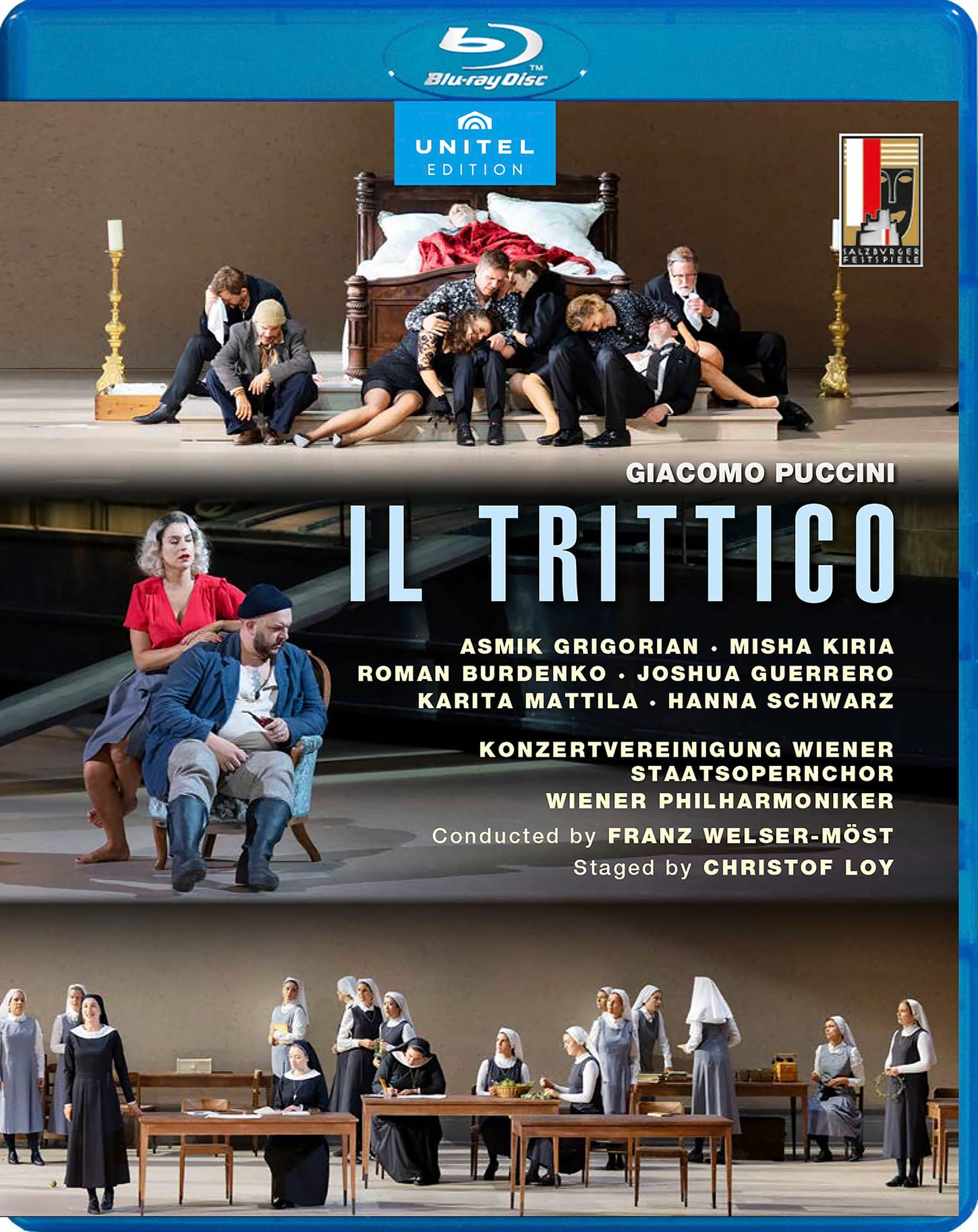

Recently, we covered two operas extracted from Puccini’s Il trittico: at ENO: Suor Angelica (review here) and, on DVD from Florence, Il tabarro (review here). So it is only right we consider the full deal (albeit in an order that is not the accepted one: this is Gioanni Schicchi, Il Tabarro, Suor Angelica).

