|

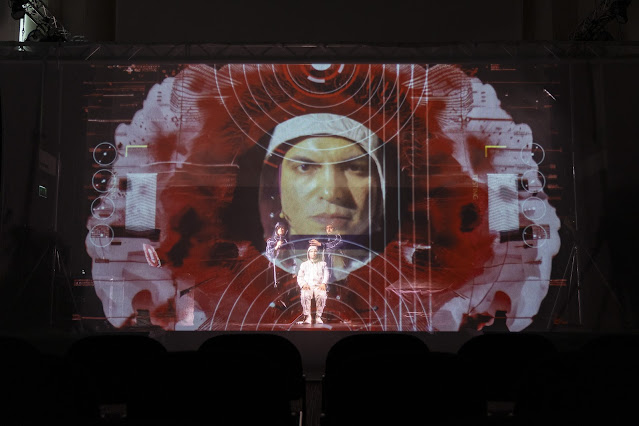

| Alexander Schubert: Steady State – world premiere 7 May 2024 – Zubin Kanga at National Concert Hall, Dublin (Photo: Roisin Murphy O’Sullivan) |

Pianist, composer and technologist Zubin Kanga is known for both his championing of contemporary music as well as his innovative interdisciplinary musical programmes, exploring what it means to be a performer through interaction with new technologies. Zubin has a busy Autumn lined up with four world premières by Laurence Osborn, Alex Groves, Alex Ho and Claudia Molitor, plus a performance of Steady State, a ground-breaking work by Alexander Schubert which expands Zubin’s use of new technologies.

|

| Zubin Kanga (Photo: Raphael Neal) |

On 10 October Zubin will premiere Laurence Osborn’s piano concerto, Schiller’s Piano with the Manchester Collective in a programme entitled Fever Dreams at the Royal Northern College of Music, repeating the programme at the Southbank Centre on 12 October. Osborn’s work calls for Zubin to play both the piano and a keyboard controlling samples. These samples are all sounds that Osborn recorded in the Southbank Centre’s piano workshop where the centre’s pianos are restored and looked after. Thus Osborn has captured the sound of different components being restored, along with visceral sounds from the inside of the piano.

The work is inspired by Osborn seeing a replica of Schiller’s piano. In 1942 the furniture in Friedrich Schiller’s house in Weimar was replaced by replicas, with the originals stored underground. The replicas were made by prisoners in Buchenwald, and when it came to the piano they copied the outside only, it was unable to play music. This replica piano is now at Buchenwald, and in writing Schiller’s Piano, Osborn has responded to fascism’s empty attempts to recreate the past. Osborn came to Zubin with the concept for the piece and the two were in frequent contact as Osborn was writing it. Zubin describes Osborn as writing virtuosic piano music, so there were practical considerations related both to the physicality of playing two keyboards and the timing of the sounds from the different sound worlds. There were plenty of technical intricacies and they spent six months working on the piece, and when I chatted to Zubin they were still working on details.

This type of collaboration with the composer is what Zubin always does with a new work. He likes collaborating and feels that it is good for the performer to be part of the creation process and in fact, wrote his PhD on the topic! When working with new technology this becomes even more important, especially as they might need to get advice about the technology itself.

The concerto was commissioned by Zubin Kanga and Manchester Collective as part of Cyborg Soloists, Zubin’s multi-year project at Royal Holloway University of London which is exploring working with new technology. As part of Cyborg Soloists, Zubin has lots of technological partners enabling him to work with a variety of new technologies. At the Aldeburgh Festival this Summer he played an instrument with hexagonal keys with a 31-note microtonal scale, and he rather dryly commented that he needed time to learn the instrument. There is always new technology coming along and Zubin has to not only physically learn to play the new instrument but learn how to make it work in a musical context.

|

| Replica of Schiller’s piano in Buchenwald’s exhibition Ostracism and Violence 1937 to 1945 (Photo: Katharina Brand, Collection Buchenwald Memorial) |

An example of his innovative approach is his espousal of technology developed for medical purposes. At hcmf// (Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival) on 18 November, Zubin will perform Alexander Schubert’s Steady State which features the world’s first decision-based use of brain sensors to control music and video. For the work, Zubin is hooked up to an EEG cap measuring dominant resonant frequencies in the visual cortex. These sensors utilise a feature of the brain understood and used by neurologists, that if we watch a flashing light, the same speed can be detected at the back of the brain. This is used to control prosthetic and language software, but in this case, they are putting the data into music software. Though the technology has been around for a while, they had to develop the performance usage from scratch.

In performance, Zubin will have a hologram screen in front of him with things flashing at different speeds on the screen, depending on where he looks, this controls what happens, and there is a feedback loop whereby what happens affects what is on the screen. He describes the first part of the new work as akin to a scientific or science-fiction experiment, and this includes an explanation for the audience, whereas the second half is more free-form.

The next day at hcmf//, Zubin will premiere Alex Ho’s Cyborg Etudes in a programme that also includes Claudia Molitor’s In Den Träumen and Alex Paxton‘s Car-Pig. Ho’s piece uses a ring sensor which is a 3D sensor which Zubin has used before and he has also used glove sensors. The sensor detects where on the piano his hand is, and what his hand is doing, and thus his hand position controls delays which affect the sound and the live video, thus responding to what Zubin’s hand is doing. The result is live effects, with the effects being carefully chosen, and just as with playing the piano, the sound will change each time he performs the piece. He feels that this makes Ho’s work rather closer to working with live electronics, and he is trying to get away from something too fixed like an electronics track in the background. Also, the ring makes the performance more theatrical as the performer controls everything with a sense of theatre, as opposed to performances which use a second person simply controlling the live electronics from a laptop at the side of the stage.

