Contents:

The Chosen: For What? by Hana Gubenko

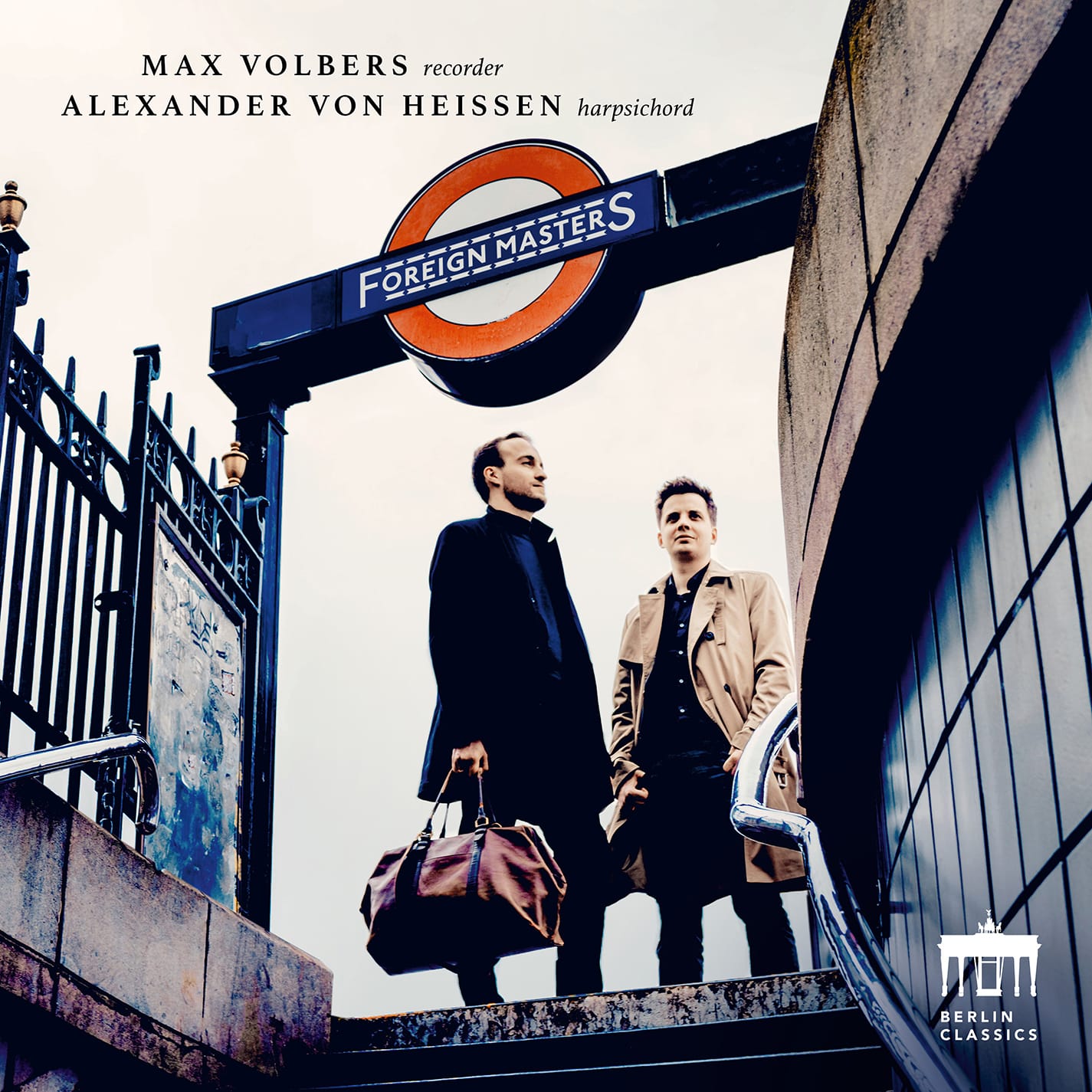

Foreign Masters: Max Volbers and Alexander von Heissen play music by foreign composers in Baroque England, by Colin Clarke

The Chosen – for what?

Who wouldn’t want to be in the chosen few? Be it a golf club, gym or classical music festival, exclusivity always charms. Is it really the music that drives one to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth, or is it the atmosphere of the cognoscenti that flatters our vanity? This social climbing has caused no end of trouble.

Yet the wish to be inclusive, always with the best intentions, can also play us false. Before we know it, we are tolerating intolerance. The spectre of the Holocaust seals western eyes and ears and lips to genocide in Gaza, and speaking the word can end a career. A society supposedly progressive, tolerant and principled places us beyond the pale.

