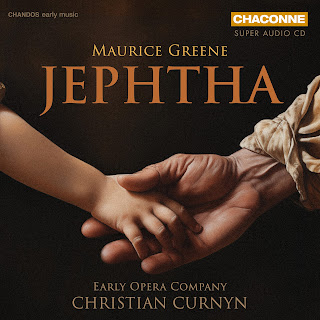

Maurice Greene: Jephtha; Andrew Staples, Mary Bevan, Michael Mofidian, Jeremy Budd, Early Opera Company, Christian Curnyn; CHANDOS

Reviewed 28 April 2025

Written well before Handel really welded oratorio in his own form of music drama, Maurice Greene’s early experiment combines graceful music with a certain static element in the drama but with some lovely moments and engaging touches

Maurice Greene is one of those composers who, though central to musical life in early 18th century London, has been relegated to the side-lines, his name popping up on the fringes of Handelian history. Eleven years younger than Handel, by the 1730s he was organist of St Paul’s Cathedral, and Organist and Composer to the Chapel Royal, he was also, from that year, nominal Professor of Music at the University of Cambridge and, from 1735, Master of the King’s Music, at which point he held all the major musical appointments in the land. As Master of the King’s Music he succeeded John Eccles and was himself succeeded by William Boyce (Greene’s pupil), whilst as organist of the Chapel Royal he succeeded William Croft.

His output is mainly in sacred music which is all the more intriguing when he moved into oratorio, at a time when Handel was not entirely committed to the new genre. The new recording from Christian Curnyn and the Early Opera Company on Chandos is Maurice Greene’s 1737 oratorio, Jephtha with Andrew Staples as Jephtha, Mary Bevan as his daughter, Michael Mofidian and Jeremy Budd as the elders.

In 1732 and 1733, Handel produced in relatively quick succession the oratorios Esther, Deborah and Athalia, none of them in the first rank of Handelian oratorio. Then he returned to opera. Not until 1739 did he create another oratorio, Saul but this time the form had settled in his mind and Saul is an undoubted masterpiece, the first of many. Maurice Greene seems to have been heartened by Handel’s example and in 1732 he produced his first, short oratorio, The Song of Deborah and Barak. He further extended his range in 1734 with the ‘dramatic pastoral’ Florimel first performed at the Bishop of Winchester’s palace in Farnham with a libretto by the Bishop’s son, John Hoadley (also a clergyman).

In 1737, Hoadly and Greene would write Jephtha, a full scale oratorio on the Biblical subject. It was premiered at a private music society, the Apollo Academy and little is known about its first performance. A libretto survives with the names of the first performers – men from the choirs of St Paul’s and the Chapel Royal, plus Isabella Lampe, wife of Frederick Lampe (Handel’s bassoonist and composer of The Dragon of Wantley) and younger sister of Handel’s soprano Cecilia Young. Only one manuscript survives, with annotations that hint at subsequent performances.

When listening to the work, it is necessary to forget the drama of Handel’s Jephtha. For a start, Hoadley’s libretto is far more static and lacks the imported elements of Greek drama that make Handel’s Jephtha so striking. There is only one named character, Jephtha, his daughter remains simply Jephtha’s daughter, and there are two elders who get significant air time too. The choruses lack the monumentality of Handel and you feel that Greene is very much the heir to composers such as Purcell. As oratorio, this work is closer to the work of composers like Carissimi than to Handel’s large-scale music drama. In fact, Carissimi’s 1648 Latin oratorio Jephte had featured in a concert of the Academy of Ancient Music in 1735, two years before Greene wrote his.

Greene does use accompanied recitatives (two in Part One and four in Part Two) and these are amongst some of the most striking dramatic moments. Though Jephtha’s daughter only has two major arias these are both substantial. Her entrance, as part of a chorus, is engaging enough but then after the cataclysm she has two seven minute long arias. The first a terrifically potent mix of touching drama and virtuosity, the second powerful indeed. Mary Bevan really has the measure of these and makes the most of her opportunities both musical and dramatic.