With both the Ho and the Schubert, there is an old-fashioned sense of theatre to Zubin’s approach, and a lot of his performances are about the physicality of performance, and he is trying to get back to that sense of embodied sound. So, rather than disembodied electronics alongside his physical keyboard playing, the new technology enables him to give the illusion of embodied sound, the electronic sound connects to bodily gesture. Even Osborn’s concerto has a traditional element, as for Zubin it is still a piano concerto, albeit one with an extra instrument.

After Zubin’s Southbank Centre performance of Laurence Osborn’s concerto, Zubin will give a solo set After Dark, featuring Tansy Davies’ Star-Way, his own piece Hypnagogia (after Bach) and the world première of Alex Groves’ DANCE SUITE. Groves’ piece is described as ‘a microcosm of queer dating, dance floors, social lives and the role that music has to play in that scene – as a meeting space, place of release, abandonment and connecting with queer people’. Zubin describes it as the sounds you might hear in a nightclub along with Groves’ own versions of music from electronic albums, so familiar but with a twist, all played on keyboards.

Zubin will be playing DANCE SUITE on a Roli Seaboard, which Zubin describes as a keyboard where the keys are so you can move your hand across, up and down and each movement affects the pitch and timbre. He adds rather strikingly that you get these effects by ‘kneading’ the instrument. The technology and the instrument have been around for some time but not used in so much in classical music, however, Zubin has incorporated its use into some of his projects as part of Cyborg Soloists.

Zubin is Senior Lecturer in Musical Performance and Digital Arts at Royal Holloway, University of London, and Cyborg Soloists, his multi-year music and research project, is funded by the £1.4 million UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship. Most of these fellowships are in science and technology and when he was awarded his grant in 2020, his project was one of only three to be awarded to a music-focused project out of 481 fellowships. Cyborg Soloists was established to explore the interdisciplinary interactions between music, the other arts and new digital technologies, using Zubin’s earlier projects from 2015-2020 – Dark Twin, Cyborg Pianist and Piano Ex Machina – as the basis for huge leaps forward in how musicians work with technology.

So Cyborg Soloists involves creating new works, but also involving creative partners and industry partners to explore new avenues, new instruments and new technologies, the use of AI and new approaches. Zubin describes it as an amazing opportunity and it has allowed him to commission around 50 pieces involving a huge number of new technologies. Laurence Osborn’s Schiller’s Piano is one of the biggest projects so far. But there is a big-ness to Alexander Schubert’s piece also, as it involves Zubin and two assistants, as well as having been years in the making owing to the complexity of the technology.

Other works included Philip Venables‘ Answer Machine Tape, 1987 which used a keyboard scanner with typed text on a screen, involving the first use of a device developed by Professor Andrew McPherson of Imperial College and Augmented Instruments Laboratory. Then there was a big piece by Neil Luck which was written with a deaf performance artist, with Zubin using sensor gloves to mimic the gestures of the performance artist and create sounds. Having broken ground with these various technologies, Zubin hopes that others will use them and that the fruits of Cyborg Soloists will be an arsenal for composers and performers to draw up.

|

| Zubin Kanga (Photo: Raphael Neal) |

Zubin trained as a classical pianist, studying at University in Australia where he was involved in performing contemporary music by students, but also performing big works from the piano canon from Bach’s Goldberg Variations through to Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit. Then coming to the UK, he studied at the Royal Academy of Music where he had two teachers, pianist and composer Rolf Hind, and pianist Kathryn Stott. He performed a wide range of music, all on the piano, including a wide exploration of extended techniques including works by George Crumb. He also commissioned a lot of music.

But he felt that he reached the end of what extended techniques on the piano could give, and in 2013/14 decided to do a whole recital using electronics, this was Dark Twin. He was amazed at how it expanded what was possible in performance. His continued academic work, basing his research on pieces he was doing and his grant for Cyborg Soloists was the logical extension to this, using technology to push beyond what is possible on a piano.

All the pieces this Autumn are notated, even the Alexander Schubert, though in Alex Ho’s piece, some of the gestures are up to Zubin, and of course, they need to find a notation for the new instruments. He still plays Chopin, Ravel and Debussy for himself, but he also uses classic repertoire to demonstrate to composers, to show that a lot of techniques have already been explored and that it is great to learn from the past. Once the Cyborg Soloists project is finished, he feels that he may go back to programmes combining old and new, for instance, he once created a programme pairing Elizabethan keyboard pieces with modern reinterpretations, and he finds the idea of modern pieces inspired by the past rather appealing. But he does rather have his hands full at the moment.

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Compelling performances: Stephen Hough, YL Male Voice Choir, Santtu-Matias Rouvali and the Philharmonia – concert review

- Investing in the magic of Purcell’s music: The Fairy Queen from The Sixteen at Cadogan Hall – opera review

- High-quality music-making & imaginative programming in the special natural setting of Exmoor & Dartmoor: I chat to Tamsin Waley-Cohen of the Two Moors Festival – interview

- A superb sense of community: Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana at Blackheath Halls Opera – opera review

- Remembrance and renewal: Peter Seabourne’s My Song in October – record review

- Both audience & player go on a journey together: Latvian pianist Reinis Zariņš discusses Messiaen’s Vingt Regards which he performs at the London Piano Festival – interview

- Celebrating Jommelli in style: Ian Page & The Mozartists make a compelling case for this neglected music – concert review

- Fire and water in the library: Siren Duo in an imaginative flute and harp recital for Temple Music – concert review

- An interview with the Snow Maiden: I chat to Ffion Edwards about taking on the title role in Rimsky Korsakov’s opera with English Touring Opera – interview

- A journey of remarkable emotional depth: Laurence Kilsby and Ella O’Neill at Wigmore Hall – concert review

- Home