|

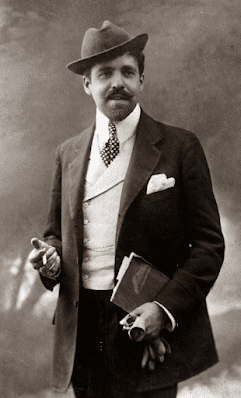

| Reynaldo Hahn in 1906 |

Songs by Reynaldo Hahn; Maria Schellenberg, Jack Holton, Nigel Foster; London Song Festival at Hinde Street Methodist Church

Reviewed 8 November 2024

Over 20 of Hahn’s best known songs in a comprehensive programme that illuminated his early career as a remarkable (and prodigy-like) song composer

The London Song Festival‘s Autumn 2024 season is celebrating the Class of 1874, composers, poets and a singer all born in 1874. On 8 November 2024, at Hinde Street Methodist Church, it was the turn of Reynaldo Hahn, as pianist and festival director Nigel Foster was joined by mezzo-soprano Maria Schellenberg and baritone Jack Holton for a programme of Hahn’s songs.

It is intriguing to compare two of the composers featuring in the festival, Reynaldo Hahn and Gustave Holst. Holst like his friend and contemporary Vaughan Williams (born 1872) took time to find his voice and his significant music all dates securely from the 20th century, whereas Hahn was talented early. One of his best known songs Si mes vers avaient des ailes was written when he as just 14 and the majority of the evening’s songs were written in the 19th century. Whilst the older Hahn would change his style, somewhat, to reflect the 20th century he was always a rather backward-looking figure and in many ways it is fascinating to realise that he was Holst’s exact contemporary, especially when you realise that two other contemporaries are Arnold Schoenberg and Charles Ives (both also born in 1874).

Hahn’s teachers included Massenet (born 1842) and Saint-Saens (born 1835), neither of whom are renowned for their advanced techniques and Hahn’s song-writing in particular remains firmly linked to the Belle Epoque. Hahn became a friend of the playwright Alphonse Daudet, writing music for one of Daudet’s plays when he was just 16. And it was at Daudet’s house that Massenet’s muse, soprano Sybil Sanderson premiered Hahn’s Chansons Grises, his first published songs.

Age 19, Hahn began a two-year relationship with Marcel Proust (then aged 22), which would be one of Proust’s few developed relationships. They remained friends and collaborated on Portraits de Peintres, a work for reciter and piano that would be intriguing to revisit today. To give an idea of quite how inbred the whole ethos of the artistic circle was, Hahn’s replacement in Proust’s affections was Lucien Daudet, Alphonse Daudet’s son.

Hahn wrote around 100 songs, most of which date from the period 1888 to 1918, and few date from after 1910, as society was changing and he found less demand for songs with piano and his compositional energies were more devoted to his theatrical works, his music theatre works (opera, operette, musical comedy) number some 15 or so, with several ballets as well.

Nigel Foster’s programme concentrated on the favourite songs, adding a few novelties but 1906 was the most recent of the songs, though the evening ended most delightfully with the duet, La Derniere Valse from a 1926 musical comedy. You feel that the 20th century Hahn might be worth investigating; in 1915 he set English texts in Five Little Songs with verses by Robert Louis Stevenson and his final song cycle, Chansons espagnoles dates from 1947, some 59 years after his first songs.

Foster divided the programme into thematic sections. Desires: Fêtes galantes, Les cygnes, Desires and Love: À Chloris, En Sourdine, Quand je fu pris au pavilion, Si mes vers avaient des ailes, Love and Death: L’énamourée, Trois jours de vendange, Night: L’heure exquise, La Nuit, Lovers united in death: Dernier voeu, Three Cities: La Barcheta, Seule, Encor sur le pavé sonne mon pas nocturne, River and Sea: Dans la nuit, Quand la nuit n’est pas étoilée, Sur l’eau, Paysage, Autumn: L’Automne, Chanson d’Automne, The Passing of Time: D’une prison, Fleur fanée, La Derniere Valse.