As Jephtha, Andrew Staples has a harder time of it. It is a lyric part, highly suitable to Staple’s voice but the role never really gives him anything meaty, his arias (of which there are a few) tend towards the engaging, by turns vigorous and touching. Staples can indeed do lyrical beauty and he manages to make his contribution cumulative, each aria building on the previous. Overall, we get a real sense of Jephtha’s moral steadfastness. We should perhaps remember that first cast, with an experienced dramatic soprano as the daughter and one of the singing men from cathedral or Chapel Royal in the title role.

As the two elders, both Michael Mofidian and Jeremy Budd make the most of what they are given. Each has an aria, with Mofidian bringing brilliant blackness to his and Budd more lyrical beauty, and the two contrast magnificently in their duet. They serve little dramatic purpose but make a very striking backdrop.

The choruses are efficient and attractive, and with the orchestra the whole forms something rather lovely. It is clear from this work and from Handel’s first three oratorios that composers were finding their way with the form. The aim here seems less about an alternative form of music drama and more about an effective presentation of the Biblical story. Greene succeeds in imbuing the story with a sort of sorrowful melancholy and there is certainly no fake rejoicing at the end.

Greene’s music is never less than engaging and there are many incidental beauties here. Overall, the work seems to sit in a hinterland somewhere between Purcell and Handel. As with Eccles’ English operas, this is something of a might have been. He never seems to have written another oratorio and he is best known for his anthems, you wonder what that first audience felt about Greene’s Jephtha. Does his silence in the oratorio genre suggest that that first audience was less than enthusiastic, or is that reading too much into it.

Maurice Greene (1696-1755) – Jephtha (1737)

Jephtha – Andrew Staples (tenor)

Jephtha’s daughter – Mary Bevan (soprano)

First Elder of Gilead – Michael Mofidian (bass)

Second Elder of Gilead – Jeremy Budd (tenor)

Soloist in duet ‘Awake each joyful Strain’ – Jessica Cale (soprano)

Early Opera Company

Christian Curnyn (conductor)

Recorded Church of St Augustine, Kilburn, London; 4 – 8 March 2024

CHANDOS CHSA 0408(2) 2CDs [40:33, 58:18]

The blog is free, but I’d be delighted if you were to show your appreciation by buying me a coffee.

Elsewhere on this blog

- More than novelty value: at Conway Hall, the Zoffany Ensemble explores substantial 19th century French works for nine instruments – concert review

- Creating a fun day out as well as broadening the mind: Jack Bazalgette on his first Cheltenham Music Festival as artistic director – interview

- From RVW’s Sancta Civitas & Bliss’ The Beatitudes to Reich’s The Desert Music & Birtwistle’s Earth Dances, plus 19 premieres: the BBC Proms 2025

- Fierce virtuosity & sheer delight: oboist

Olivier Stankiewicz, soprano Lucy Crowe, violinist Maria Włoszczowska

& friends in a captivating evening of Bach, Zelenka, Handel, Vivaldi

– concert review - Dramatic engagement: Francesco Corti directs Bach’s St John Passion with the English Concert at Wigmore Hall on Good Friday – concert review

- Searching for possibilities: composer Noah Max on his four string quartets recently recorded by the Tippett Quartet on Toccata Classics – interview

- Youthful impulse and power: Mozart’s Requiem from National Youth Choir, Sinfonia Smith Square and Nicholas Chalmers – concert review

- Looking at these modern classics anew: Britten’s Canticles at the Barbican with James Way, Natalie Burch & friends – concert review

- This production, will undoubtedly be remembered for years to come: Massenet’s Werther in Paris with Marina Viotti, Benjamin Bernheim & Marc Leroy-Calatayud conducting Les Siècles – opera review

- Compelling & magisterial: Sunwook Kim directs Chamber Orchestra of Europe from the piano in Beethoven’s 3rd & 4th piano concertos – review

- Home