We all long to belong, if not to an elite then at least to an identity, to be accepted for what we stand for and what we truly are. Music, though, is no respecter of persons but a force of nature, a fifth element – perhaps, to paraphrase a song, the ‘something in [our] veins bloodier than blood’. It pulses through the spirit and up into the ether. How could elitism possibly have a place? Is music a marker of status, a space reserved for ‘our kind’? No, and it never was! We all need shelter, nurturing and love. Prometheus sacrificed his liver to give humankind warmth, and music should be as accessible as oxygen and electricity. Whatever our education, social rank, or origin, we are equal before loneliness, love, and death. Naked we are born, and naked we die.

Make love not war said the unwelcomed hippies. In the end, we all want to – in Bayreuth or Bahia or Bamako, music is love, and anyone who enjoys it with us becomes a friend. So if an elite wish to remain exclusive, let them go straight to Mars. There they can have candlelight dinners and recitals of Bach from their own chosen musicians, picked for the purpose from the doomed earth.

The rest of us can stay here, in the dirt, the smoke, the cataclysms and the viruses, with our wine, our music, our books and our sense of humour – a community of equals, for richer or poorer, for better or worse. If music be the food of love, play on…

Foreign Masters: European Composers in 18th-Century London

The album Foreign Masters celebrates the profound influence of immigrant composers on 18th-century London. Max Volbers, a prizewinner of the Deutscher Musikwettbewerb as well as the OPUS-Klassik, is our guide.

Then, as now, London was a mixing pot of nationalities, and that provided fertile ground for the development of musical repertoire – here, we focus on the effects it had for the recorder.

We came across our guide, recorder player Max Volbers, perviously on Classical Explorer via his Whispers of Tradition: (re-)inventions for recorder disc.

Handel’s presence in and his influence on London cannot be underestimated. In the operatic sphere alone he dominated (his tenure included a fascinating rivalry with Porpora). The great composer first visited London in 1710, but settled there two years later

So it is with Handel we begin, his seven movement Sonata in B-Minor for recorder and basso. A bit of explanation: this is HWV 367a. Composition date estimates vary quite widely the booklet notes here suggest 1712, while IMSLP thinks around 1724, over a decade later. Originally in D-Minor, it is performed here in B-Minor on a “voice flute,” a tenor recorder.

The second movement, a Vivace, captures the spirit fo this performance, sprightly and cheeky and yet somehow with touches of the profound – listen to those sudden legato sequential ascents that hint at something else afoot. This is the most overtly“English” movement, which Volbers suggests is a hornpipe:

Both Volbers and Von Heissen are virtuosos in their own right, as you can hear from the third movement Furioso, which positively hurtles along:

Handel’s slow movements really test peformers’ interpretative spirit. The music is full of invention. The Adagio really shows off von Heissen in particular before an Alla breve brings a sense of rhythmic bounce back into the equation (low recorder control very impressive here from Volbers):

But maybe it is the Andante that is most beautiful:

It is fascinating how a piece of music can grip the public’s imagination and just travel. One such piece is the “Descente de Cybelle” from Lully’s opéra Atys (see here and here). Here’s an arrangement for harpsichord by Marc Roger Normand Couperin:

Heard on solo recorder, though, the is markedly more chirpy:

Although he never went to England, Giuseppe Matteo Alberti (1685-1751) exerted his presence here via his publications. His Violin Sonatas were published by John Walsh, and we mea one of them here on recorder: Op. 3/4. A Largo is followed by two Allegros, and it’s the first movement Largo I want to play here for its drama coupled with eloquence. The harpsichord provides the destabilisation:

Despite teh ostensibly Allegro-heavy format, the contrast between the second and third movements works out beautifully.

