This is properly musicians in sevice of music. The pieces here ae rarely heard, and of the three composers only one has anything like the recognition he deserves, and even then it’s somewhat lacking (Bliss). teh Wigmore Soloists’ line-up contains the names of some of the finest alive musicians in the UK today: Michael Collins, Isabelle van Keulen, Rachel Roberts, Robin O’Neill, the list just goes on …

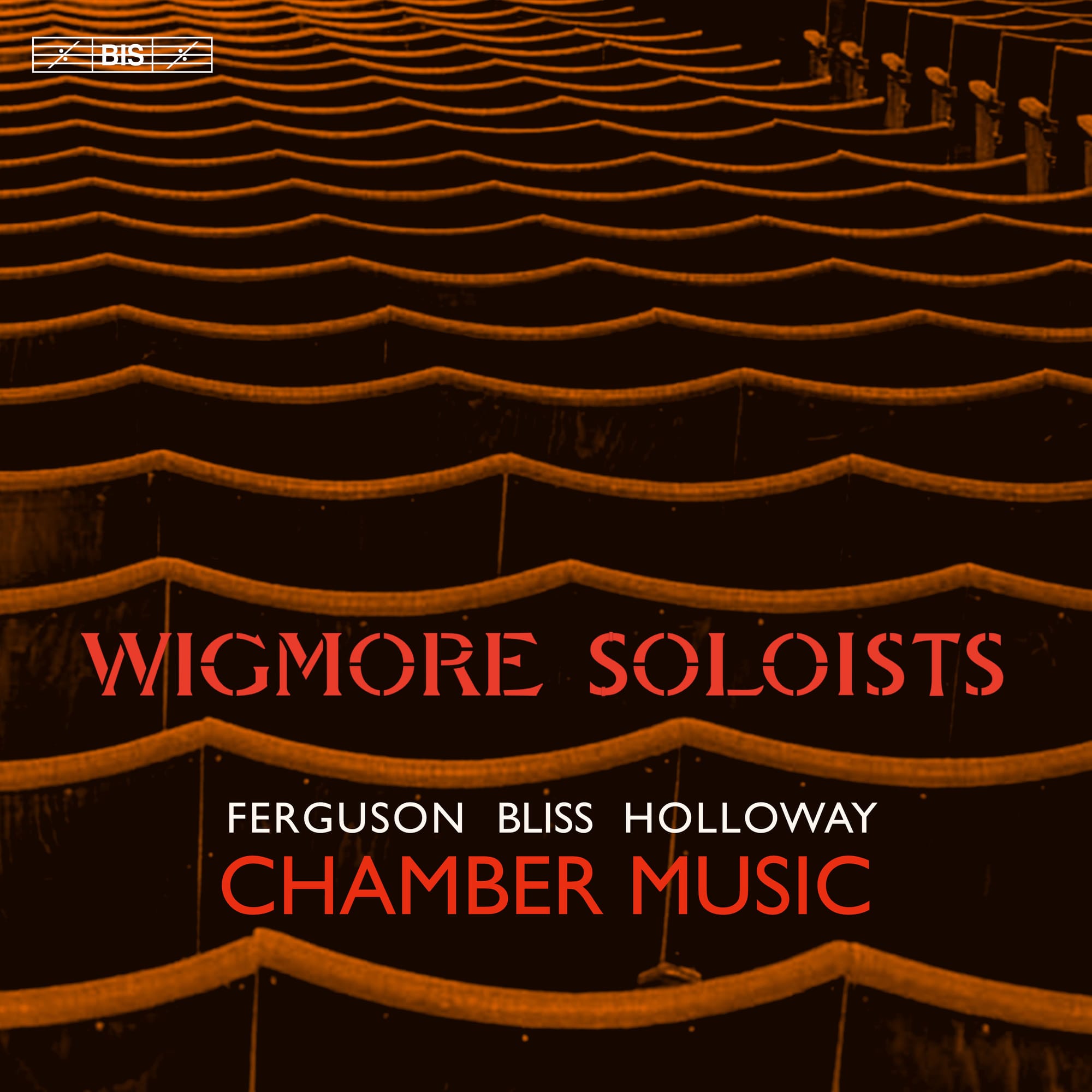

Following their critically acclaimed albums of Schubert (BIS-2597), Mozart and Birchall (BIS-2647), works for clarinet trio (BIS-2535) and, more recently, Beethoven and Berwald (BIS-2707), the Wigmore Soloists now turn their attention to twentieth-century English chamber works which, while eschewing some of the continent’s modernist tendencies, are both deeply personal and supremely written, highlighting the specific colours of each of the instruments.

The Howard Ferguson, his Octet, Op. 4 of 1933, is absolute magic, nowhere less so than in the finely-wrought slow movement, the harmonies dissonant and yet cradled within tonality. This was the first of Howard Ferguson’s works to gain attention; its instrumentation is that of Schubet’s Octet.

The work is dedicated to R. O. Morris (he of the harmony and counterpoint textbooks), The opening Moderatto is involving in its finely-wrought processes – five minutes of (pardon the pun) bliss. Much is clarinet-led (Michael Collins, no less), and one theme has its roots in the famous horn theme from Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony:

The Scherzo buzzes maximally. This is a virtuoso performance that nonetheless preserves the essence of Ferguson’s language. The final fanfares hustle awards a dismissive desire that leaves space for the Andantino, surely the heart of the work, Ferguson in English Pastoral mode. The performance is supreme: all instruments are absolutely equal (listen to how the horn and clarinet statements mirror each other perfectly, with no tase of awkwardness in horn player Alberto Menéndez Escrribano’s statement):

The finale blazes (it is Allegro feroce, after all). A rondo, it also refers back to the themes of earlier, including hat chaikivsky-derived gesture. The players are of such excellence that high-lying, rapid passages that could so easily feel scrappy make perfect sense:

So to that Bliss, the Clarinet Quintet on 1932, inspired by the great clarinettist Frederick Thurston (although the work is dedicated to composer Bernard van Dieren). This also opens with a Moderato, here full of lush melodies, the harmonies adding spice:

The Allegro motto is a whirligig of activity, and again this performance is superb in its maintenance of detail at all levels, captured in a stunning recording.But this movement also has passages expansive enough almost suggest a slow movement (one is interrupted by a final swirl of activity to close the movement):

The flowering of lyricism truly happens the slow movement proper, through an Adagietto espressivo that finds Michael Collins’ clarinet agile, heartfelt and glorious:

The finale dances in sprightly fashion:

Fascinating to have some Robin Holloway here, his Serenade in C, Op. 41 (1979). Like the Ferguson, it mirrors the scoring of Schubert’s Octet. The piece is fascinating: there is a light touch, but the capricious nature of the writing and indeed the language adds real depth. It all feels right, and yet is unpredictable. This is a masterly piece. There’s a cruel horn solo in the first movement (‘Marcia’) shortly after three minutes in that is radiantly played by Sánchez.

The Menuetto alla tarantella may be unique in its design, but it is also mightily impressive. There is arguably more virtuosity for clarinet in this movement than in the Bliss (which specified the clarinet as soloist), and once more Collins is magnificent. A melodic Trio has its lyricism ameliorated by angularity:

Th slow movement is a set of variations Holloway found in an old Methodist hymn book. That might seem out of place in a serenade, but Holoway was attracted to the “sincere, naïve” quality of the melody – which qualities, of course, make it ripe for variations. e

Holloway offers a ‘complementary’ Minuet (the composer’s own words) to the first, this on earth-bound, almost martial. Repeats begin as if classically derived (so, literal) but then tend to veer off, unexpectedly. his ‘playing with form’ and/or expectations seems to be a core part of Holloway’s composition.

A tarantella returns for the finale, the clarinet’s tune winding round itself deliciously like ivy:

A fabulously interesting disc. It is doubtful any of these pieces have been bite seven on disc.