|

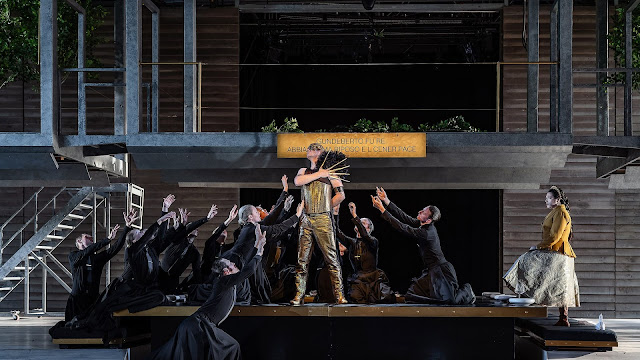

| Handel: Rodelinda – Lucy Crowe – Garsington Opera (Photo: courtesy Garsington Opera) |

Handel: Rodelinda; Lucy Crowe, Tim Mead, Ed Lyon, Brandon Cedel, Marvic Monreal, Hugh Cutting, director: Ruth Knight, the English Concert, conductor: Peter Whelan; Garsington Opera

Reviewed 29 June 2025

With a title role performed with real style and agency by Lucy Crowe partnered by Tim Mead singing with luminous tone there is plenty to enjoy, complemented by an intelligent and imaginative presentation of some real drama

Unlike some Baroque operas, where narrative logic takes second place to the creation of dramatic situations that put their characters through a series of moral dilemmas, Handel’s Rodelinda has a remarkable focus to its plot. Partly, this is because the drama concentrates on Rodelinda and Bertarido and the piece becomes, effectively, an examination of marital fidelity. Of course, there are logic holes too; in Act Three, for instance, Nicola Francesco Haym’s libretto rather trips up on itself in order to give Rodelinda a scene where she believes Bertarido is dead. But what a scene it is. And that is the attraction of this opera; Handel at his peak writing music allied to a libretto that requires a lot less special pleading than some Baroque operas.

For its new production of Handel’s Rodelinda, Garsington Opera has turned to Ruth Knight for a production that builds on Handel’s focus on the title role by giving Rodelinda real agency. We caught the performance on Sunday 29 June 2025. The English Concert was conducted by Peter Whelan, artistic director of the Irish Baroque Orchestra with whom he performed Vivaldi’s L’Olimpiade with Irish National Opera in 2024 [see my review].

|

| Handel: Rodelinda – Tim Mead, Marvic Monreal – Garsington Opera (Photo: courtesy Garsington Opera) |

Lucy Crowe was Rodelinda with Tim Mead as Bertarido, plus Ed Lyon as Grimoaldo, Brandon Cedel as Garibaldo, Marvic Monreal as Eduige and Hugh Cutting as Unulfo. Designs were by Leslie Travers with lighting by Ben Pickersgill and movement by Rebecca Meltzer.

Travers’ elegant set was based around steelwork that almost seemed an extension of the theatre itself. The look was modern, with a series of balconies and linking upper walkway which imaginatively gave the stage two levels. Costumes were modern, but there was also an element to the exotic too; place and time were nonspecific, though the characters’ obsession with regal regalia (crown, orb and sceptre) placed it at a remove from the contemporary. There was a playful element, when Bertarido is in disguise in Act 2, Tim Mead wore a costume that would not have disgraced Elton John in his pomp, and when Garibaldo made public appearances he wore a mask somewhat similar to something Orville Peck would wear. But the biggest visual stimulus during the opera was the use of 14 dancers who formed a troupe that did Garibaldo and Grimoaldo’s bidding, but also acted as a sort of visual commentary.

Knight told the story well, providing clarity and helping the narrative by including a prologue (during the overture) where we saw the events that led up to the opera’s narrative. But there was a restless element too. The use of the dancers hinted at the idea that Knight was not quite comfortable with an empty stage, the Handelian trope of one singer on stage alone for ten minutes or so. Instead we had a visual commentary; at times, such as in Act Two when the sequence of Marvic Monreal’s Eduige using a pigs head, then both Brandon Cedel’s Grimoaldo and Hugh Cutting’s Unulfo having a full accompaniment of dancers participating in their arias, things did feel over busy but thankfully by the end of that act things had calmed down.

|

| Handel: Rodelinda – Marvic Monreal – Garsington Opera (Photo: courtesy Garsington Opera) |

The drama needed no extra help because Knight and Whelan had drawn such strong and musical performances from the cast.

From the outset, Lucy Crowe made a powerful, intent Rodelinda. There was no doubting her feeling for her husband during the opening aria where Crowe’s plangent tone brought out the intensity of the music, but in her second aria she was all defiance against Ed Lyon’s Garibaldo. And this was a Rodelinda who wore trousers and knew how to use a sword. She might lament the loss of her husband, yet she had real agency. In Act Two, dressed remarkably in Medieval style (with a wimple) in Virginal blue and white, Crowe brought real strength to Rodelinda’s challenge to Grimoaldo (if you want to marry me, kill my son), even to the extent of drinking pigs blood. Crowe brought this all off with real relish, singing with fearsome tone, yet her final aria in the act, when Tim Mead’s Bertarido revealed himself to her, was quietly moving. The third act places Rodelinda on an emotional rollercoaster, there is the wonderful duet with her husband but then his apparent loss (again!) and a powerful aria of lament. The duet with Mead was everything we could wish for whilst Crowe was intensely moving in the aria, pushing everything onto the tone and the music, with little in the way of staging.