Given the early age at which some of the songs were written, Hahn had quite sophisticated literary tastes and tackled some very complex subjects. His setting of Verlaine’s L’Heure Exquise was completed when he was 16, whilst another Verlaine setting, D’une prison dates from when Hahn was 18. Clearly teenage Hahn enjoyed a great deal of angst, imaginings of desire, death and impossible love. Whether this was genuine or an assumed attitude is an interesting point, he was singing in salons when he was six, his friendship with Alphonse Daudet began he was just 16.

Our two singers alternated the songs, joining together for Dernier voeu at the end of the first half, and La Derniere Valse at the end. Maria Schellenberg had a rich, dark mezzo-soprano voice and she brought remarkable depth to the songs, yet she could lighten the textures too. She displayed a stately charm, and her characterful performances were illuminated by her histrionic skills, she is not a singer to simply stand and deliver. Face, body and hands with long nails were all brought into play and each song became a mini-drama; L’énamourée and Dnas la Nuit became positively operatic in their delivery.

Many of Hahn’s songs feature memorable but not elaborate vocal lines over a moving piano, but Schellenberg’s performances were not simply about the music. In a song like À Chloris, she was not content to simply bask in the beauty of the melodic line. She gave attention to the words, making each song a mini-narrative. She featured as a somewhat heavier voice than I am used to in La Barcheta from Venezia which I first heard sung by a lyric tenor, but she made the song more consistently seductive. Encor sur le pavé sonne mon pas nocturne was a truly remarkable song, the voice almost a monotone, written in 1901 its darkness was more complex than the attitudinising in some.

Jack Holton displayed a dark, almost chestnut toned voice and his rich sound gave a gravity to his performances, and many of his early songs in the recital featured some of Hahn’s minimal melodies, to which Holton brought gravitas and depth, along with a real feeling for the sound of a French baritone.

So that the calm line if En Sourdine was rendered profoundly expressive, and the opening of Si mes vers avaient des ailes had a sober solidity to them, before shading into real passion, whilst Trois jours de vendange ended on a sober, but profoundly expressive monotone with bells in the piano. La Nuit featured a richly expressive sense of darkness and the song was written when Hahn was just 17. In his final solo of the evening, Chanson d’Automne Holton drew on a vein of seductive melancholy in what is a rather haunting melody.

The performances made us realise that Hahn’s songs are much more than a guilty pleasure and that there is a remarkable sophistication in their apparent simplicity. I would perhaps, have liked an element of grit to the mix, but then Hahn didn’t really do grit, did he?

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- The sound of wind, sunlight or water: pianist Anna Tsybuleva on her new recording of Debussy’s Préludes on Signum Classics – interview

- A bright beginning: Three Sonatas reveals the distinctive voice of young composer Sam Rudd-Jones in chamber music that intrigues – record review

- Provoking the inner senses: Mendelssohn’s Elijah in the majestic surroundings of King’s College Chapel, Cambridge – concert review

- Gentle Flame: Liz Dilnot Johnson’s diverse output showcased in this disc celebrating her relationship with Ex Cathedra – record review

- Forging ahead: Specializing in the performance of Wagner operas, the London Opera Company in Siegfried – opera review

- A terrific achievement: professionals & amateurs come together at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre performing Jonathan Dove’s The Monster in the Maze in celebration of Music in the Round at 40 – opera review

- Fauré and Friends: I chat to violinist Irène Duval about her explorations during the composer’s centenary celebrations – interview

- The Heart of the Matter: rare Britten and new James MacMillan in an imaginative programme for tenor, horn and piano – concert review

- The Turn of the Screw: Charlotte Corderoy’s notable conducting debut at ENO with Ailish Tynan’s compelling performance – opera review

- An engaging evening of fun: demonstrating the very real virtues of Gilbert & Sullivan at its best, Ruddigore at Opera North – opera review

- Home