The Easter edition of our Alastair Macaulay Review:

Charpentier and Louis XIV; Bach and Frederick the Great

by Alastair Macaulay

The overlaps between history and music are infinite, even though many of us listen (or think we are listening) to music as a history-free zone. Actually, for those of us who love to read history, it can be very salutary to listen to the music known to the people of whom we are reading. Louis XIV, the Sun King, tends to seem a singularly secular figure in most biographies; but we have only to listen to theatrical music by his beloved Lully to sense his secular side differently. Then, however, when we listen to the religious music of his day, and when we remember how important religious worship was to him, he changes again.

The American-French musician William Christie celebrated his eightieth birthday in December. Over more than forty-five years, his musical ensemble Les Arts Florissants has done much to transform our notion of the baroque in music, especially the French music of Louis XIV’s day, not least the operas of Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687) and Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704). (“Les Arts Florissants” is the name of a 1685 opera by Charpentier.) But it has also attended to the liturgical music of these composers.

On Wednesday 16, the Wigmore Hall with a selection of Charpentier’s “Leçons de ténèbres”, the vespers-type cantata settings of various Lamentations of Jeremiah. The later “Leçons de ténèbres” of Couperin are better known, but the fascination of Charpentier’s – sparse in instrumentation – is that they often feel experimental, as if the composer is trying out which words prompt which colours, trying out harmonies and combinations that will deepen the expressive effect of each sentence.

For this concert, the Wigmore Hall became tenebrous indeed, with lighting so low that, although pages of tenebrae words were provided in Latin and English, it was exceptionally hard to read any of them. (“So this is the Stygian gloom one has heard so much about,” says A.E.Housman in Tom Stoppard’s “The Invention of Love”.) The soloists were the Lithuanian tenor Ilja Aksionov and the Irish bass-baritone Padraic Rowan, both with fine senses of line, neither with sufficiently pointed diction to make the words carry. Aksionov is masterful in the various shadings (falsetto, voix mixte) that he brings to the upper tenor notes, an especially vital aspect of French vocal style.

Jump a few decades ahead and from France to Germany. Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), unlike his contemporary Handel, was largely removed from the high-level politics of his day. He was a father of several other prestigious composers: which was the subject of Nina Raine’s “Bach & Sons”, a play that opened at the Bridge Theatre in 2021, with Simon Russell Beale as the composer. But Bach, much of whose life was preoccupied by work and family, had one historic exchange with the man whose politics dominated the Germany of his day – Frederick the Great (1712-1786). Bach and Frederick (a renowned amateur flautist) shared music but little else.

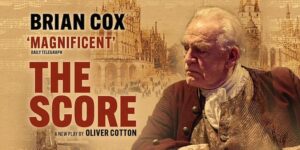

It was Frederick who gave Bach the peculiar theme we now know from Bach’s “A Musical Offering”, which Bach in due course dedicated to Frederick. In 2005, James Gaines’s book “Evening in the Palace of Reason” was a brilliant analysis of the disparate lives of these two men – brilliant because its account of their unalike thinking makes their collision, and Bach’s music, all the more exciting. Now the same conjunction of luminaries is the subject of “The Score”, a play by the veteran actor Oliver Cotton (who has several plays to his name).

Bach was the master of the fugue; Frederick (with a little help from some other resident composers) has composed a theme that seems “unfuguable”. Cotton’s play falls into two halves. The first is a conventional, charming, and entertaining reimagining of how life was for Johann Sebastian – especially when his orbit crossed that of Frederick (and Voltaire) when visiting his son Carl Philipp Emmanuel in Potsdam. In its second half, however, “The Score” explodes – suddenly becoming both sociopolitical and (subtly) Freudian.

Bach confronts Frederick with the news that, in Leipzig, four of Frederick’s soldiers have raped the blind daughter of Bach’s baker. Frederick replies “These things happen” (“Stuff happens” comes to mind). But Bach will not stop there. Frederick has casually related how the theme that he has given to Bach has kept him, Frederick, awake at nights: Bach suggests that the theme actually expresses and releases the thoughts (politics, guilt, repression, warfare) that have kept Frederick from sleeping. Bach, master of fugue, taps the bass undercurrents that can connect the unconnectable.

Cox, renowned from many screen roles, has often been an over-blustery stage actor in the past, but here he turns that style into heroic virtue. (One of the great pleasures of this Theatre Royal Haymarket production, directed by Trevor Nunn, is that it is apparently unamplified, at a time when microphones are routinely used in even small theatres.) We see how this Bach is a vital force: he can shout – but thrillingly and, indeed, musically. And sometimes, speaking quietly, he is uproarious. Having heard Frederick’s musical theme and discussed its chromatic complexity (in the presence of four other, younger composers), he leaves a long pause – we know that the others have bet four thousand thalers on whether he can or cannot improvise a three-part fugue on it – he says lightly, almost camply, “Well, I might give it a try”, and so brings down the house.

Stephen Hagan makes Frederick an authoritative caricature, almost like George III in “Hamilton”. The usually excellent Peter de Jersey doesn’t quite solve Voltaire (who, admittedly, was at his most conflicted around Frederick), but he makes him both urbane and lucid. Cox’s wife Nicole Ansari-Cox plays Bach’s wife Anna, combining charm and sense. Jamie Wilkes nicely catches the polished embarrassment of Carl Bach, proud of and shamed by his irrepressible father.

“The Score” – which closes at the Haymarket on Saturday 26 – has been drawing attention because of Cox, but it’s a strong enough play to merit revival with other actors as Johann Sebastian. I love the way that Cotton swiftly moves from the hilarity of Bach’s sudden but playful decision to improvise this taxing fugue to a discussion of meaning in music. To Frederick, Bach now says “Your theme is not nonsense. Neither is it written to merely please the ear. It speaks of struggle, or pain and sorrow.” Within a minute, he has moved on to speak of rape and war crimes. Bravo.

The post Fred the Great said: I’ll get Bach to you appeared first on Slippedisc.