Bertarido does get an action aria at the very end of the opera when he lets Grimoaldo live. But for much of the time, the role displays the first Bertarido, castrato Senesino’s penchant for the ‘pathetic’ in 18th century usage. He is initially somewhat passive, with a pastoral element, along with a willingness to think the worst. The advantage was that Tim Mead sang this music so beautifully, from the opening notes of his first aria with the messa di voce on ‘Dove sei’ we knew that we were in for a treat. Mead brought a luminous quality and an intensity to Bertarido’s music, so that his character felt rather less of a wimp. There was real depth to his feelings in Act Two when he believes Rodelinda is unfaithful, and the connection between Mead and Crowe was palpable at their reconciliation in Act Two and the duet in Act Three. Then Mead gave us heroic tone and real bravura for that final aria. Bertarido is never going to be an action hero, but here he felt a lot less passive. His appearance in disguise in Act Two, with a smoke-filled entrance reminiscent of a rock concert was at some remove from the pastoral nature of his aria, but Mead brought this off brilliantly.

|

| Handel: Rodelinda – Brandon Cedel, Ed Lyon – Garsington Opera (Photo: courtesy Garsington Opera) |

Grimoaldo is a weak, vacillating character. To this Ed Lyon brought a heavy dose of charm too, his Grimoaldo seemed to think he could get whatever he wanted through personality alone. His attempt to be overbearing in Act One failed, and for his wedding in Act Two his outfit was almost laughably over the top. If he wasn’t so vicious, this Grimoaldo would have been a pitiable figure and it was part of Lyon’s skill that he managed to walk the fine line between the two; vain, vicious and vacillating, a fatal mix. Vocally Lyon had the right combination of power and flexibility in the voice.

The power behind the throne was Brandon Cedel’s Garibaldo, strong and resonant of tone, with a nice sense of bravura where necessary, Cedel brought real focus to the character, there was no black and white. He very much projected ‘hard man’ sex appeal, and his seduction of Monreal’s Eduige in Act One was masterly, but it was followed by a solo where Cedel brought out the real blackness in Garibaldo. There was a control about him and his body language, in his vivid aria in Act Two it was the dancers who swirled around, articulating the music.

Bertarido’s sister Eduige can be a somewhat sorry character, always mooning after the wrong man. Here she was firmly a secondary role, yet Marvic Monreal brought strength to her performance, and with a vividness to Eduige’s various swings of humour, from vowing revenge on Grimoaldo in Act One, to her remarkably vicious aria in Act Two with its use of a pigs head; a real bravura performance. Yet Monreal was touching in her reconciliation with Mead’s Bertarido at the end of Act Two.

Unulfo is a secondary role, one where the arias can often be cut and it has to be admitted that none of them take the plot forward in any way. But when you have a singer of the quality of Hugh Cutting in the role, it makes sense to include all three. And Cutting sang with great beauty of tone, investing his simile arias in a real depth of meaning. Yet his performance had puckish quality too in the way that his Unulfo has agency, it is he that orchestrates things in the background.

Nicholas Thurbin who played the silent role of Flavio, Rodelinda and Bertarido’s teenage son, had a rather bigger role than is often the case, and Thurbin played it admirably.

|

| Handel: Rodelinda – Hugh Cutting – Garsington Opera (Photo: courtesy Garsington Opera) |

Orchestrally, Handel uses only flute/recorder, oboe and bassoons in addition to strings and continuo, yet Peter Whelan and the orchestra found real tonal riches in the music. Whelan managed to conjure some wonderfully rich sounds from his players, whilst providing admirable support to the singers. Musically this was a very strong performance, with a soloists who were all fine stylists sympathetically partnered by Whelan and the orchestra. The continuo of two harpsichords (Whelan and Ashok Gupta), theorbo (Sergio Bucheli) and cello (Joseph Crouch) provided variety and imagination, whilst the recitatives kept up in a nicely pacey manner.

This was an evening that seemed admirably free of gimmick. There was little sense of that element of crowd pleasing that can creep into Handel’s opera seria. Everything was here for a reason, yet done with a vivid sense of style and stagecraft that made the stage performances all the more compelling, supported by strong musical performances from some of the best Handel singers around.

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- A different focus: Timothy Ridout in Mozart & Hummel with Academy of St Martin in the Fields plus Rossini & a Weber symphony – concert review

- From Handel to Verdi & beyond: Soraya Mafi on singing in Handel’s Saul at Glyndebourne, expanding into bel canto & Bernstein – interview

- An alternative way people can encounter classical music: Baldur Brönnimann & Felix Heri introduce Between Mountains Festival – feature

- The BBC Symphony Orchestra’s visit to this year’s Aldeburgh Festival – concert review

- Brilliant reinvention & razor sharp take-down: Scottish Opera’s double-bill pairs Gilbert & Sullivan with Toby Hession’s brand new comedy – opera review

- A trio of concerts at this year’s Aldeburgh Festival highlights the diversity of music to be found on the Suffolk coast – concert review

- That was quite a party! Paul Curran’s production of Die Fledermaus at The Grange Festival is a terrific evening in the theatre – opera review

- Modern resonances & musical style: Richard Farnes conducts Verdi’s La traviata at The Grange Festival with Samantha Clarke & Nico Darmanin – opera review

- Maiden, Mother & Crone: Rowan Hellier on her interdisciplinary project integrating music & movement exploring Baba Yaga – interview

- The Merry Widow meets the Godfather: Scottish Opera brings John Savournin’s production of Lehár’s operetta to Opera Holland Park – review

- Home