaps the cover image of the crying statue in sound. Listen to this the final movement, “Euntes ibant et flebant”:

You can hear those descending lines right from the off, in “In convertendo Dominus,’ the first movement for haut-contre (high tenor, Samuel Boden). Here, it is Rameau’s extraodinarily expressive counterpoint in the opening (pre-voice) that is so impressive:

The Erato/Haïm recording is available at the magnificent price of £9.99 (it’s two extraordinary discs) here. Streaming below.

In another example of extreme generosity, Amazon is offering a whole 3% off Hervé Niquet’s superb recording of Le carnaval de Venise here.