All three are great operas. Gianni Schicchi is the comedy, and I have covered it previously in a webcast from Piacenza, Italy. And we have come across director Chris Loy before several times: his Verdi Forza at Covent Garden (review here), his phenomenally interesting re-imagining of Tosca at ENO (review here), his remarkable staged Winterreise from Basel, (review here) and finally, his gloriously escapist film Springtime in Amsterdam (review here).

On he basis of that list it is difficult to pin Loy down to any particulardirectorial current. Here in Vienna, he sets the operas minimally. Schicchi is set in a grey/brown room, sparsely populated with chairs (and a fridge/freezer in the corner) and of course a bed. Dress is modern, and the stage becomes one very large room (stage designer Étinne Pluss). The time is

One often creates strengths is the exactitude of the orchestra (the Vienna Philharmonic, so clear-cut attack was never going to be an issue); they allow themselves some rawness at verismo climaxes. We hear this in Gianni Schicchi, too, where the VPO manages to sound really quite raw at times.

Here’s an excerpt from the opera. The setting is around the 1930s or 1940s, I think:

The real highlight of Schicchi, and of the entire set, s Asmik Grigorian: Lauretta in Schicchi, Giorgeta in Tabarro and the titular character in Suor Angelica. She magnetises teh audience (whether in the opera house or at home) and provides one often finest of “O mio babbino caro’s (translated here, with its German subtitles, as “O main liebster Papa”):

Contrasting that is Welser-Möst’s command of his forces so that the fast ensemble moments (and there are quite a few of them) carry ll the excitement the score surely demands. A brilliant, involving experience.

Misha Kiria is a fine Schicchi, Enkelejda Shkosa a fine Zita. Fabulous. Of course the staging is somewhat at odds with the froth that pours for Puccini’s score … musically, though, zero complaints.

Next up is Il tabarro (The Cloak). Michele, a barge owner, is played by Roman Burdenko; Grigorian is Giorgietta, the longboatman Luig is Joshua Guerrero. t is amazing how Grigorian’s voice and demeanour move so convincingly and fully from one opera to the next.

Here, we see a boat on stage and the lighting (Fabrice Kebour) is completely different, dark, a place of base urges. t has to be said the VPO’s imitation of a hurdy-gurdy is remarkable, haunting, Modernist eve. The two Mal principals stand as opposites: the dead Michele and the exciting lover Luigi (Burdenko and Guerrero respectively). Welser-Mös’s achievement here is to move from an emphasis on an effervescent foreground (Schicchi) to the longer-range harmonic machinations of Tabarro. Here’s Grigorian’s “È ben altro il mio sogno”:

As La Frugola, Enkelejda Shkosa is in commanding form. There’s no doubting Guerrero’s virile tenor, either, but in the end it is Burdenko’s Michele that is grigorian’s dramaic equal. he end is overwhelming.

Both Grigorian and Shkosa return in Syuor Angelca (as Angelca and a Badessa); plus there is another superstar, Karita Mattila, as La Zia Principessa (Martina Russomano. who was a charming “amante” in Tabarro, returns as Suor Osmina).

The austerity of the setting suits the story of course – we return to the bare set and chairs of Schicchi, but minus the bed. The same sense of an ensemble cast working so well together informs Angelica, too, albeit to a very different end. Matilla here, as the aunt, casts not a spell but a chill, while Welser-Möst has his players relish the ambiguous harmonies that underpin her line.The role is lower the one might associate with Matila, but it matters not one jot. he understated, quiet dynamic of the scene between Mattila and Grigorian is utterly compelling.

There is some excellent camerawork throughout, angles we just wouldn’t see in the theatre, but which illuminate either via close-up or placement (the emotional distance between Michele and Giorgetta onto sofa together, but miles apart emotionally, in Tabarro).

The arrangement of Grigorian’s cost later on in the opera seems to reflect her tortred metal state. Ending with Suor Angelica reminds us of the Power of Puccini the tragedian. It is remarkable, too, that Grigorian has eh dramatic as well as vocal stamina for his piece, especially in its later stages.

Here’s the final scene of Suor Angelica:

This is a fascinating Trittico. The staging might not be for everyone, but Grigorian and Welser-Möst triumph.