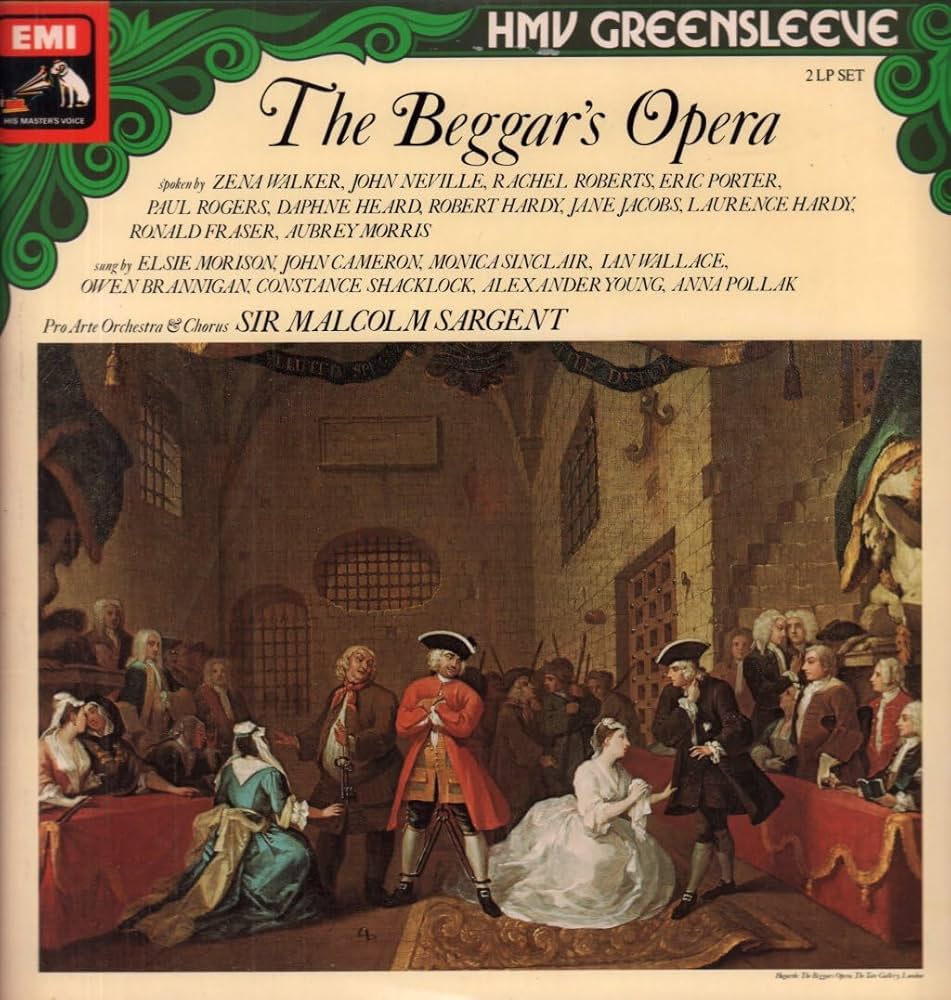

I’m not sure you can get more English than “Cease you funning” from The Beggar’s Opera by Pepusch/Gay:

Here’s the original in the recording I grew up with: Sir Malcolm Sargent and the Pro Arte Orchestra, recorded in 1955:

(Included purely for nostalgia reasons, I grew up with this incarnation, on gatefold double-LP):

Anyway, enough of that. Back to London, and Sammartini, the Sonata in G-Minor, Op 13/5 is performed here on soprano recorder and organ ( harpsichord is also used in this performance), and it works a treat:

William Babell (c. 1690-1723) next, the extended “Vo fa guerra”. Babell was a student of Pepusch’s, so its inclusion makes complete sense..This an extended piece (over ten minutes) and receives a completely convincing performance by Heissen. Here’s a video of him performing it, preceded by a performance of the aria it’s based on (from Handel’s Rinaldo, HWV 7) from Orlinski – you can hear how much the original piece foregrounds harpsichord. Babell’s variations are stunning, and markedly glittering!:

Jaques Paisible (c. 1656-1721) was a name new to me. He arrived in London in 1763, and he was soon renamed “James Peasable”. He was a specialist recorder player, one of the few “full-time”recorder virtuosi of the era. He was known to play diets with Babel. His Suite in A-Minor is a delight, markedly French in demeanour while occasionally veering towards the vernacular of this sceptre’s isle, as you can hear in the this movement “Minuett”:

Giovanni Stefano Carbonelli (1690/91-1772) was a pupil of Handel and published – via John Walsh – a set of 12 Violin Sonatas, although later in life he turned to importing wine, counting the King among his clientele. Here, we have a jolly set of variations from Sonata No. 6 in A. And just listen to Volber’s viruosity at 3″36ff:

Francesco Barsanti (1690-1775) added a bassline to the traditional Scottish melody The Lass of Peatie’s Mill. It is heard here in a haunting performance on a low record that somehow captures, in its slightly breathy tone, the song’s melancholy:

Archangelo Corelli is one of th emore famous names on thsi disc, but I have rarely heard his music played as compellingly as in the second movement of the Sonata Op. 5/12, “La Follia”:

There is an irrepressible rhythmic verve t the finale, too (and just listen to the evenness of the harpsichord!):

I would put this performance up with another special performance we covered on Classical Explorer, the “Christmas Concerto” with Concerto Copenhagen, and Lars Ulrik Mortensen.

It is Alessandro Scarlatti (Scarlatti père, if you prefer) who sends us off to the land of nod with “Vieni o sonno” (which became “Come, O sleep”) from Pyrrhus and Demetrius. It’s rare – and it’s lovely:

Foreign Masters is available on Amazon here. A YouTube podcast between Max Vobers, Hana Gubenko and myself will follow on shortly.