Leslie Korngold is the grandson of composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Leslie’s father, George, himself a record producer, was the composer’s younger son. When George Korngold died in 1987, Leslie inherited George’s archive of family recordings. Amongst these, rather amazingly, are private recordings of Korngold performing his own music. Supertrain Records is issuing a two-CD set consisting of Korngold’s Symphony in F sharp, Op. 40, recorded in 1997 by John Mauceri and the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana, along with Korngold’s own piano performance of the symphony recorded between 1952 and 1954.

This is the first time that Korngold’s piano recording has been released commercially. Leslie explains that small sections of it were included in a video documentary many years ago, however, the recording in its entirety has not been heard in Leslie’s lifetime, and he credits Lance Bowling of Cambria Music, who did the digital restoration, and conductor John Mauceri with helping to bring the recording to light.

Leslie was aware that recordings existed, he had seen the physical recordings in his father’s studio but had never heard them. When he inherited the family archive, it was a few years before he had time and leisure to explore it. It was quite a process of discovery and he met his grandfather through his grandfather’s recordings, along with some surprises including the Symphony on acetates recorded by the composer in Hollywood between 1952 and 1954. They were not specifically marked, not notable, until the needle dropped and he heard them, and it was jaw-dropping.

Korngold’s piano recording of his symphony was, in fact, not the first discovery. Sometime before, John Mauceri was preparing to perform Korngold’s Symphonic Serenade and he asked Leslie if there were any materials. What Leslie found was his grandfather’s piano recording of the Symphonic Serenade. So, when John Mauceri was preparing Korngold’s Symphony he contacted Leslie and said he had an impossible thing to ask. Was there anything relating to the Symphony?

By this time, Leslie had prepared a database of all the recordings; there was so much there that he did not remember what there was. So, he searched, and there was his grandfather’s recording of the Symphony.

The archive, which is now in the collections of the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences as the Korngold Family Collection, contains everything from private family recordings to spoken word recordings from Korngold, his wife, both his sons and even Korngold’s father Julius, and acetate discs from sound stage sessions at Warner Brothers and radio performances. As Leslie dryly puts it, there is quite a bit there, including other recordings of Korngold playing his music. Not quite as dramatic as the recording of the Symphony but there is more.

Leslie has a strong desire that the release of the recording will help reshape the narrative of his grandfather’s music. Leslie feels that we should get back to the idea that Korngold was a composer of serious classical music, and that his Hollywood career was just a part.

|

| Front of LP, back of LP, – courtesy of the Special Collections and Photograph Archive, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. |

Leslie says that everyone assumes that he was raised in a house immersed in music and, to a certain extent, this is true. But until his father, George, started recording Korngold’s music, the films first then the operas and concert music, Leslie had never heard his grandfather’s operas and concert music. The vast majority of Korngold’s music that the young Leslie heard was when his father came home with a 16mm print of one of the films his grandfather wrote the score for. Portions of the operas were recorded on 78s, but these were not something that was played at home. It was only in the 1970s that the film music recordings opened the door for them to hear the greater works.

In the 1960s and 1970s, live performances of Korngold’s music were somewhat limited, and Leslie comments ‘how it has changed now’. There are so many concert performances of Korngold’s music and there is nothing like hearing his music live in the concert hall. By bringing the historic recordings to life, Leslie hopes to bring greater interest in his grandfather’s music.

Leslie sees it as a positive thing that repertoire is changing and widening in concert halls, and the UK has done a lot to promote Korngold’s music. The Violin Concerto is now something played by everyone, and he comments about the Berlin Philharmonic performing it in New York. However, with Korngold’s Symphony, there are too many preconceived notions. Hearing the work played by Korngold himself, Leslie hopes will reset the tone of approaches to the piece, alongside John Mauceri’s informed recording.

These are important tools to help reset the view of Korngold. Leslie wants people to judge the music for what it is. For a long time, the Violin Concerto was considered a Hollywood concerto, old descriptions refer to it thus, and we need these stereotypes to go. The Symphony comes late in Korngold’s career and is very different, it lets us appreciate how his career developed.

For Leslie this is an exciting project; music was not his career path, it is an honour but a bit humbling to be involved. Korngold’s talents speak for themselves whilst his father George was influential. For Leslie to have a small part in the project is a privilege.

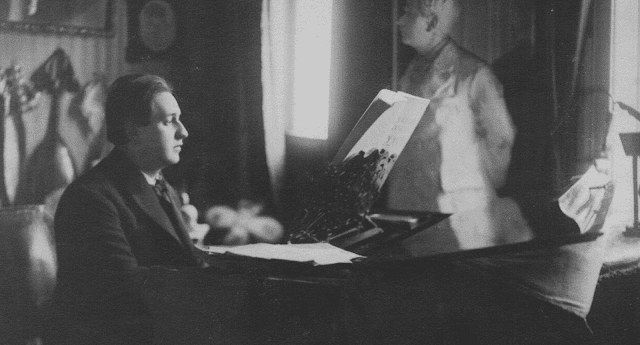

|

| Korngold at the piano – courtesy of the Leslie Korngold Collection |

Korngold was highly recognised in his lifetime, both pre-Hollywood and during the Hollywood period. Korngold’s last Hollywood film score was Escape Me Never (1947) and then for the final ten years of his life he concentrated on concert pieces, including the Violin Concerto, Symphonic Serenade for strings, Cello Concerto and the Symphony. Suddenly, after his death, the switch was turned off. Classical music, Leslie comments, has become compartmentalised, and we should realise that Korngold’s music is different, but not lesser.

The Korngold Symphony is on Supertrain Records featuring Erich Wolfgang Korngold (piano), and Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana, conductor John Mauceri. STR062

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- Between Friends: a new disc of Jonathan Dove’s music celebrates friendship & collaboration in music – record review

- The Uncanny Things Trilogy: Virtually Opera’s trilogy of interactive, immersive operas created by Leo Doulton – photo essay

- Missed opportunity: Christoph Marthaler’s reworking of Weber’s iconic Der Freischütz redeemed by strong musical performances from Opera Ballet Vlaanderen in Antwerp – opera review

- Power & poetry: all-Prokofiev programme from Igor Levit, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer at Royal Festival Hall – concert review

- The disc is worth getting for the Liszt: throw in Holmès & de Grandval & you have a winner, le vase brisé from Thomas Elwin & Lana Bode – cd review

- Everyone in the group feels strongly about it: Harry Christophers introduces The Sixteen’s 25th Choral Pilgrimage, Angel of Peace – interview

- The cast were clearly having fun whilst the plot was made satisfyingly coherent: Mozart’s The Magic Flute from Charles Court Opera – opera review

- Symphonic Bach: the St Matthew Passion in the glorious Sheldonian Theatre made notable by strong individual performances – concert review

- A very personal vision indeed: Mats Lidström in Bach’s Cello Suites as part of Oxford Philharmonic’s Bach Mendelssohn Festival – concert review

- There was no plan, it just happened: violinist Ada Witczyk on the Růžičková Composition Competition and her New Baroque disc – interview

- Home